While the gay bar is not dead yet, it has been on life support ever since dating apps came out.

“The Web: The Birth and Legacy of New York’s First Asian Gay Bar” is a priceless exhibition of archival photographs and other media on view at Gallery 456 of the Chinese American Arts Council (CAAC), which transports visitors back to a time and place that is all but forgotten in public memory.

From 1993 to 2013, The Web occupied a multilevel space on 58th Street between Madison and Park Avenues, across from Bloomingdale’s. It was established by Shanghai-born CAAC founder and director Alan Chow, and his business partner, Chan.

Chow arrived in New York City in the early 1970s with a background in film acting and directing in Hong Kong. He soon grew aware of the discomfort many immigrant Chinese and Asian gay men like himself felt in mainstream gay bars. The opportunity to open a bar “of our own” presented itself when a fire-damaged lounge off the gay beaten track of downtown Manhattan came available in midtown at below-market rent.

Not only was the price right, so was the timing. At that very moment, diverse communities were stepping out from beneath the generic queer umbrella to express culturally distinctive identities and experiences. There was an upsurge in Asian LGBTQ organizing and visibility (Gay Asian & Pacific Islander Men of New York, GAPIMNY, was founded in 1990).

The Web quickly amassed a loyal clientele. It evolved from a destination to dance and date, to hosting special events like the “Asian Prince” male beauty pageant and gay weddings before same-sex marriage was legalized in 2015. As its reputation grew, the venue attracted celebrity visitors, often by Chow’s invitation or connection. Actress Zhang Ziyi of “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” fame was photographed there.

“The initial Chinese name of the club means ‘web,’ and inside the bar we actually installed a giant net,” Chow said in a published interview. “Guests could climb on it and play around.”

The Web’s biggest public showing was a dazzling float it sent down Fifth Avenue in the yearly Pride Parade, the first time a float of all-Asian drag queens and go-go boys was entered. It won “Best Float” four years in a row.

Photographs of all these activities and events, some taken by Chow himself, some by unknowns, lay unseen in the CAAC files for decades until art photographer Yukai Chen, the current CAAC program manager, stumbled across them and was captivated.

“It’s so avant-garde,” said Chen, a New Yorker of Chinese origin who was barely 13 years old when The Web closed in 2013. “The photos, when you see them, you feel like it’s so modern. People don’t feel like it is back in the nineties.”

The idea for an exhibition was born.

Upon entering the gallery space, you are met with a full-wall photo of chiseled men in teeny-tiny gold lamé skirts, dancing atop the brightly colored Pride float. This leads into a trail of smaller photos and archival media clippings that picture them along the parade route. You are then plunged into the bar itself, witnessing various artsy-erotic goings-on, images of dancers, patrons, and special guests. Installed in the center of the space is a recreation of a table at “Sarong Sarong,” the Malaysian-themed restaurant, also now defunct, that Chow opened on Bleecker in extension of The Web.

As lead artist of the exhibition, Chen produced an accompanying zine that features a lengthy interview with Chow and the celebrated painter Chen Danqing, in whom Chow entrusted the bar’s interior design. Danqing painted striking murals representing “east meets west” on the wall’s of bar’s basement level, visible in the background of several of the photos.

The Web’s main attraction was its bevy of loinclothed go-go boy dancers. They hailed from various East Asian countries — China, Japan, Vietnam, among others — and made anywhere between $250 and $3000 a night in tips, Chow and Chen said.

No shortage of photos in the exhibition capture their presence. Muscled or smooth, projecting seductive stares or disarming smiles, most of their names and lives post-Web are now unknown.

“They are probably in their late fifties, early sixties now, these go-go boys,” Chen said.

One photograph begs a question about the audience’s gaze: a close-up of a go-go boy oiling his bare torso while in the background a white guy ogles him.

In the nineties when these men were working, outward expressions of racial fetishization were far more explicit in gay life, night and day. There was even a lexicon to describe it. White men who sexually fixated on East Asian men were “rice queens”; those who pursued South Asians were “curry queens”; “chocolate queens” were into Black men; and “snow or vanilla queens” were men of color who exclusively pursued white men.

An estimated 30 to 50 percent of The Web’s clientele at its peak were white gay men, skewing above 40.

“I don’t know how people felt back then,” Chen said. “But, Alan told me, ‘Asian people don’t buy drinks that much.’ Maybe the white people contributed a lot to the revenue.”

“I often felt sympathy for some of the older white gay men,” Danqing says in the zine interview. “Shy, lonely, yet, as long as they could spend an evening in an Asian gay bar, they were happy.”

I visited The Web a couple of times myself. I was Black, which I still am, and young, which is now debatable. While the circumstances and motivations for going there are lost in the morass of nightclub visits I made back in the day, I clearly remember the vibe of the place. It was gay first and foremost, yes, but the gay authority there was different from the one calling the shots, literally and figuratively, in most other gay venues.

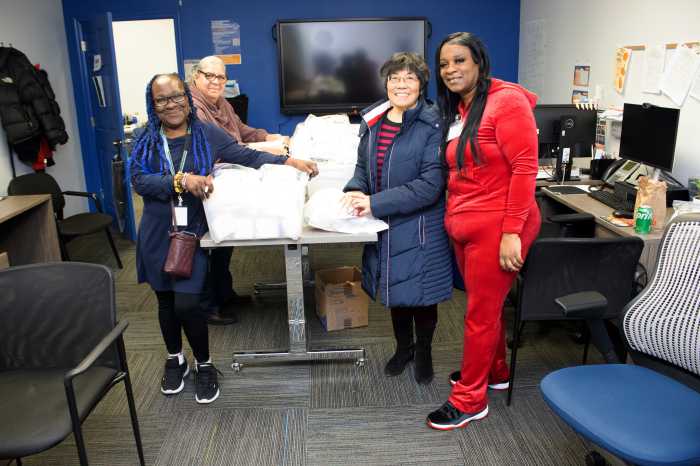

“I remember you,” Chow said to me when I met with him at the exhibition last week, clearly jocularly, but with the warmth of welcome the proprietor of any successful establishment knows how to give.

Then, he took me by the wrist and said, “Let’s take a picture.”

The Web: The Birth and Legacy of New York’s First Asian Gay Bar | Gallery 456 | Until Dec. 5, 2025

Nicholas Boston, Ph.D., is a professor of media sociology at Lehman College of the City University of New York (CUNY). Follow him on X @DrNickBoston and Instagram @Nick_Boston_in_New York