E.L. Doctorow was not convinced that “Ragtime,” his sprawling, iconic, 1975 novel about America in the early 20th Century, could be turned into a musical. To convince him — and to show that he was the man for the job — Terrence McNally wrote a 45-page treatment. Stephen Flaherty and Lynn Ahrens wrote sample songs. Doctorow was convinced.

The musical bowed on Broadway in 1998, and McNally, Flaherty, and Ahrens took home Tony awards for their efforts, and since then the show has been in constant production somewhere, including a Broadway revival in 2009.

The story of three groups of people — wealthy white people in New Rochelle, Black people in Harlem, and immigrants on the Lower East Side — begins in 1902 and over the years leading up to the First World War, these once distinct and largely isolated castes would inevitably mix, changing the country, propelling it forward, and redefining what it means to be American. The story is not without violence, bigotry, or conflict among the groups of people, but its final message is one of hope, that somehow our common humanity can transcend the darker aspects of our natures and move towards something better.

Given the current, dangerous, divisive political climate we’re enduring, there could not be a better, or more appropriate, time for a major revival of “Ragtime.” And, it’s doubtful there could be a more moving and beautiful production than the one currently filling the stage at the Vivian Beaumont.

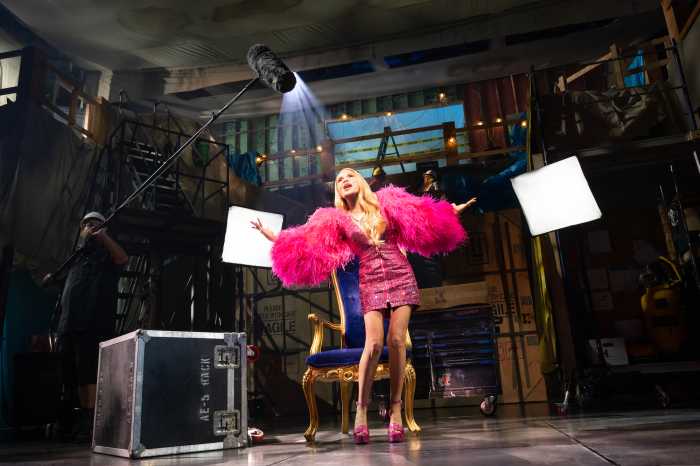

Directed by Lear DeBessonet with choreography by Ellenore Scott, and a consistently superlative cast, this magnificent “Ragtime” is arguably the definitive staging of the work. DeBessonet’s production is an ever-changing tapestry of a world in motion where people and groups interact, perhaps for the first time, as events compel them to encounter one another as fellow humans, and each, in turn, is changed. Perhaps the most remarkable (and often breathtaking) element of this is that DeBessonet has accomplished this without scenery or projections, the stock-in-trade of most grand scale musicals these days. Rather, the show is presented on a largely bare stage, though David Korins has created scenic elements that integrate with the action and convey place with precise economy. It is the people and their movement that create the astonishing theatricality, underscoring that at its heart, “Ragtime” is the story of how individuals transform a nation.

The story begins in 1902. The family (Mother, Father, Grandfather, Mother’s Younger Brother) has built a house and they are expecting that “all the family’s days would be warm and fair,” as the show’s opening says. That is not to be. Father is off to explore with Admiral Perry for a year. Mother, left alone, must begin running things independently. She finds an abandoned Black newborn baby in her garden and takes it in. The baby belongs to one Sarah, whom Mother also takes in. The baby’s father is Coalhouse Walker, Jr., a musician in Harlem — connecting two of the groups. Meanwhile, Tateh arrives in America from Latvia, where he hopes to make a better life for his daughter. He struggles as an artist trying to sell silhouettes and he discovers the American Dream is harder than he imagined. Interspersed with these fictional characters are real figures of the era — Harry Houdini, Evelyn Nesbit, Booker T. Washington, and Emma Goldman.

