Achebe Betty Powell, a pivotal LGBTQ leader who was a founding member of the Astraea Lesbian Foundation for Justice and the first Black woman to be co-chair of the National LGBTQ Task Force, died February 21 at New York Presbyterian Hospital in Brooklyn. She was 82. The cause of death was COVID-19.

The National LGBTQ Task Force announced Powell’s death in a press release.

During the 1970s, Powell joined the Gay Academic Union (1973-1976), where she met lesbian feminist activist Charlotte Bunch while moderating a panel discussion in 1974. The conference was covered by the New York Times, which mentioned Powell and quoted Bunch.

Powell became one of the founding members of the National LGBTQ Task Force in 1973. The year 1977 was groundbreaking for Powell: She attended the National LGBTQ Task Force’s historic White House meeting during former President Jimmy Carter’s administration and also spoke on behalf of the Lesbian Caucus at the National Women’s Conference in Houston, sponsored by the US government for the United Nations’ International Women’s Year. She was featured in the groundbreaking documentary, “Word is Out (1977).”

Powell maintained deep ties to the National LGBTQ Task Force and the Astraea Lesbian Foundation for Justice throughout her life.

Her death was a shock to her family, friends, and people she touched throughout her life.

Powell’s niece, Lisa Foster-Bryant, and nephew, David Lyon Foster, told Gay City News that while their aunt had some serious surgeries and health issues, “she bounced back to life as if she was in her 40s,” Foster-Bryant said.

“She proved herself to be very resilient to a lot of those illnesses,” Foster added.

Powell contracted COVID at a dinner party in early January. She was hospitalized January 14 and spent more than five weeks in the intensive care unit until she passed away, according to her partner of four years, Linda Fraser, and her family.

Kierra Johnson, executive director of the National LGBTQ Task Force, said Powell “was a pioneer, a visionary, an inspiration, and trailblazer in a movement that was in its early organizing days.” The Task Force, Johnson said, “was blessed to have her as a board chair and board member” and representing them “as our first Black board member” at the historic LGBTQ meeting at the White House in 1977.

For a brief time in the 1980s, Powell was managing director of Kitchen Table Press (1980-1993), a feminist women of color publisher, founded by the late Audre Lorde, Barbara Smith, and Demita Frazier.

Powell also was a founding member of Salsa Soul Sisters (1974-1993), the National Black Feminist Organization (1973-1976), and the National Coalition of Black Lesbians and Gays (1978-1990).

In her final weeks and days, Powell was surrounded by a team of friends and family in person and in spirit managed by friends Dr. Meghan Kirksey and Michelle Billies, who regularly updated the people in Powell’s life, Fraser said.

“Every aspect of Achebe’s life reflected her dedication to social justice and activism in all spheres locally, nationally, and globally,” said Fraser, overwhelmed by the tributes to Powell from around the world.

Fraser met Powell more than a quarter century ago. She worked with her agency, Betty Powell Associates, through a cultural competency training program at CUNY Hunter College for the then newly developed citywide Clinical Mental Health Case Managers Program funded by the New York State Office of Mental Health and the New York City Department of Health & Mental Hygiene.

“She was still providing that amazing training right up to the time she became ill,” Fraser said.

Longtime friend Katherine Acey said “COVID really took her and strangled her, really, in a devastating way.” Powell tapped Acey, who was honored with a joint Gay City News Impact Award in 2020, as an early board member (1983-1987) of the Astraea Lesbian Foundation for Justice. Acey served as the foundation’s first executive director (1987-2010) and remains involved in an advisory role as executive director emeritus of the Astraea Lesbian Foundation for Justice.

“This is a devastating loss, I think, to each of us personally,” Acey told Gay City News in a phone interview from Chicago, where she was with family, talking about her “spirited [and] energetic” friend.

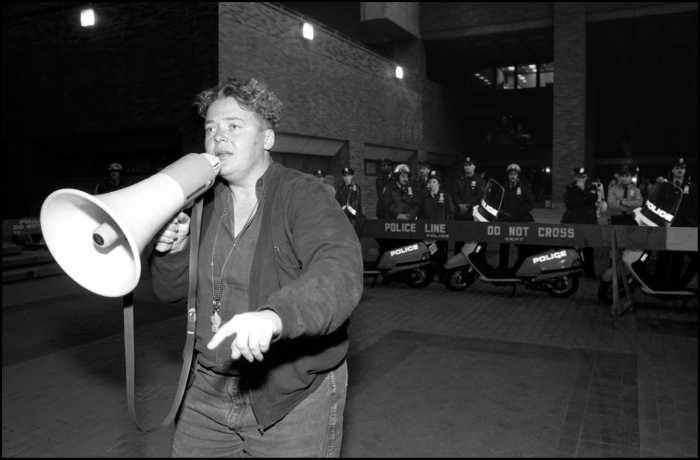

Activism

Powell was one of the first out lesbian Black activists to hold key positions in LGBTQ organizations that shaped the emerging LGBTQ movement over the next three decades into the 21st century. She dedicated her life’s work to connecting causes for social justice across diverse communities and borders.

