A quarter of a century before Oscar Wilde was sent to Reading Gaol for “the love that dare not speak its name,” the trial of two young, 20-something cross-dressing lads whom the London press dubbed the “Funny He-She Ladies” created a media firestorm.

A quarter of a century before Oscar Wilde was sent to Reading Gaol for “the love that dare not speak its name,” the trial of two young, 20-something cross-dressing lads whom the London press dubbed the “Funny He-She Ladies” created a media firestorm.

Ernest Boulton, 23, aka Stella, and Frederick Park, 27, aka Fanny, were arrested in full drag in 1870 at the Strand Theater, a popular venue for finding sexual companionship, and charged with “conspiracy to solicit, induce, procure and endeavour to persuade persons unknown to commit buggery” — a vague, Orwellian thought-crime.

Now Boulton and Park have been brought to life again in a riveting new book published last week in London by the venerable publishing house of Faber and Faber. “Fanny and Stella: The Young Men Who Shocked Victorian England” is the work of the award-winning journalist Neil McKenna, who has written for the Guardian, the Independent, the Observer, and the New Statesman. He has also contributed extensively to the queer press since the birth, in the early 1970s, of the modern British gay liberation movement, in which he was an active participant.

Neil McKenna probes the persecution, prosecution of two transgressive Victorian cross-dressers

The author of two important books on AIDS and men who have sex with men in the developing world, McKenna is best known for his must-read, eye-opening revisionist biography, “The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde,” published to critical acclaim on both sides of the Atlantic (see my August 2005 review, “Wilder Than We Knew”).

With “Fanny and Stella,” McKenna has lifted the veil on the extensive homosexual subculture that existed in London at a time when Wilde was still a schoolboy.

Fanny (standing) and Stella (front) with Lord Arthur Pelham-Clinton. | FABER & FABER

Until 1861, just nine years before the arrest of Boulton and Park, buggery had carried the death penalty, and afterward it remained punishable by a prison sentence of penal servitude at hard labor for life.

McKenna demonstrates how, as a reaction to the changing culture and morals that accompanied the industrial revolution, the purveyors of bourgeois Victorian values seized upon the sodomites as the scapegoat for the decline of family values, much as today’s American Taliban on the religious right continue their homophobic crusades.

Thus, the “conspiracy” indictment of Boulton and Park “conjured up an image of a vast, ever-spreading sodomitical spider’s web with Fanny and Stella at its dark heart, controlling and directing, combining and confederating, to entrap and ensnare any and all men.”

McKenna writes, “The arrest of ‘the Young Men Personating Women,’ ‘the Hermaphroditic Gang,’ ‘the Funny He-She Ladies,’ as they were called variously by the newspapers, had caused an unparalleled sensation. Every aspect of Fanny and Stella’s lives — their arrest, their appearance, their clothes, their backgrounds — had been lovingly and lasciviously dilated upon and speculated over and, where facts were in short supply, cheerfully invented.”

The Daily Telegraph, then as now the favorite paper of the conservative middle classes, proclaimed: “It is suspected that there are others, besides those in custody, who have for some time past been personating females in London. In fact it is stated that an association exists which numbers nearly thirty of these foolish young men.”

The trial of Boulton and Park made them household names, and they were celebrated and ridiculed in popular music hall songs and widely published limericks, like this one:

There was an old person of Sark Who buggered a pig in the dark. The swine in surprise Murmured ‘God bless your eyes, Do you take me for Boulton and Park?’

“Almost every day, “ McKenna tells us, “the net seemed to widen and another young man — and sometimes more than one — was implicated.” A “steady stream of men and women from all stations and conditions of life” called in person at the Bow Street Police Station to denounce those suspected of the “crime against nature.”

Boulton and Park were both from respectable, middle class families — indeed, Park’s father was a well-known and revered judge. The two youths had known from childhood that they were different from other boys and had for some time been dressing up and performing amateur theatricals for their families and friends.

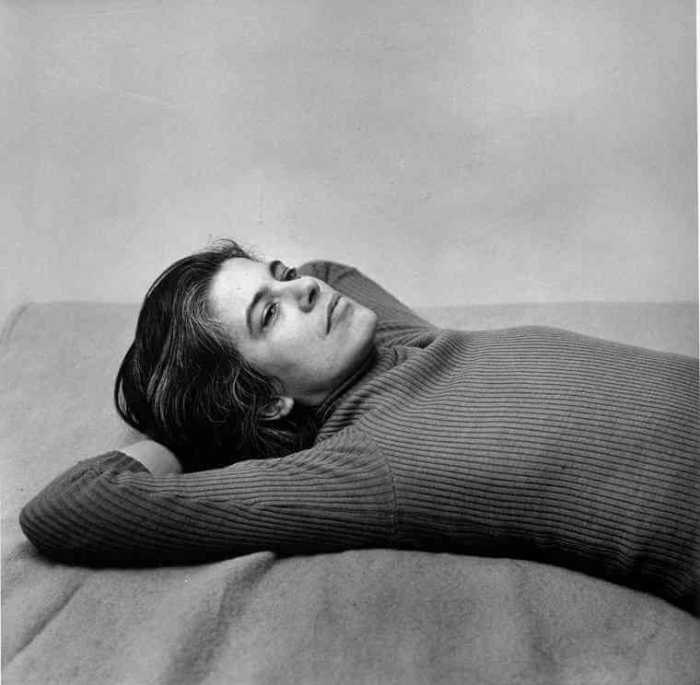

Frederick Park, aka Fanny. | FABER & FABER

Cross-dressing in and of itself was not illegal at the time. In fact, men playing women’s parts were staples of the burlesques that packed audiences into the theaters and music halls for the entertainment of the general public. Fanny and Stella had enjoyed some success themselves on the stage, with the younger, prettier Stella, who was possessed of a beautiful soprano singing voice, making a convincing female ingénue, while the plainer Fanny took roles as a dowager.

