One of the developments coming out of last week’s International AIDS Conference in Barcelona that has attracted widespread attention, from Rex Wockner writing in this newspaper to reports in The New York Times, was the return of boisterous, late ‘80s style protests to the battle against the epidemic.

Vaguely implicit in this reporting is the suggestion that somehow this amounts to a revival of the “good old days” of activism. To the extent that is true, I am afraid that these reports may widely be dismissed by most gay men in New York.

The simple fact of the matter is that the level of engagement among New York gay men on the issue of AIDS isn’t anywhere close to where it was a dozen years ago, nor are the trend lines moving in that direction.

Thus, upon hearing that activists are once again mounting noisy protests, my guess is that most folks here will simply assume that they are the work of a radical fringe, perhaps not unlike what many see as the perhaps well-meaning, but ultimately out of step dissidents who now regularly show up at world economic meetings.

This conclusion I believe misses the central meaning of what took place last week in Barcelona.

Clearly, any one who jumps up on a stage in front of 15,000 delegates at an international conference to confront the United States Secretary of Health and Human Services has a flair for the dramatic. But the truly dramatic fact of Tommy Thompson’s misfired speech in Barcelona was that the protest organized against him was planned not only by ACT UP, but also by Gay Men’s Health Crisis. And the noise that kept him from speaking was not that made by a crowd that The New York Times estimated to be several dozen, but by the impatience and anger of the delegates themselves.

The reaction against Thompson and against the Spanish health minister was not the work of a small group of outsiders; it was a revolt of the insiders. AIDS advocates who for years have increasingly sat at the table, and in the view of some of their critics been too often co-opted there, were sending a message to their Spanish hosts (who were inept at opening up their country to the full roster of activists who wished to attend) but more importantly to the Republican administration in the United States that enough was enough.

The Bush administration was harshly criticized not only for what many activists viewed as an inadequate commitment to fighting the global AIDS crisis, but also for failures at home––insufficient treatment funds for state AIDS Drug Assistance Programs (ADAPs), failure to fund needle exchange programs proven to reduce HIV transmissions, and, most pointedly, for emphasizing the illusion of abstinence-only sex education at the expense of “science-based prevention efforts.”

Bush isn’t receiving a lot of criticism at home these days (though Enron-Harken-Halliburton is beginning to change that), so the role of GMHC and other blue chip names in the U.S. AIDS establishment in formulating the challenge to the President is the real significance of angry activism’s resurgence in Barcelona.

As one letter to the editor in this issue points out, however, the rebuke of Bush administration policy was only half the story in Barcelona.

The other half is the inside job we have to do as gay men here in the U.S.

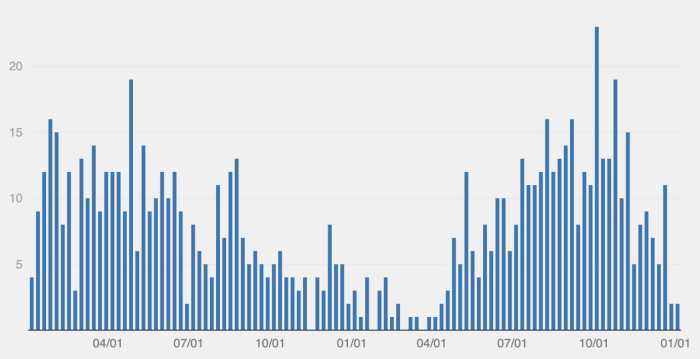

For several years now, in study after study, we’ve witnessed disconcerting evidence that unsafe sex is on the upswing among gay and bi men in the U.S. The data comes from studies of sexual practices, from indicators of new HIV infections, from public health reports about surging rates of syphilis and other STDs. We’ve seen the links between alcohol and drug abuse and unsafe sex. And we’ve known for some time that the problem is particularly serious among young men of color, especially African Americans, and to a lesser, though still alarming, extent Latinos.

In tandem with the growing profile of HIV disease in America as an affliction of communities of color, it has been tempting to conclude that the problem is only in those communities. According to that line of thinking, prevention has largely been a success in the gay community overall (read white). Communities of color are in rough shape, this theory goes, because as a nation we have failed to do a proper job of education there, because prevention efforts there have not taken on sufficient urgency.

There can be no doubt that we are failing communities of color in terms of prevention, and the hastened pace of demands for more targeted funds aimed at inner city minority neighborhoods are fully justified.

But the queer community better stop cold in its tracks if it believes that our prevention problems are simply a matter of better targeting the black and brown among us.

On the heels of so many studies already pointing to a more general problem, a new report from the Centers for Disease Control must certainly give pause. Among 6,000 young gay and bi men, 29 and younger, more than three quarters of those who tested positive for HIV were unaware that they were infected. Most in fact thought they were negative.

There is a racial and ethnic component to the numbers. Among African Americans, 90 percent were unaware of their status. The corresponding numbers for Latinos and white were 70 and 60 percent, respectively.

None of these numbers provides any comfort to any group who fancies itself immune to what can only be judged a critical breakdown, both in prevention and in our commitment as a community to HIV testing. Clearly, we are failing the youngest members of our community.

More startling is the fact that our failure is even befuddling the experts.

AIDS Action is a Washington-based group that represents the interests and concerns of several thousand HIV advocacy and service groups on Capitol Hill. Wockner quotes the group’s public policy director, Scott Brawley, saying, “Prevention messages are not working… My honest response, as a gay man, is that things are going to have to get worse again before they''ll ever get better. Resistant HIV, an explosion of HIV, something that may go wrong with the medications.”

Score Brawley some points for honesty, but this is not a comforting message.

Once before, gay men got exercised about AIDS in large measure because of a widespread view that the experts––at that time the medical establishment generally––were failing them.

Despite their best efforts, the experts may be failing again. This is not a matter of assigning blame. It’s a matter of taking responsibility for our lives.