Discharged vets voice vindication even as some West Point cadets remain cautious

It was a signal gay moment celebrated in New York’s most historic gay venue –– the end of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell (DADT), the 1993 Clinton-era gay military policy, in the Stonewall Inn, the iconic Christopher Street bar that sparked the modern gay rights movement more 40 years ago.

By 8 p.m. on September 20 –– just before City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, pulling Queens Councilman Jimmy Van Bramer on stage with her, gave a short speech in honor of the occasion –– the Inn had perhaps 120 patrons, some spilling outside for cigarettes. Maybe a third were military, including West Point cadets, former military, or service members’ family, but the clues were subtle –– buzz cuts, a woman wearing her partner’s fatigue jacket, and that certain demeanor that no civilian can easily imitate.

The event was sponsored by the Servicemembers Legal Defense Network (SLDN), a group that for years pushed for DADT’s repeal while providing aid to soldiers facing discharge or trying to avoid it.

Brenda Sue Fulton graduated from West Point in 1980, the first class with female students. She said that about eight of 62 women graduating with her were lesbians, explaining, “We’re in our 50s now, you know. We’ve remained in touch.”

Fulton served in the Army for five years in the Signal Corps based in Germany near Stuttgart as a platoon leader, staff officer, and company commander. When asked her feelings about DADT’s repeal, she was at first speechless, and then suddenly said, “I can’t even describe the feeling. I tell all my folks to answer that question and I can’t answer it myself.”

Eventually she responded, “There’s a tremendous feeling of exhilaration, but you know, to me it feels less like a party and more like a moment to honor and remember the people who worked so hard to make this happen.”

She added, “Tomorrow, our active service people will be back to work and they will be as professional as they have always been, but they will do so no longer having this millstone around their neck.”

Fulton, 52, is communications director for Knights Out, the West Point LGBT alumni group, and for OutServe, the active duty LGBT military organization. She left the service in 1986.

In July of this year, President Barack Obama appointed her to the West Point Board of Visitors. This is a drastic change from when she had been investigated with the possibility of dishonorable discharge for being a lesbian, a period she called “the lowest point of my life.”

These things won’t happen again, Fulton explained, saying “most of the people in the military are under 25. They know they have been in the showers with LGBT people. The only thing those folks care about is what’s important –– once they have been fired on, once they have been in close range, it doesn’t matter who is waiting for their buddies at home as long as they know they’ve got their back.”

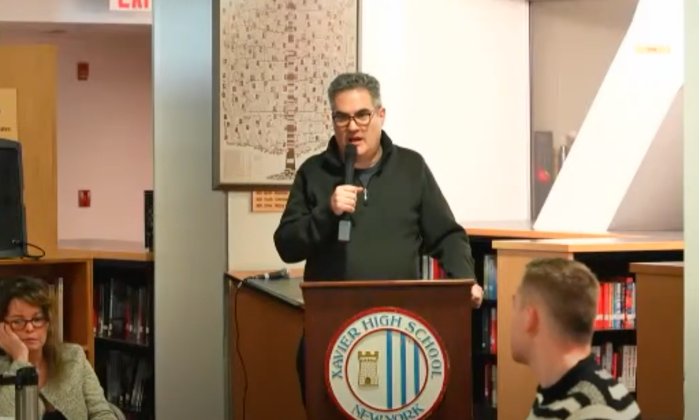

Two nights earlier, a group of about 20 LGBT veterans and their friends and supporters gathered for a repeal celebration at Manhattan's LGBT Community Center hosted by the New York and New Jersey chapters of American Veterans For Equal Rights (AVER), local groups that have also long been in the fight against DADT. After a presentation of colors by the New Jersey chapter, several veterans –– including Anu Bhagwati, executive director of Servicewomen's Action Network, and Phillip Zimmerman, a discharged Navy Arab linguist who wrote a memoir, “For the Convenience of the Government” –– addressed the group.

At the Stonewall, young, recent military service members discussed problems that persisted as they waited anxiously for DADT’s repeal.