McNally’s book doesn’t shy away from the controversies of the times. Goldman’s championing of workers, Mother’s emergence as an independent woman, and the violent, racist story of the attack on Coalhouse and his equally violent response are galvanizing. Throughout his career, McNally never pulled back from the most direct honesty, and when white characters attack Coalhouse with the “N-word,” it hits like a cannon ball. (There were audible gasps from the audience at the performance I saw.) But it’s real, powerful, and draws one viscerally into the story.

The score by Ahrens and Flaherty is simply brilliant. With a 28-piece orchestra under the direction of James Moore, the music soars. At times operatic and at others light and comic or smaller and heartfelt, it is a musical melting pot. One can also hear the influences of the music of the era from the eponymous Ragtime to waltzes, marches, and Klezmer all reflecting the different traditions of the characters.

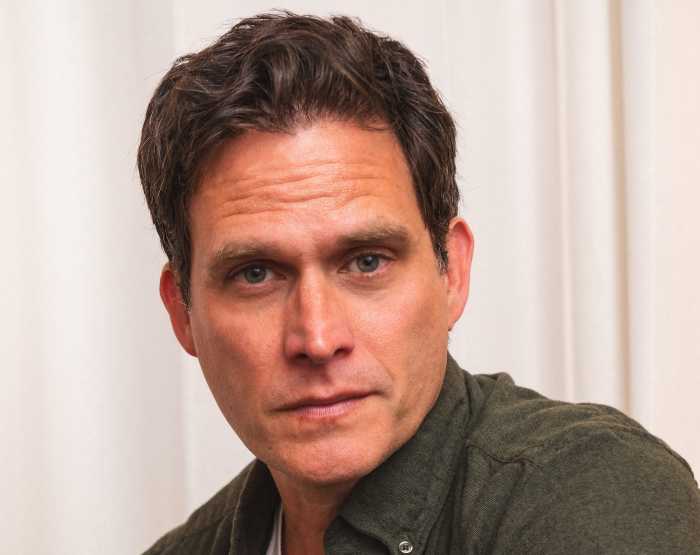

As for the extraordinary cast, let’s just start with the ensemble that provides much of the beautiful choral work and is integral to the staging. They create the sense of time and place and the backdrop for the changing world. In principal roles, Shaina Taub is forceful as Emma Goldman, bringing a youthful passion and energy to the role. Colin Donnell is Father, cutting a striking figure of rectitude and white male patriarchy but shifting as he begins to understand the new world. (The song “New Music” perfectly captures both his confusion at change and realization that his old ways may not work.)

Brandon Uranowitz as Tateh embodies the American dream, rising from a pushcart to making movies. Uranowitz plays both the complexity and comedy of the role perfectly. Nichelle Lewis plays Sarah with an abundance of simplicity but a quiet depth and a voice that touches the soul. Joshua Henry is a powerhouse as Coalhouse Walker, Jr. His rich baritone is awe-inspiring, as it has been in “Carousel” and other Broadway roles. Even with Coalhouse’s tragedy, his final number “Make The Hear You” rings out as a necessary call not to allow people to be marginalized and assert the right to their voices. Henry’s singing is masterful, and earlier in the show when he and Lewis sang “The Wheels of a Dream,” at the performance I saw, it brought the audience to its feet.

From a dramatic standpoint, Mother is the pivotal character in the show. It is through her that we most see the emotional shifts of the world. From compassion towards a baby of color, to asserting her place as a woman separate from her husband to the acknowledgement that change once done cannot be undone (“Back to Before”), to hope for the future (“Our Children”), Mother is the heart of the piece. Cassie Levy in the role is a sensation. Levy owns the stage with a delicate grace and beauty that belie her strength, even as her character persists.

It can be easy to despair in political times like these. That’s when we can turn to the arts for hope and inspiration. This is a “Ragtime” for our time, and perhaps in a challenging world can give us something to hang onto as we wait for the world to change.

“Ragtime” | The Vivian Beaumont at Lincoln Center | 150 West 65th St. | Tues, Thurs, Fri, 7 p.m.; Weds, Sat 2 p.m. & 8 p.m.; Sun 3 p.m. through January 4 | $58-$341 at Telecharge | 2 hours, 45 mins, 1 intermission