The New York Philharmonic’s US staged premiere of Gerald Barry’s musical setting of Oscar Wilde’s “The Importance of Being Earnest.” | STEPHEN CUMMISKEY

The New York Philharmonic’s “NY Phil Biennial” will be presenting music of all kinds throughout the city through June 11 (nyphil.org/biennial). The operatic contribution was Gerald Barry’s musical setting of Oscar Wilde’s light comedy masterpiece “The Importance of Being Earnest,” which received its US staged premiere June 2-4 in a co-presentation with Royal Opera at Lincoln Center’s Rose Theater.

Paul Kilby’s program notes for the production hint at the folly of such an enterprise: “There is no sense in which ‘The Importance of Being Earnest’ needs to be an opera… that works better in a medium other than the one in which it originated.”

I am familiar with the play having played Algernon in a high school production and seeing it twice performed professionally. Wilde’s farce is all style sabotaging substance. The characters live on an exquisitely superficial plane of beautiful manners and elegant language that camouflage total absurdity, subversive social commentary, and perverse thinking. There are no emotional depths here that music can expand upon or reveal hidden layers within.

“NY Phil Biennial” proves “The Importance of Being Earnest” ought not be an opera

While Wilde smashed conventions with the sound of a spoon clinking in a china teacup, Barry smashes plates on the floor. The music is all loud, congested Schoenberg serialism — a wall of noise devoid of lightness or wit. The only time the orchestra is funny is when both Gwendolyn and Cecily react with revulsion at the real names of their fiancés — whom they both know as Ernest — and the orchestra erupts into shattering “Wozzeck” chords. Both Lady Bracknell and Miss Prism break into impromptu versions of a Schiller poem (that Beethoven used in his Ninth Symphony “Ode to Joy”) for little or no reason.

Cecily and Gwendolyn conduct their tea table catfight standing facing the audience on opposite sides of the stage declaiming through megaphones. At one point, every word of Gwendolyn’s is punctuated by a percussionist smashing china plates on the floor. In fact, all sorts of food and props are thrown on the ground, requiring considerable post-performance custodial work.

Vocal lines are largely tuneless and independent of the orchestral writing, with odd leaps into falsetto on random words or syllables for both male leads. The exception is a warped version of “Auld Lang Syne,” which recurs like a leitmotif but without dramatic resonance.

Lady Bracknell is played by a basso profundo (Alan Ewing) but not as a woman (I saw and admired Brian Bedford in the role on Broadway). Dressed in a dark business suit and conducting himself like an officious club bore, Ewing fails to be camp, frightening, or humorous — instead, merely tiresome. Gwendolyn is a smooth mezzo soprano (a coolly in-control Stephanie Marshall), while Cecily (the pretty and clearly gifted Claudia Boyle) chirps in a squeaky high coloratura range rendering text indecipherable. Contralto Hilary Summers as Miss Prism brings a touch of Hyacinth Bucket to the role and emerges with dignity intact. The drolly detached Simon Wilding doubled as household butlers Merriman and Lane.

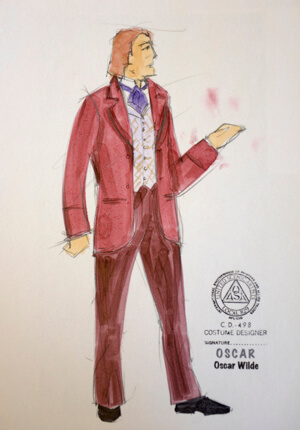

Ramin Gray set up a concert opera semi-staging on stair-like narrow black risers that accommodated both the orchestra and soloists. Clothing and manners were contemporary and casual, lacking in both style and class — Algy (baritone Benedict Nelson) looks like a Williamsburg boho hipster with beard, denim trousers, and plaid flannel shirt, and Cecily wore green short shorts. John “Ernest” Worthing (tenor Paul Curievici) sported a casual blue jacket and open necked shirt.

Conductor Ilan Volkov led members of the New York Philharmonic in a bravely uninhibited and thoroughly prepared reading of Barry’s score — to little artistic result. It is all a collection of musical and stage effects that call attention to themselves rather than support the story or characters.

In the end, it is Oscar Wilde’s witty text that endures — even though cut by a third — and entertains the audience independent of this setting. But when the surtitles steal the show, you know an opera has no reason for being.