Anthony Grecco, 22, from Connecticut, who achieved the rank of private second class in the Army, was discharged last year.

“A bunk buddy had gone through my journal and confronted me with what he found in there,” he said, adding that rather than wait for the information to be used against him, “I took it upon myself to come out to my superiors. From that day until discharge took about seven weeks.”

During the process, the Army made him see a social worker. Grecco said the experience gave him a “feeling like you weren’t good enough. But I got through the pain and the anger.”

Now that DADT has been lifted, he is reenlisting.

“I am so excited,” he said. “I have been waiting for this since July, getting the paperwork in order. I want to get in there and show them what I can be.”

For young gay men and lesbians thinking of joining the military now, Grecco said, “All I can say is, show them what you’re made of. Set the standard and show them you are a first class citizen.”

Another young veteran discharged under DADT was 20-year-old Brooklynite Yendy Rivera, who was a private first class in the Marines, thrown out in 2009. She said the repeal “is great. I am so thankful some of the people here were able to make this happen.”

Rivera has already reapplied, this time for the Army, saying, “October 1. I filed my papers already.”

She pointed that during the DADT debate, the role of women was often overlooked.

“Women are more scrutinized, so anything you do, it’s a reason for them to look at you, to give you problems,” Rivera said.

Rob Smith, 29 years old, from Akron, Ohio, a former specialist in the Army’s 4th Infantry Division, feels the DADT repeal will broaden the LGBT rights landscape. While he said that he was not out during his military career, the repeal “is all about showing people out there that want to keep us down, that want to oppress us, that these voices will not be silenced.”

Standing outside of the Stonewall Inn, he said, “It feels amazing. I feel relieved. This is a signal to see we can fight and we can win.”

Dan Hendrick, 40, Van Bramer’s partner, was discharged from the Navy in 1992, before the DADT law went into effect. He was a petty officer and a Russian translator –– “which shows how long ago it was,” he said –– with the title of cryptologist technical interpreter.

“It was tough,” he recalled. “One day I had top security clearance and the next day I didn’t. I went from a green security badge to a red one. I felt like Hester Prynne,” the character in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “The Scarlet Letter” ostracized for her adultery.

For younger people in the military today, Hendrick said, “it’s an historical milestone, that’s the big thing. But the coolest thing is the personal difference it makes today.”

He gave the example of a Facebook friend who updated her relationship status “for all the world to see” that her girlfriend is in the military.

“She couldn’t do that before,” Hendrick said, adding, “The little thing is the sea change.”

Still, according to Ben Brooks, a member of SLDN’s board, repealing DADT “is a first step. There is still much work to do. There are gender parity issues, like no alternate shower systems. Are we to be treated with equal pay and benefits?”

Opponents of repeal often threw up showers as a scare tactic in the debate, and SLDN and other advocates of open service consistently emphasized that the issue was a red herring and that no change in procedures was necessary.

Brooks, who did not serve in the military, added “The real test will be if you can bring your partner to the military ball.”

Indeed, as much as the event was a cause for celebration, it also revealed how far the military still has to go. In spite of the constant use of the phrase LGBT –– for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender –– by speakers and interviewees, a moment of silence served as a reminder that transgender service members were not included in the repeal.

Retired Sergeant Denny Meyer, president of AVER's New York chapter, reminded attendees at that group's September 18 event that because the Defense of Marriage Act denies gay and lesbian soldiers equal partner benefits, “on the first day of freedom, equality will still be denied.” He also mentioned the continued discrimination against transgender service members.

“After celebrating,” Meyer said, “it's back to 'out of the bars and into the streets,' back to negotiating and demanding. We're done with waiting. We're not going to wait another 50 years for full equality.”

A new law also cannot take away the fear that many young people still have. At one point during the Stonewall Inn event, like a protective mother, Fulton came to warn this journalist that a group of West Point cadets speaking with Quinn did not want their photographs taken for publication. An off-the-record conversation with one cadet revealed his joy at the day but also the stifling fear he still lives with of coming out to his classmates.