The venerable Oratorio Society has played a central role at Carnegie Hall from the start; their music-making, by a huge chorus including both professional and avocational singers, recalls 19th century practice when choral work played a greater role in civic life. Bach’s “Mass In B Minor” (May 8) had some strong moments due to Kent Tritle’s knowing conducting, but some of the slower movements sounded underrehearsed with cloudy ensemble, which is one of the perils of old-school Bach style as opposed to fully professional, much smaller groups adaptable to swifter tempos.

Among the well-matched soloists, Emily Donato’s fresh, unclouded soprano gave pleasure throughout, both in solos and her duets with the awesomely dark-voiced mezzo, Lucia Bradford, who particularly cleaned up in her “Agnus Dei.” Out tenor Brian Giebler certainly commanded the needed style. Sidney Outlaw, as a baritone, understandably fared best in the upper part of his bass assignment; the voice moves very nicely and sounded particularly focused on “Et in Spiritum Sanctum.” The three trumpeters provided excellent service throughout the evening.

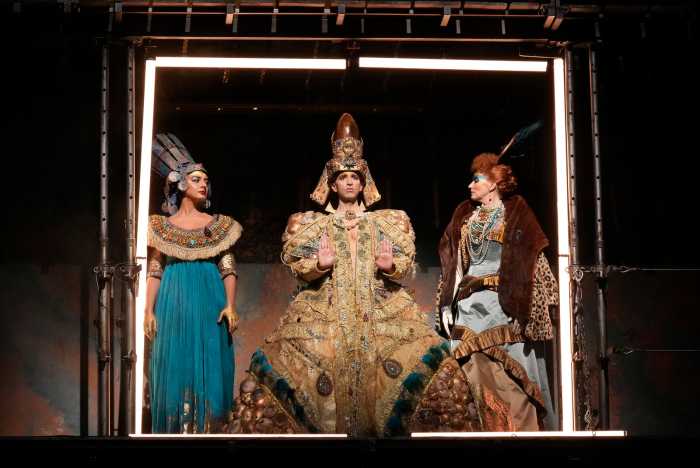

Speaking of trumpeters, the Met’s onstage complement of them in the Triumphal Scene, “Aida,” gave off their usual thrills — as did the unaccompanied men’s chorus in the Prayer Scene when the company gave what was billed as its last performance ever of Sonja Frisell’s gargantuan, traditional 1988 show. As a student I stood through that in its first season. Though far from the stagings I seek out these days, I confess I took pleasure in knowing it was always there to display a certain side of New York to visitors. On May 18 the crowd applauded every set, every horse, and every high note. A great time was had, despite most of the principals being little more than professionally “acceptable.” The standout was the well-paced, intelligently shaded Amneris of Olesya Petrova.

The next night, the Met opened McBurney’s well-traveled production of Mozart’s “Die Zauberfloete.” There was much to enjoy in this spare, yet technically savvy “show ’em the mechanics” exercise. But, unlike with great “Flute” productions, including previous Met shows designed by Chagall and Hockney, this isn’t one I’ll want to experience often.

Musically, things were very enjoyable under Nathalie Stutzmann’s expert baton, save for when Gareth Fry’s aggressive sound design distorted the score and our experience of live music. Way too much atmospheric noise intruded throughout — and almost Broadway levels of wondering from where speech was emanating.

Nor did I really want to hear a volley of violent noise two bars before the end of Erin Morley’s beautifully limned “Ach, ich fühl’s.” As ever, the soprano sounded a little scanty down below, but otherwise enchanting. Lawrence Brownlee’s Tamino — a good sport about performing in underwear — showed both the flexibility and metal of his fine tenor; it is good to see him back at the Met. Clearly the world’s leading Queen of the Night, Kathryn Lewek, sang a superb, touching first aria. But, though still impressive, Lewek wasn’t on her usual blazing form for the show-stopping second one.

Otherwise, the best singing came from the well-matched Three Ladies (Alexandria Shiner, Olivia Vote and Tamara Mumford) and the unusually sonorous Monostatos of Brenton Ryan, styled as a Jared Kushner corporate tool. One could tell that debutant Thomas Oliemans is an intelligent artist, but I didn’t enjoy his scratchy baritone (even if, yes, the original Papageno was an actor, not a singer). Much of Papageno ‘s business seemed tritely familiar. This was a quite good Mozart evening after the house’s wonderful new “Don Giovanni” earlier in the month.

Lucia Bradford was again on the bill at June 9’s highly enjoyable “Harlem Songfest II,” held by the Harlem Chamber Players at Columbia University’s Miller Theatre. Now under Damien Sneed, a musician accomplished in multiple genres, the now 15-year-old HCP provides a range of musical opportunities to serve the Harlem community, with a special mission for serving youthful and elderly audiences. Sneed led off with his fine orchestration of Scott Joplin’s upbeat Overture to “Treemonisha,” hopefully coming soon to a local stage.

The dynamic Bradford set a high bar in a trenchant “Iris, hence away” and moved us in the plaintive “My son, my child” from Mary Watkins’ 2022 “Emmett Till.” Though singing with passion, Janinah Burnett was overmatched by Verdi’s “Pace, pace,” saved by her thrilling high B flat. Her high-lying soprano shone brightly as Strauss’ Sophie and in the Voodoo Queen’s glittering aria by pioneering Black opera composer Harry Lawrence Freeman (1869-1954). Incisive, highly musical character tenor Martin Bakari attained grace in Sneed’s “There is a Balm in Gilead,” scored for strings. Kenneth Overton brought his potent middle register and engaging presence to the still-resonant “Fourth of July speech” from “Frederick Douglass” (1985) by Dorothy Rudd Moore (1940-2022). The revelation was Jasmine Muhammad, whose full, high-quality lyric soprano and intelligence lit up “My Man’s Gone Now” (of which Leontyne Price observed, “Gershwin knew where the bodies were buried”; so do Muhammad and Sneed) and Micäela’s aria from “Carmen.” Bizet’s evergreen tunes — well served — rarely miss. Bradford conquered with a sly, dynamically sensitive “Habañera.” Overton showed the dramatic chops, if not the steady high Fs, for the cruelly written Toreador Song, but to see the three divas reacting to his overtures was worth the price of admission. Everyone sounded terrific in the dreamy “Rosenkavelier” trio and Margaret Bonds’ “He’s Got the Whole World” setting.