In the last couple of years, there’s been an invigorating new wave of books documenting lost and current queer spaces in New York City. Among them are “Drag Explosion,” featuring Linda Simpson’s rare photos of the underground club scene in the 1980s and ’90s; “Glitter and Concrete,” a cultural history of drag; and “Bartschland,” tracing decades of Suzanne Bartsch’s fabulously queer parties.

For my part, I am gratified to be part of this renaissance in chronicling LGBTQ history. Recently, I published a history of gay clubs in Manhattan titled “GETTING IN,” showcasing my collection of flyers from the 1990s. Nightlife guru Michael Musto wrote the foreword.

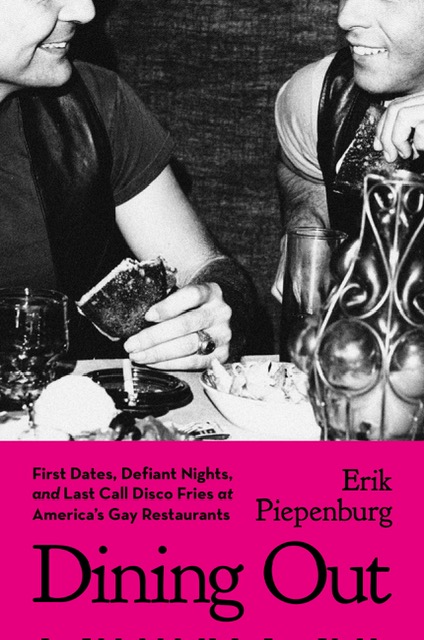

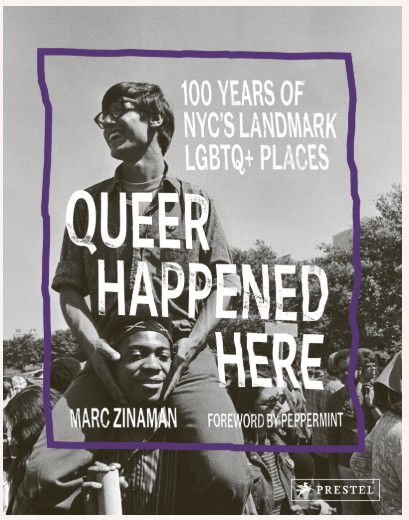

And now, there are two more books focusing on queer spaces, “Dining Out: First Dates, Defiant Nights, and Last Call Disco Fries at America’s Gay Restaurants,” by Erik Piepenburg, and “Queer Happened Here: 100 Years of NYC’s Landmark LGBTQ+ Places,” by Marc Zinaman. I had the chance to speak to each of these first-time authors about the inspiration behind their works.

Journalist Piepenburg hit on the idea of creating “Dining Out” while writing a piece on gay restaurants for The New York Times in 2021.

“I came out in the 1990s when gay restaurants were everywhere,” he said, citing the gayborhoods of Chelsea in New York, Boystown in Chicago, and Dupont Circle in Washington, DC, where he lived during that period. “I thought that the idea of the gay restaurant was dead, but I was wrong.”

During the course of his research, he discovered that such eateries are largely thriving, especially in pockets like San Diego and Palm Springs, though not as briskly as in the ’90s. He estimated that roughly 30% of the restaurants mentioned in the book are still open.

“I had so much material, and there is no book that I’ve found that’s just about gay restaurants,” he explained. “So I thought, ‘Well, I’m going to turn this article into a book.’ And so here we are four years later.”

According to Piepenburg, much has been written about the cultural significance of gay bars, but not eateries. “No one had ever asked me, ‘Oh, what was your favorite gay restaurant?’” He vowed to change that.

Another revelation? These restaurants are serving a purpose well beyond food.

Piepenburg asserts that gay dining spots have for decades played crucial roles in gay activism, social life, sexual life, and romantic life. They have served some of the same purposes as bars have.

