The works of British lesbian composer Dame Ethel Smyth (1858-1944) are undergoing a salutary revival. Smyth found more success in Germany (“Der Wald,” heard at the Met in 1903, was sadly the last opera by a woman done there for 113 years). Smyth’s strongest operas are two maritime works that surely suggested some coloration to later composers, including Vaughan Williams and Britten: “The Wreckers” (1906) and “The Boatswain’s Mate” (1916). “The Wreckers,” set in 18th century Cornwall — a remote region with evident Wagnerian associations) — has a libretto by Henry Bennet Brewster, the lone male among Smyth’s many lovers. Sea-surrounded Cornwall, beset by severe poverty, hosted “wreckers” who lured ships to their doom, stole the goods and killed any survivors. In the opera‘s community, the local pastor Pascoe is complicit in this enterprise, while his disgusted wife Thirza has found love with Mark, a local fisherman who’s abandoned his former girlfriend, the (also complicit) lighthouse keeper’s daughter Avis. Avis’s revenge against Thirza first implicates Pascoe in the fires lit to warn off ships, but Mark (the actual culprit-with-conscience) and then Thirza confess, earning the traditional punishment for treason (drowning in a cave) after the sort of Liebestod-for-two, which is familiar from so many post-“Tristan” operas, from “Andrea Chénier” to “Rusalka.”

On November 11, Houston Grand Opera Music Director Patrick Summers led a coherent reading capturing the score’s sweep; the chorus, very important in this work in ways that prefigure “Peter Grimes,” offered committed, sonorous work. Director Louisa Muller, designer Christopher Oram and skilled lighting designer Marcus Doshi captured the look and feel of a rough seaside community. Muller obtained considerable dramatic nuance from principals and choristers alike. Only the threatened final inundation proved too tame. Sasha Cooke’s beautifully sung and forcefully enacted Thirza yielded another triumph to this undervalued American mezzo. Soprano Mané Galoyan (Avis) offered a lovely, soaring top voice, good stagecraft and musico-dramatic conviction. Reginald Smith, Jr. made a bluff but powerfully expressive Pascoe. Tenor Norman Reinhardt (Mark) seemed overparted in terms of vocal format and underengaged dramatically. Jumping in for an indisposed colleague, HGO young artist Erin Wagner showed much vocal promise in the trouser mezzo role of Jack. “The Wreckers” proved worth reviving.

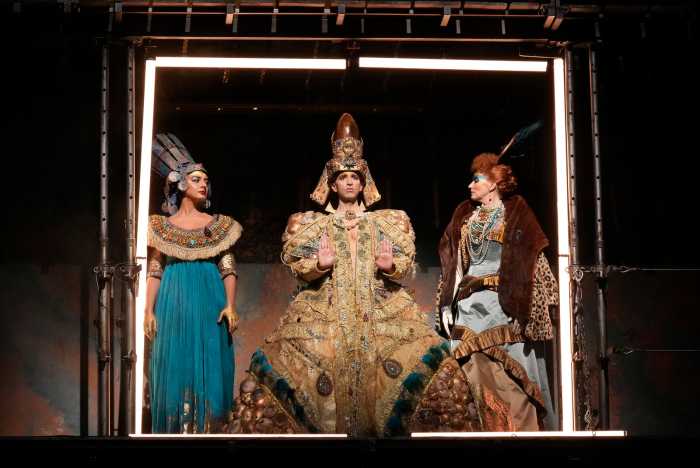

On November 13 Lyric Opera of Chicago presented Bartlett Sher’s needlessly “meta” staging of Rossini’s (in principle elegant) comedy “Le comte Ory,” his direction so aggressively set towards “acting funny” that almost nothing was funny, save for some very droll moments from Lawrence Brownlee, singing wonderfully in the lead. But the mugging and pratfalls put a damper on real comedy. The chief mugger, Kathryn Lewek unleashed her beautiful tone and confident technique with great skill, if occasionally greater skill than taste when it came to inserting high notes–not that the cheering audience complained. One hopes the Met gives her Mozart’s Constanze, a natural fit. Kayleigh Decker, was an excellent Isolier in every way–someone to watch. Young baritone Ian Rucker jumped in as Raimbaud (Ory’s wing man) and showed well-brewing talents. Zoie Reams offered a lovely voice and striking presence as Ragonde. With stylish, effervescent conducting from Enrique Mazzola, the only demerit was the Tutor of Mirco Palazzi, a needless import with unfocused tone and iffy French.