“She was always trying to call people in, to call people into dialogue, to call people into understanding, to call people into dealing with the issues from a kind of more respectful [way],” said Bunch, Powell’s friend of nearly 50 years, in a phone interview at her winter retreat in Peru with her partner, Roxanna Carrillo.

“[It] just showed her kind of profound ability to bring people to a common point, even if they had [a] disagreement,” she said.

Lesbian author Jewelle Gomez, whom Powell mentored and befriended in the early 1980s, recalled when they first met.

“She probably was the first Black lesbian I ever met,” Gomez said in a phone interview from San Francisco. “Before that, I thought I was alone in the world.”

When Gomez expressed this to Powell, she remembered, “She just put her arms around me.”

“It made it possible for me to think about myself [as] ‘in community’ with other women,” said Gomez, who became a founding board member of the Astraea Lesbian Foundation for Justice in the early 1980s along with Acey and the late Nancy Dean and her life partner, the late Beva Eastman.

Powell’s involvement in the feminist and LGBTQ movements evolved after her divorce from her husband, Bill Powell, whom she briefly married in the 1960s. Bill Powell, who died more than a decade ago, according to friends, came out as gay a few years into their marriage. They remained friends.

Several years after their divorce, Powell came out as a lesbian.

Powell came from a family with roots in the African Methodist-Episcopal church stretching back to the times of enslavement, she told Kelly Anderson in the 2004 interview for “Voices of Feminism Oral History Project.” She briefly converted to Catholicism during her marriage, but walked away from the church in the 1970s. Later in life, she became a member of Middle Collegiate Church, in Manhattan’s East Village. The oral history interview is held digitally and in the archives in the Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College.

Powell’s career fighting for social justice began in her senior year of high school when she joined the National Conference of Christians and Jews in Miami, Florida.

Powell was a regular speaker at the Center for Women’s Global Leadership at Rutgers University founded by Bunch. She also worked with the Solidarity Network of Women Living Under Muslim Laws, which has groups in countries such as Nigeria, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Turkey.

Early life

Powell was born Betty Jean Kelly on June 14, 1940, in Miami to Rachel Harris and Army Captain and Minister Jesse Kelly. They were not married. Powell’s father joined the Army around the time Powell was born, and she said she ultimately lived in Germany with her father from the age of 14 to 17 years old.

Powell was the middle child between her oldest and youngest stepbrothers, Johnny Long and David Foster, who are deceased.

In Germany, Powell developed her love for art and culture, tennis, and the French language. Her love of music was developed in Miami and later in college at The College of St. Catherine in Saint Paul, Minnesota.

“She was a great lover of arts and culture, traditional classical, Western, and emerging African art and culture,” Bunch said. “She supported a lot of young African American musicians.”

Powell started playing tennis when she was 14 years old. Her friends told Gay City News that one of her favorite stories of her youth was that she worked briefly as a ball girl for the first African-American person to win a Grand Slam title, Althea Gibson.

Powell often went to the US Open and other tennis matches with her niece and nephews and friends, they said.

Career

Powell taught French language and culture at in New York City high schools and was a professor of linguistics and taught French at Brooklyn College.

Powell’s graduate and doctoral work also focused on urban education. Her professional diversity, inclusion, and equity and organizational development work began at Deloayza Associates in 1986. Three years later, she opened her own firm, Betty Powell Associates, in 1989, expanding upon that work.

She dedicated her life to social justice around the world and diversity, equity, and inclusion. Her friends said she was a highly sought after speaker for panels, lectures, interviews, and political events from her early days of activism until her death.

Powell is survived by her partner Linda Fraser, niece, Lisa Foster-Bryant, her nephews, David Lyon Foster and Dana Simon Foster, two grand nephews and a grandniece, friends, and the many people whose lives she touched.

Griot Circle, a New York City-based organization serving LGBTQ seniors of color, announced that there will be a service for Powell on March 11 at 1 p.m. at Middle Collegiate Church at 245 East 17th Street in Manhattan. To attend in person, RSVP by March 7 at achebeservice31123@gmail.com. The service will be streamed live at youtube.com/user/MiddleNYC.

A public memorial service is being planned for June around what would have been her 83rd birthday in New York City.