“One of the things that did surprise me was that gay restaurants in the 1960s and ’70s certainly were these places of escape where you could be your true self and also sit down to an actual dinner,” he said. A recurring theme throughout the book is the role of restaurant as social hub and even refuge. Historically, LGBTQ folks have been maligned and marginalized, and they have needed a safe space — beyond the bars and clubs — to be themselves.

A chapter about the “Golden Age” of gay restaurants fondly recalls shuttered New York haunts like Food Bar and Big Cup on Eighth Avenue in Chelsea, near the way-gay gift shop Rainbows and Triangles. Also noted is the now-demolished Howard Johnson’s in Times Square, frequented by male strippers from the Gaiety burlesque theater next door.

You’ll find an entire chapter about the “game-changing” Florent, located in the then-desolate Meatpacking district in the 1980s and ’90s, and one about Lucky Cheng’s, the Asian fusion restaurant that boasted alluring servers of Asian heritage, who dressed in drag or who were transgender. (Fun fact: the site was once Club Baths, a notorious gay bathhouse, and many of the original fixtures were repurposed.)

So, what exactly is a gay restaurant?

“If you ask 10 different gays, they’ll come up with 10 different answers,” he said. “But in my book, I define a gay restaurant as where, when you walk in the door and look around, mostly gay people are eating there.”

He recalled going to Florent at 3 a.m., where he found a heady mix of club kids, designers, artists, Chelsea boys, and drag queens partying. The proprietor, Florent Morellet, boldly announced he was HIV-positive by posting his T-cell counts on the wall menu along with the daily specials.

Piepenburg included other personal favorites, like the “legacy restaurant” Annie’s in Washington, DC, and his beloved Melrose Diner in Chicago. He traversed across America to research legendary spots he’d only heard about, such as Gallus, a multilevel restaurant-nightclub on the outskirts of Atlanta; Orphan Andy’s, a comfort-food diner in San Francisco’s Castro district; and Nepalese Bar and Grill, a haven for trans and non-binary folks in Green Bay, Wisconsin.

