Group urging that celebration refocus on rights marches, along with the vets who led the way in 1970

That the members of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), the group that organized Manhattan’s first gay pride march 40 years ago, were sandwiched between floats from Kiehl’s, a cosmetics company, and Delta Airlines speaks volumes about how much the event has changed since 1970.

“They need money, so someone has to pay for insurance and pay for the parade, and the Kiehl’s people did give me a lot of samples,” said Rick Landman, a GLF member, who stressed that he was not speaking for the Front.

Of course, some things about the parade are unchanged. Landman said he struck up a conversation with a young man in the Kiehl’s contingent and they will be meeting again to continue that chat.

“I wouldn’t call it a date,” the 58-year-old Landman said. “He’s 27 years old.”

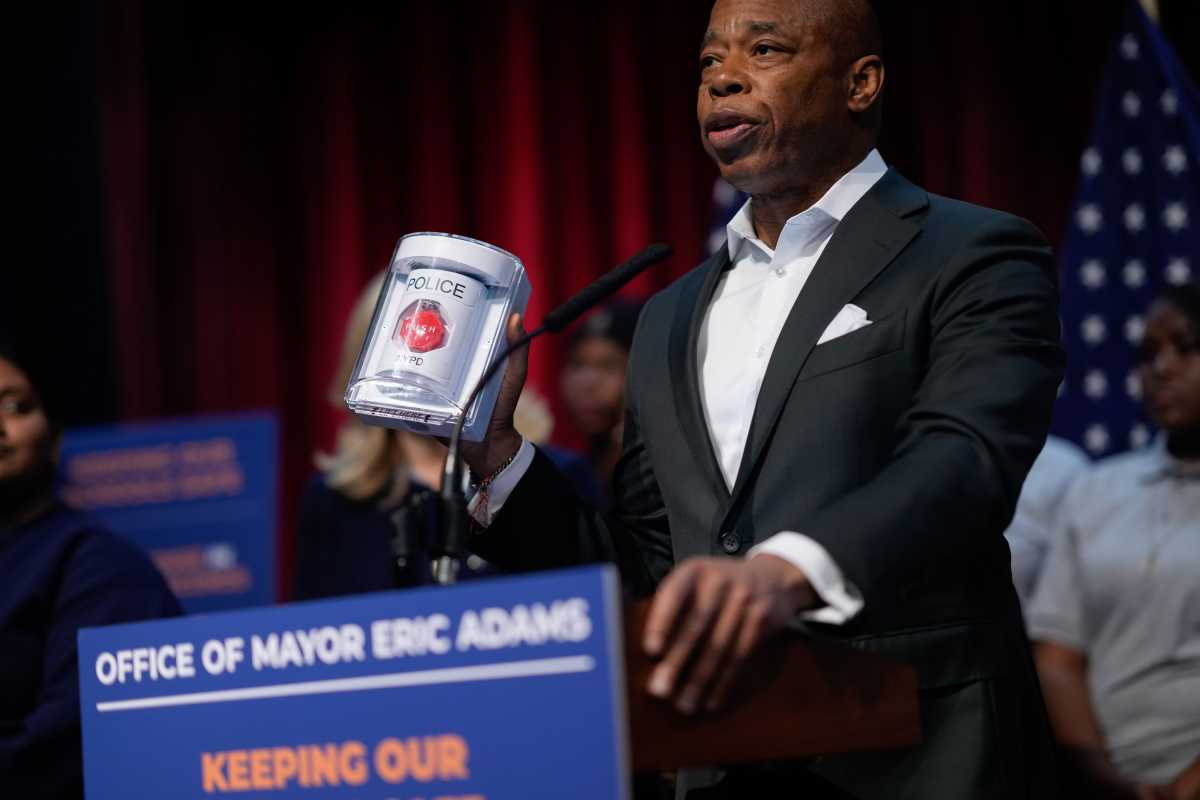

While the parade, held June 27 –– as always, the last Sunday of Pride Month –– is dominated by gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender organizations as well as religious, AIDS, and services groups that support the community, it does include commercial floats and plenty of politicians and office seekers.

This year for the first time, Heritage of Pride (HOP), the organization that produces the annual gay pride parade, rally, and dances, assigned places in the parade on a first-come, first-serve basis, which is how GLF ended up between two companies that members likely would have spurned in 1970. Many GLF members worked in far-left groups in the late 1960s before joining the Front.

As in prior years, the Sirens Motorcycle Club, usually called Dykes on Bikes when they appear in the march, led the community down Fifth Avenue — followed by the grand marshals, Judy Shepard, mother of the slain Matthew Shepard, Constance McMillen, the Mississippi high school student who sued for the right to bring her girlfriend to the prom, and Dan Choi, the openly gay Army lieutenant who is battling the military’s Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy.

Truth be told, the parade has lost an edge. It often seems like more of a celebration than a political event. That is a change that some participants addressed this year.

Take Back Pride is “a movement to put the politics back into the parade, the march back in the march,” said Jamie McGonnigal, the group’s founder, as he waited on 39th Street to step onto Fifth Avenue with roughly 40 other people.

Along the route, marchers chanted, “What do we want? Equality! When do we want it? Now!,” and exhorted the crowd that lines Fifth Avenue and nearly swamps Christopher Street to join in. The crowd participation was particularly pronounced in the West Village as the end of the parade neared.

Members of Take Back Pride also distributed leaflets reminding those on the sidewalks that an estimated one-third of homeless youth in New York City are LGBT and that in 29 states queers are not protected by law from employment discrimination.

The group was frequently cheered, though as is always the case in the pride march it is not clear if those on the sidewalk are saluting a specific group or just cheering everyone marching.

Some viewers understood Take Back Pride’s message.

“It’s about getting rid of the corporate takeover that’s about lifestyle and getting into the politics,” said Patricia Owens, as she watched with a friend.

Justin Hulse was watching with several friends and welcomed the Take Back Pride banner.

“Absolutely,” he said when asked if the parade should have a more political tone. “There needs to be legislation.”

Matt Boorady said, “I think it’s about putting politics back into pride” when asked what the Take Back Pride banner meant.

The announcer at the 23rd Street reviewing stand understood, though, in fairness, she probably had a cheat sheet.

“It is not a parade, it is not a celebration,” the announcer said as Take Back Pride went by. “It is a march, it is a protest.”

Some on the sidewalks missed Take Back Pride’s point.

“If I had to guess,” one young woman said when asked to explain the group’s banner, then she paused and added, “I don’t know.”

Others offered responses closer to the group’s mission.

“That we need to get every right that we can just like everybody else,” said a young woman.

“Equal rights for everyone,” said Charles Warren, who noted that he had traveled from Columbus, Ohio to see this year’s parade.

Robert Pinter, founder of the Campaign to Stop the False Arrests, joined Take Back Pride. Pinter was one of at least 30 gay and bisexual men who were busted by city vice cops in six porn shops in 2008. Those arrests are widely seen as false arrests in the community. Pinter’s case was dismissed, and he is suing the city.

For GLF members, this year was gratifying.

“Mark [Segal, publisher of the Philadelphia Gay News] and I were saying how nice it was that we heard people say thank you,” Landman said. “It’s always very nice each year to see that some of us are still alive and active.”