(Note: spoilers for “Midnight Cowboy.”)

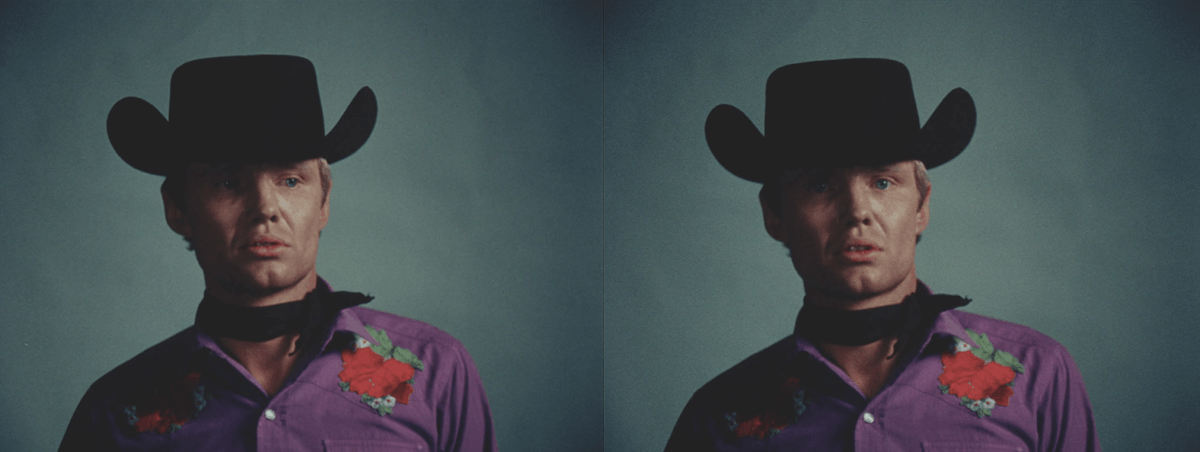

54 years after it was made, “Midnight Cowboy,” which won the Oscar for Best Picture in 1970, looks like a path not taken — or, more accurately, quickly abandoned — by Hollywood. Directed by gay British filmmaker John Schlesinger, it offers an outsider’s view of life in New York. Joe Buck (Jon Voight) arrives here from a small Texas town and ends up in sex work, servicing both men and women. He carries his own issues, including a repressive religious background and surviving a sexual assault.

He meets up with the sickly petty crook Ratso Rizzo (Dustin Hoffman), and although the dialogue is full of casual slurs, they’re obviously in love. The emotional support they offer each other has to be justified to themselves by saying “faggot” regularly (and, for Buck, beating up one of his clients.) The film’s style draws on the French New Wave and ‘60s American underground films, with very quick editing, interpolation of TV clips, and switches between black and white and color. In some respects, it’s dated, especially if you’re familiar with its influences (the psychedelic party scene, which pays direct tribute to Andy Warhol’s films, looks rather silly), but the emotional underpinnings are quite moving. It’s rough enough to dodge sentimentality, but not so much that it runs away from an undercurrent of optimism.

In only 100 minutes, Nancy Buirski’s documentary “Desperate Souls, Dark City and the Legend of Midnight Cowboy” covers far more ground than the simple behind-the-scenes look it could have been. In fact, it endeavors so hard to place “Midnight Cowboy” in the context of its times that the film itself risks getting lost. Buirski depicts it as the confluence of a number of forces: Schlesinger’s own sexuality, his background in documentary, a growing critical attitude towards the myth of the cowboy spurred on by the Vietnam War, a rising fascination with New York as “the seventh circle of hell” (as film critic J. Hoberman describes “Taxi Driver”). It threatens to offer so much context that “Midnight Cowboy” itself gets swamped. From the images of the Vietnam War in “Desperate Souls,” one would be surprised that “Midnight Cowboy” barely alludes to it.

However, the access Buirski received and the quality of her interviews (with actors Jon Voight, Jennifer Salt and Bob Balaban, as well as trans writer Lucy Sante and others) keep her film grounded. All speak intelligently. (Compared to Voight’s right-wing rants on social media, he’s on his best behavior here.) While Schlesinger died in 2003, Buirski makes use of an audio interview with him. The structure at first seems a bit haphazard, but it manages to bring together short sections on everything it wants to say. While the danger of romanticizing the ‘60s (as well as a reliance on overly familiar clips of icons like Jimi Hendrix and Malcolm X) always looms, “Desperate Souls” keeps reminding us that the lifting of repression fueled the energy of “Midnight Cowboy” and shows how quickly images of New York turned even bleaker. Hoberman is right to say that next to Travis Bickle, Rizzo is a sentimentalized character. Still, the edge of optimism in “Midnight Cowboy,” even though it ends with the death of one of its heroes, keeps it from staggering off into the trendy pessimism of “Easy Rider,” made the same year.

Abbie Hoffman, who became friends with Voight, wanted the actor to boycott the 1970 Oscars to protest his trial. While Voight went anyway, he lost the Best Actor nomination to John Wayne in “True Grit.” One of the most fascinating sections of “Desperate Souls” runs through the history of the Western. The “midnight cowboys” of 42nd St. were a real phenomenon: hustlers dressed in macho drag, drawing on the movie iconography of the cowboy. The cowboy’s machismo was supposed to epitomize heterosexuality, but Warhol’s “Lonesome Cowboys,” made a year before “Midnight Cowboy,” had already turned it gay.

In a better world, Hollywood would have embraced queer liberation in the ‘70s and moved from bromances charged with internalized homophobia into a romance between men. Instead, the freedoms of New Hollywood rarely extended to queerness. Schlesinger had to go back to England to make “Sunday, Bloody Sunday,” a love triangle between a gay doctor, a heterosexual woman, and the bi man who sleeps with both.

Looking back at “Midnight Cowboy,” its treatment of class seems more radical than its depiction of sexuality (Balaban says that his character’s scenes, in which he goes down on Joe Buck in a movie theater and then gets robbed by him in the bathroom, were cut for TV broadcast.) While Hollywood is still reluctant to make films with gay heroes, the idea of mainstream media with queer people at its center is no longer radical. (“Desperate Souls” brings up ‘60s British films like Basil Dearden’s “Victim” and bi director Tony Richardson’s “A Taste of Honey” as precursors.) Poverty has become far more invisible in American movies than it was in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. Part of the strength of “Midnight Cowboy” is that its politics are inchoate rather than preachy, but when are we going to get a new Best Picture winner about a man who dies because he can’t afford health care?

“Desperate Souls, Dark City and the Legend of Midnight Cowboy” | Zeitgeist/Kino Lorber | Directed by Nancy Buirski | Opens at Film Forum June 23rd