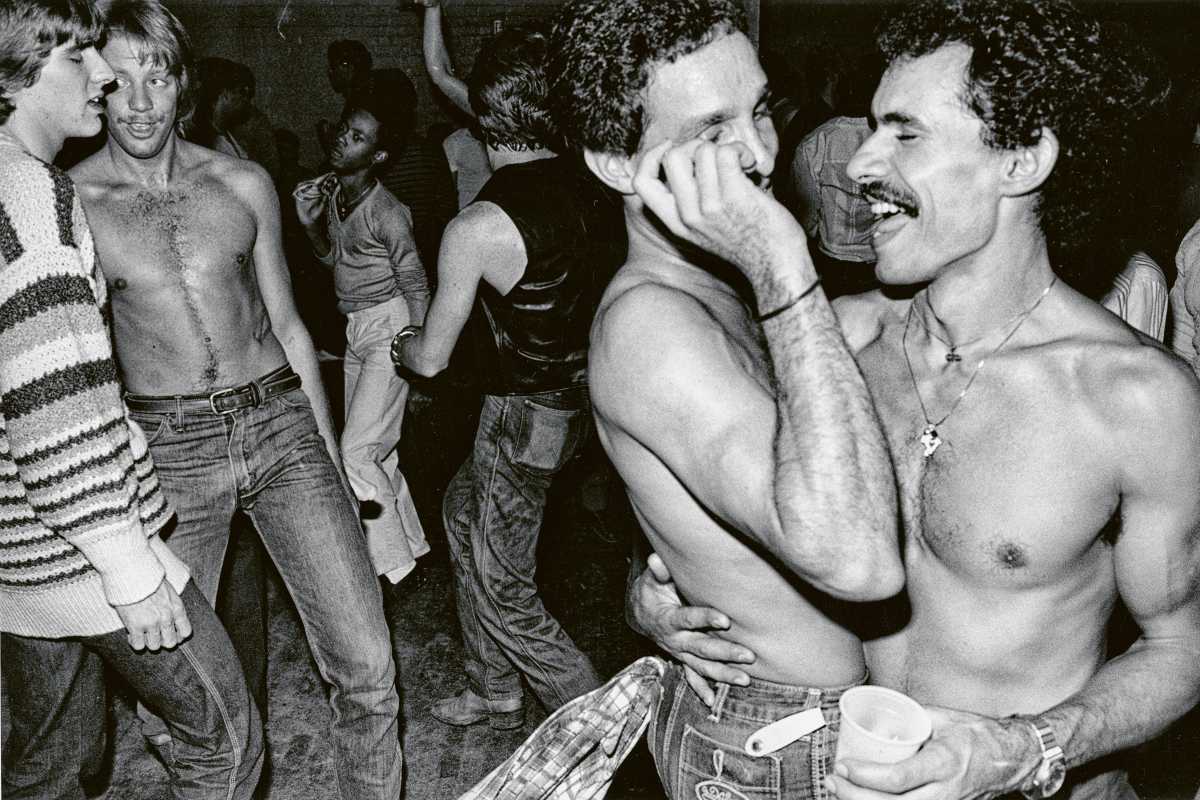

One revelation was the profusion of eateries within gritty, decidedly unsavory spaces like bathhouses or leather bars. For example, not only did the old Eagle bar in New York City dish out burgers and buffet brunches for decades, but starting in the 1970s they served upscale fare like roast Long Island duckling in orange sauce and baked Alaska.

“It was a one-stop shop for food and kink,” Piepenburg said with a chuckle. The book has an entire chapter about such eateries, wryly titled “Bread and Butt.”

Not that “Dining Out” is simply a straightforward inventory of these spaces. Piepenburg ended up inserting himself in the story, which, as an objective journalist, he is somewhat loath to do.

“My editor was like, ‘We want you to take us on this journey,’ but that creeped me out a little bit,” he said. He included personal anecdotes of first dates, delicious or not-so-delicious dinners, or poignant interviews with former restaurant workers recalling their glory days.

Personally, I found these stories not only engaging but affecting as well. Like the one about Flex, a mega bathhouse in Cleveland, located in a former Greyhound bus terminal, where the owner, Rick, insists on serving meals on holidays. Rick recalled when a gentleman thanked him profusely, to which he responded, “There’s no reason why you have to spend the holidays alone.”

During our in-person chat, this triggered an emotional response from Piepenburg.

“There are certain parts of this book where I just start crying,” he admitted, noting that Flex is a refuge for older single gay men, perhaps whose partners have died or were spurned by their families, looking to enjoy a meal together every Sunday and on Thanksgiving and Christmas.

When asked which restaurant he’d like to visit in a time machine, without hesitation Piepenburg answered Gallus in the early 1980s. He described it as a “gay restaurant department store,” where on the main floor was a restaurant that served up an elevated dining experience amid chandeliers, white tablecloths, fresh flowers, and steaks. Upstairs was a piano bar/cabaret where you could enjoy an after-dinner drink and dessert, and in the basement was a lounge where you could cavort with the hustlers. Gallus closed in 1993.

“I think it’s important to preserve this queer history because gay restaurants are distinct from gay bars and serve different purposes and different communities,” he said. “It’s a queer space that is undervalued. And I want to honor those gay elders who came before me.”

It should come as no surprise that preserving LGBTQ history is also the primary aim of Marc Zinaman’s “Queer Happened Here,” an expansive, copiously illustrated account of scores of queer spaces in New York City over the last century. (Full disclosure: We assisted with each other’s books.)

As with Piepenburg’s “Dining Out,” the genesis for Zinaman’s book was also sparked in 2021 by serendipity. That was the year he launched Queer Happened Here, an Instagram page that gained surprising traction from day one. Although it proved an ideal format for user engagement with quick, bite-sized four-paragraph posts sporting eye-popping photos, he wanted an alternative way to connect with those not on social media.

“[The book] is a more long-term format conducive to preserving this history,” he said. “In theory, Instagram can delete my whole account any day it wants.”