McKenna does a masterful job of recreating the lives of Fanny and Stella, who declared themselves “sisters” and lived together. When Stella began a liaison with Lord Arthur Clinton, a younger son of the duke of Norfolk and a member of Parliament, she had visiting cards printed with “Lady Arthur Clinton” inscribed upon them, and Clinton referred to Fanny as “my sister-in-law.” Clinton also had sexual trysts with Fanny, and the trio became a menage-a-trois who shared lodgings and life.

London was rife at that time with male prostitutes, although those who plied their trade in drag were in a distinct minority. But Stella had already been arrested at age 18 when, cruising for customers in the notorious Haymarket red light district, she had been set upon in a near riot by a crowd of female prostitutes who accused the convincing cross-dresser of stealing their customers.

According to the medical authorities of the day, the signs of sodomy were easily detectable. A wearing away of the rugae around the anus, making it resemble the female labia. Elongation of the penis, caused by the “traction” of sodomy. And dilation. Dilation was the biggie. The way one tested for it was by the insertion of a professional finger. Repeatedly. If the sphincter failed to show enough resistance to the learned finger-fucking, then you were dealing with a sodomite. Medicine at the time also denounced masturbation as the cause of a variety of human ills as well as for leading to sodomy.

But when Fanny and Stella were examined by a team of six doctors, only the police surgeon found evidence of sodomy, while the other medical men averred to have found none.

That is one reason why the cross-dressing duo were charged with “conspiracy” rather than buggery. But at their trial, the police surgeon was shown to have lied to the court on several occasions, while he and other prosecution witnesses, including policemen, were found to have been paid by the Treasury for their testimony.

As the charge of conspiracy melted away under the cross-examination by Fanny and Stella’s able defense attorney, “a new and very different conspiracy was emerging from the shadows. The steady stream of damaging revelations and admissions from other prosecution witnesses, taken together with [police surgeon] Dr. Paul’s transparent lies, strongly suggested that the police, the politicians, and the powers that be in the Treasury had conspired together in preparing the arrest and prosecution of Fanny and Stella.”

Moreover, their paramour and purported co-conspirator, Lord Arthur Clinton — whose godfather was Prime Minister William Gladstone — had disappeared and was thought to have fled the country before the trial.

In the end, the jury took less than an hour to find Fanny and Stella “not guilty.”

After the trial, Ernest Boulton, aka Stella, changed his last name to Byne, and with his brother Gerald as his onstage partner began performing comedies all over England. The duo moved to New York in 1874 where, taken up by one of the city’s most flamboyant and shrewdest agents and managers, Stella found success in its theaters.

The New York Clipper, a popular daily, breathlessly confided to its readers, “The gentlemen who sat next to us discussed in audible tones the merits of Ernest Byne, believing him to be a woman. After enjoying their conversation, we took the liberty of informing them of the sex of the supposed lady, and handed them a programme to substantiate it, whereupon they were completely astonished and confused.”

Fanny, who also moved to America, where she lived as a woman, died in 1881, probably of syphilis, and was buried in Rochester, New York.

Meanwhile, by the early 1880s, Stella and her brother had returned to England and continued performing, with Ernest always in drag, for the next 22 years.

“Cecil Graham,” the false name given by Stella on the night she was arrested, “reappeared in 1892 as the name of a character in Oscar Wilde’s first society comedy, “Lady Windermere’s Fan.”

Like his investigative Wilde biography, which broke new ground in unraveling the blackmail of a closeted prime minister by the marquis of Queensbury that was behind the persecution of Wilde, Neil McKenna once again shows himself adept at meticulous research. He delivers a brilliant dissection of the plotting by authorities that led to the trial of Fanny and Stella.

With his polished sense of narrative, McKenna’s new book is a page-turner, rendered in felicitous, witty prose that makes the tragicomic lives of the two cross-dressers an unforgettable tale. In telling it, he provides a panoramic picture of a stratum of underworld queer English life in pre-Wilde days that is an important contribution to gay historiography.

It is to be ardently hoped that “Fanny and Stella” quickly finds an American publisher, as this fascinating account richly merits a place on your bookshelf.

Excerpts from “Fanny and Stella” and a photo gallery of the two cross-dressers can be found on author Neil McKenna’s website at neilmckennawriter.com. In the US, the book is available from Amazon or may be ordered directly from Faber and Faber at faber.co.uk.

FANNY AND STELLA: THE YOUNG MEN WHO SHOCKED VICTORIAN ENGLAND | By Neil McKenna | Faber & Faber, London | £12.99 | 482 pages