Two days before opening in the Met’s “The Hours,” out gay countertenor John Holiday, a fabulous vocalist in many genres of music, appeared at the 92nd Street Y with six young New York Philharmonic’s instrumentalists. Four string players and flautist Yoobin Son shone in music ranging from the 17th century to the present, a moody program, literally and figuratively dark-lit. Working with pianist Eric Huebner, Holiday interwove seven songs from the almost certainly gay Franz Schubert’s iconic cycle “Die schene Muellerin” into the mix. It proved frustrating, as throughout he buried his face in the score that he held up, robbing the audience of any sense of direct contact with him or with the text. (This reliance on ‘book’ has become an interpretive pandemic among younger singers.) Plus he and Huebner rushed the tempi of many songs, so that the words felt skated over. Technically, the one flaw in Holiday’s beautiful vocalism was consistently raising the volume, sometimes to the point of hardening the tone, in ascending intervals. But in the unrushed numbers like “Des Baches Wiegenlied,” one could sense that he clearly has it in him to do these songs full justice; one hopes he finds the time in his busy schedule to do so.

Unlike Alice Tully Hall, the Y has not abandoned vocal recitals, which suit smaller halls so well. Next up, on December 1, was the gifted J’Nai Bridges in a pleasing program the theme of which she described as “Finding Your Strength.” Bridges’ rich mezzo, a highlight of the Met’s initial “Akhnaten” in 2019, may best be experienced riding over an orchestra, but she’s an entrancing presence and seemed–once again, with some reliance on a music stand, but with a world première involving a string quartet that’s understandable–invested and communicative. (Still, the Y should always provide full texts of songs performed; Bridges’s diction is quite clear but her voice’s exciting vibrato obscured some more pressured passages.) Special highlights included the emotional opening “Every Time I feel the Spirit” and Manuel de Falla’s “Seven Popular Songs.” Bridges offered winning, unhackneyed interpretations, though her voice, which takes a while to “speak” suited the slower songs best. “Asturiana,” the heart of the cycle, was beautifully paced and phrased. She also essayed with considerable skill John Carter’s Cantata, a 1959 arrangement of four Spirituals premièred by Leontyne Price. It’s an intriguing setting that puts a distinctive and complex mid-20th century harmonic spin on material that might be best served by greater simplicity; Bridges gave particular resonance to “Sometimes I feel like Motherless Child”.

Pianist Mark Markham was less than precise in the Spirituals but rose to the de Falla cycle with polish. The fine Catalyst Quartet joined the mezzo for the moving, well-structured world première four song cycle “Airs for Mother,” with words and music by Peruvian-born gay composer Jimmy López Bellido: clearly a work of mourning for his mother, its second person addressee. Bridges handled its demands–including some judicious melisma and parlando effects–well, and (at least usually) meshed dynamically with the string players, often using pizzicato technique. This worthwhile cycle adds to the short list of compelling works (Schoenberg, Barber) for vocalist and quartet. Bridges left the happy audience with Carmen’s “Habañera,” ending a nice evening.

December 8 the Met hosted a “Rigoletto” with six strong principals — no common occurrence. (In small roles, however, only Eve Gigliotti’s fully drawn Giovanna and chorus bass Yohan Yi’s Guard sounded impressive.)

Veteran American baritone Michael Chioldi again won cheers for his detailed, sensitively sung Rigoletto. The company is lucky to have recourse to such a satisfying alternate to Quinn Kelsey in the role. Lisette Oropesa made a justly applauded seasonal return, her voice filling the house with exciting and individual tone, wisely deployed.

New to the company this year, star French tenor Benjamin Bernheim proved an elegant, understated Duke of Mantua, to my mind far more interesting than the usual macho caricatures. His refinement of phrasing and dynamics will be welcome when he returned in his native French repertory. These three all clearly listened and reacted to one another’s text, now matter how distracting Sher’s pointlessly revolving and upstaging production got. Also new hereabouts, Aigul Akhmetshina (Maddalena) showed a fine, tangy mezzo. Bass John Relyea continued his resurgence with an inkily solid Sparfucile. Bass-baritone Joseph Barron handled Monterone’s shorter, tricky music with generous aplomb in his biggest Met gig to date. Speranza Scappucci conducted unevenly, but this was a memorable night.