Choosing which venues to highlight was a tricky, multilayered process. According to Zinaman, he needed to limit the scope to Manhattan because of space constraints. He started with places that were intriguing to him personally, like the Pyramid Club, The Saint, and Paradise Garage. Then he made sure to include iconic, legendary spaces like Stonewall and Studio 54.

Another consideration was that, as a coffee table book, it required compelling imagery. Many places, especially those from the earlier decades, simply didn’t have imagery available. What’s more, it was not always possible to obtain the publishing rights. “And so that sort of ended up dictating what did and did not get included,” he said.

Not that Zinaman only focused on nightlife spaces. He made sure to include a range of venues — even outdoor cruisy spots like the Ramble in Central Park and the Hudson River Piers in the West Village.

“We’ve found each other in all kinds of spaces,” he said. “And the piers are interesting because we took them over because they were dilapidated and no one else was going to them. And that led to them being refurbished and made all shiny and new.”

“I’m constantly redefining what is a queer space,” he continued, noting that he has expanded into categories like restaurants, gyms, community centers, and other facilities vital to the LGBTQ community.

“Queer Happened Here” is not only bent on inclusivity of a variety of spaces, but also diversity across the LGBTQ spectrum in terms of race, gender, or sexual identity.

“I wanted to include places that I felt captured a very diverse set of the queer community, not just the cis gay male community,” he explained. “I tried to throw in a little bit of everything.”

Zinaman made sure that spaces key to particular niches of the community were included, such as Lucky Cheng’s, which first opened in the East Village in 1993.

“It was really important to the queer Asian community at the time,” he said. “And for queer, trans and effeminate Asian men who not always felt welcome at other gay spaces.” He even included the short-lived Club Casanova, which helped jumpstart the Drag King movement.

When asked if there were any venues he particularly regretted having to cut, he answered Splash, the innovative, wildly popular bar in Chelsea in the 1990s and 2000s. He researched and wrote about Splash and even sourced photos.

“I wrote each entry for each club separately, and then when I put them all together, I had twice as long of a book as I was allowed to have,” he recalled. “And so that merited a lot of cutting, both by me and by [my publisher].”

According to Zinaman, Splash was important not only to New York City gay history, but also to his own history, since it was one of the first gay bars he ever visited. To compensate, he managed to sneak a mention of Splash in the book’s intro.

One of the most interesting facts he uncovered during his research was the extent the Mafia controlled the operation of LGBTQ bars. This shady practice went on for decades in the mid 20th century.

“The more I dove into it, the more I realized that, yes, the mafia did it to make money off of a targeted, vulnerable community. But at the end of the day, they also protected the LGBTQ community and often forged relationships with them.”

He told the story of Anna Genovese, the wife of the infamous mafia boss, who ran a pair of female and male impersonation nightspots called Club 181 and Club 82 in the East Village, from the 1940s through the ’70s. She ended up having love affairs with some of the lesbian performers at the club.

Like Piepenburg’s “Dining Out” — and, for that matter, many of the new wave of books about noteworthy queer spaces — “Queer Happened Here” leans heavily into the importance of these queer spaces as community builders and safe havens. Zinaman believes that they were the only spaces where people could feel comfortable going to and not risking harassment, physical harm, or arrest.

He also mentioned that bathhouses often offered gyms, cafés, and musical performances. And when the AIDS crisis hit in the early 1980s, they became conduits for safe-sex education and activism.

Zinaman posits that places like St. Marks Baths and the Everard Baths were much safer than hooking up at night in spaces like the piers. Plus, they were about much more than sex.

“You end up building community because you’re having your meals there, you’re sleeping there, you’re waking up there, you’re having your coffee there. You’re just hanging out and making friends, some of whom are lifelong.”

Aside from a smattering of historical plaques, noteworthy queer spaces from the past have largely remained forgotten or invisible. “Dining Out,” “Queer Happened Here,” and other books in the new wave of queer histories document and celebrate the extraordinary resilience of LGBTQ culture, in New York City and beyond.