The Philharmonic’s December 16 “Messiah” proved enjoyable, if not revelatory. The violins and trumpets duly impressed, but Masaaki Suzuki’s pacing seemed episodic. The four soloists all commanded baroque style — including lavish ornamentation in repeats — but were reliable and pleasing rather than striking. Sherezade Panthaki has a bright soprano so instrumental in attack that when she shades flat on some high notes, it feels exposed; her vocalism was enjoyable, but she could have brought urgency and affirmation to the resonant text. The others, all part of the LGBTQ+ community, made more verbal points. Reginald Mobley’s soft-grained, floaty countertenor soared when needed and lent dignity to “He was despised.” More quicksilver Monostatos than lyrical Tamino in sound, Leif Aruhn-Solén offered agility and musicianship, if little timbral warmth. Jonathon Adams, a Cree-Métis two-spirit baritone, showed a truly lovely and expressive instrument; they aced the quieter portions but in this large room had to work at grander moments like “The trumpet shall sound.” The very best singing came from the splendidly tuned Handel and Haydn Society Chorus.

Devoted to new chamber opera work for a decade, the valuable Prototype Festival presented an effective and at times gripping double bill of works by Irish composer Emma O’Halloran (to librettos by her uncle, gay writer/actor Mark O’Halloran) at the Ablons Art Center January 8. “Mary Motorhead” was a bleak, rock-underpinned monodrama for a prisoner, detailed with conviction and sterling diction by mezzo Naomi Louisa O’Connell. “Trade” — drawn from Mark O’Halloran’s 2011 play (and 2019’s opened-out film “Rialto” — depicts a sad but intimate encounter between a hustler and his married john. Both claim not to be gay and express contempt for “them” who are out; but both need one another. Elaine Kelly led a fine ensemble of 10 players, while onstage both classically trained Broadway baritone Marc Kudisch and ethereal tenor Kyle Bielfield gave superbly detailed, musically scrupulous and cumulatively moving performances. Tom Creed’s direction and Christopher Kuhl’s haunting lighting complete the effect.

January 12 witnessed the affecting world première in the Met Museum’s Grace Rainey Rogers Auditorium of “Songs in Flight,” directed by Kimille Howard with texts curated by Tsitsi Ella Jaji and music by Shawn Okpebholo. It ambitiously and poignantly attempts a consideration of and response to the experiences of runaway enslaved Black people, utilizing horrifically banal texts of press advertisements for their capture and return. The extraordinary banjoists and songstress Rhiannon Giddens prefaced it with a thoughtful introduction and several powerful numbers, and then joined three operatic colleagues, rich-voiced soprano Karen Slack, intense baritone Will Liverman and (again) the soaring Mobley, with Howard Watkins at the piano. From scraps, as Giddens stated, some powerful history was reclaimed and put in a musically powerful and all too achingly pertinent contemporary context.

With the Metropolitan’s many revivals, it seems aptest to underline the good achievements. At December 16’s “Magic Flute,” vocal distinction emanated chiefly from Ben Bliss (Tamino), the ever-lively Joshua Hopkins (Papageno), Lindsay Ohse (Papagena) and fine lyric soprano Joélle Harvey, who in her G minor aria and final duet with Bliss evinced the evening’s only emotional engagement. Harvey alone also spoke the dialogue with natural emphasis. A new German-language “Flute” staged by Simon McBurney premières in May, not a moment too soon.

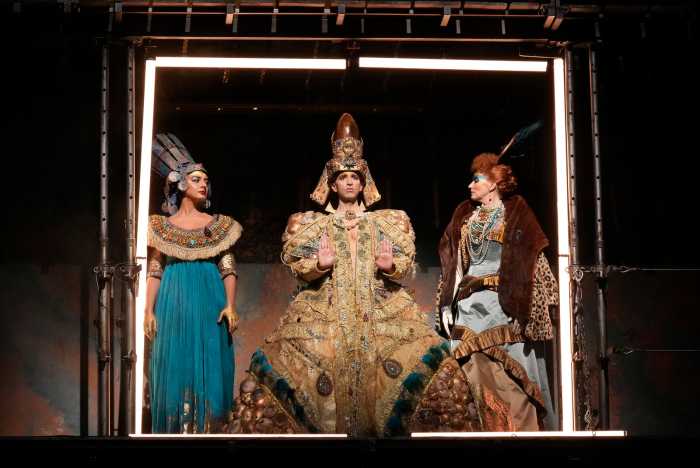

The last run of Sonja Frisell’s gargantuan, enjoyably old-fashioned 1988 “Aida” staging had been plagued with cast change chaos, but by January 3 it proved — if hardly a night of historic vocalism — musically coherent under Paolo Carignani and, well, fun. Horses, scenery applause, clueless and shirtless extras — when shall we see this all again? Verdi’s opera’s music itself can sweep one away. Michelle Bradley’s gorgeous, theater-filling voice struggled often with flatness at the top, but the potential is there. The best performance came from Olesya Petrova’s Amneris: not a ravishing timbre, but met all the vocal and dramatic challenges head on, even voicing the three “Ah, vieni” phrases compellingly softly. Alexandros Stavrakakis’s robustly voiced King deserves the casting department’s close attention.

Revival director Gina Lapinski took some, though not all, of Bartlett Sher’s stupid, counterproductive ideas out of 2012’s handsome “L’elisir d’amore” staging. Seen January 13, Donizetti’s charmer — a great first opera and also “first date” opera — worked its magic (despite awkward conducting) due to the two compelling leads, Javier Camarena and Golda Schulz. Nemorino is rather low for him and Adina needs a touch more oomph than she provides, but both are fine musicians and committed performers with lovely voices, so that Act Two especially emerges both amusing and very touching.

The next evening, the gaucheries and sheer ugliness of Michael Mayer’s “Traviata” production proved irrelevant when fronted by Ermonela Jaho’s mesmerizing Violetta — completely committed to text and action and sung with an individual timbre and a technique that, if not perfect, derives its fascination from her uncanny ability to sustain long piano lines. Some breathtaking singing— full-voiced yet elegant — also came from the new Mongolian baritone, Amartuvshin Enkhbat. These two are the genuine article. Ismael Jordi made a sexy Alfredo, with a rather oddly produced but acceptable tenor. Marco Armiliato led a strong group of comprimarios, young and old, in a highly enjoyable evening.