Jameka K. Evans. | LAMBDA LEGAL

In what could prove a pivotal step in the long road toward full equality under the law, Lambda Legal has announced it will petition the Supreme Court to decide whether Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which bans employment discrimination because of sex, also bans discrimination that is based on sexual orientation.

Lambda signaled its intentions on July 6, after the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals, based in Atlanta, announced that its full bench would not reconsider a three-judge panel decision from March 10 rejecting a sexual orientation discrimination claim by Jameka K. Evans, a lesbian security guard, against her former employer, Georgia Regional Hospital.

The argument that Title VII should be interpreted to cover sexual orientation claims got a big boost several months ago when the full bench of the Chicago-based Seventh Circuit ruled that a lesbian academic, Kimberly Hively, could sue an Indiana community college for sexual orientation discrimination under the federal sex discrimination law, overruling prior panel decisions from that circuit.

With appeals courts in Chicago, Atlanta split on protections under ‘64 Civil Rights Act, issue ripe for review

The Seventh Circuit was the first federal appeals court to rule that the 1964 Act provided such protections. Lambda Legal represented Hively in that appeal.

Interestingly, Title VII did not even include sex as a prohibited ground of discrimination when the Civil Rights Act got to the floor of the House of Representatives for debate. The measure’s primary focus was race discrimination. But a Virginia representative, Howard W. Smith, an opponent of the bill, introduced a floor amendment to add sex, in an apparent effort to add a poison pill making the measure too controversial to pass. Smith’s amendment won the support of similarly-minded conservatives but also from liberals interested in advancing the employment rights of women. Smith’s effort backfired when the amended bill passed the House and was sent to the Senate.

There, a lengthy filibuster over the race discrimination provision delayed a floor vote for months, but when it was eventually passed, there was not much discussion about the meaning of sex as a prohibited ground for employment discrimination. (The sex provision did not apply to other parts of the 1964 Act, so employment protections are the only portion of that statute that outlawed sex discrimination.)

Within a few years, both the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and federal courts had issued decisions rejecting discrimination claims from LGBTQ plaintiffs, holding that Congress did not intend to address homosexuality or transsexualism (as it was then called) in the 1964 law. That judicial consensus did not start to break down until after the Supreme Court’s 1989 “sex-stereotyping” decision in Ann Hopkins’ sex discrimination case against Price Waterhouse. There, the high court concluded Hopkins was illegally denied partnership because senior members of the firm believed she did not conform to their image of a proper “lady partner.”

Within a few years, litigators began to persuade federal judges that discrimination claims by transgender plaintiffs also involved sex stereotyping. By definition, a transgender person does not conform to stereotypes about their sex as designated at birth, and by now a near consensus has emerged among the federal courts of appeals that discrimination because of gender identity or expression is a form of sex discrimination under the stereotyping theory. The EEOC changed its position as well, following the lead of some court decisions, in 2012.

Advocates for gay plaintiffs also raised the stereotyping theory, but with mixed success. Most federal circuit courts were unwilling to accept it unless the plaintiff could show that he or she was gender-nonconforming in some obvious way, such as effeminacy in men or masculinity (akin to the drill sergeant demeanor of Ann Hopkins) in women. The courts generally rejected the argument that discrimination based on an employee’s homosexual or bisexual orientation, in and of itself, was proof that their employer impermissibly acted based on stereotypes of how a man or woman was supposed to act. Some appellate courts, including the New York-based Second Circuit, ruled that if sexual orientation was the “real reason” for discrimination, a Title VII claim must fail, even if the plaintiff was gender-nonconforming.

Within the past few years, however, several district courts and the EEOC accepted the stereotyping argument and other arguments insisting that discrimination because of sexual orientation is always, as a practical matter, about the sex of the plaintiff. But it was only this year that a federal appeals court — the Seventh Circuit in the Hively case — came around to this view.

A split among the circuits about the interpretation of a federal statute is a key predictor of a case the Supreme Court is likely to accept for review. Until now, the high court has always rejected the invitation to consider whether Title VII could be interpreted to cover sexual orientation and gender identity claims, leaving in place lower court rulings that found otherwise.

In 2016, however, the high court signaled its interest in the question whether sex discrimination, as such, includes gender identity discrimination when it agreed to review a ruling by the Richmond-based Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, which held that the district court should not have dismissed a sex discrimination claim by Gavin Grimm, a transgender high school student. Grimm, who was denied access to the boys’ bathroom appropriate to his gender identity by his Gloucester County, Virginia, school, filed suit under Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, which bans sex discrimination by schools receiving federal money.

The Fourth Circuit found that the district court should have deferred to the Obama administration’s Department of Education interpretation of the Title IX regulations, which tracked the EEOC and federal courts in Title VII cases and accepted the sex stereotyping theory for gender identity discrimination claims. Shortly before the Supreme Court was scheduled to hear arguments in the Grimm case, however, the Trump administration withdrew the Obama DOE interpretation, pulling the rug out from under the Fourth Circuit’s decision. The Supreme Court canceled the argument and sent the case back to the Fourth Circuit, which this fall will hear argument on the question whether Title IX would protect a claimant like Grimm even without an interpretation from the Executive Branch.

Meanwhile, the Title VII issue has been percolating in many courts around the country. Here in New York, several recent Second Circuit appellate rulings, citing existing circuit precedent, have denied sexual orientation discrimination claims. In some of those cases, judges said that the gay plaintiff could maintain their Title VII case if they could show gender-nonconforming behavior sufficient to evoke the stereotyping theory. And in one case, the circuit’s chief judge wrote a concurring opinion suggesting it was time for the full bench to reconsider the issue. In another case, Zarda v. Altitude Express, the court recently granted a petition for such reconsideration, with oral argument scheduled for September 26. The EEOC, many LGBTQ rights and civil liberties organizations, and the attorneys general of the three states in the circuit — New York, Connecticut, and Vermont — have filed amicus briefs, calling on the Second Circuit to follow the Seventh Circuit’s lead on this issue.

The timing in the 11th and Second Circuit cases makes for an interesting dynamic. Lambda’s petition for Supreme Court review of the 11th Circuit case must be filed within 90 days of the denial of its rehearing petition — that is, by early October. Georgia Regional Hospital would then have 30 days to respond, so a Supreme Court decision on whether to take the case could well not come until late October, early November, or later. If the court accepts the case, oral argument would follow in early 2018, with a decision by next June.

The question then is how expeditiously the Second Circuit would move in the Zarda case. Legal observers generally believe the circuit is poised to follow the Seventh Circuit’s lead in holding that sexual orientation claims can be litigated under Title VII, but the circuit’s judges may see it as prudent to hold up until the Supreme Court either rejects review of the 11th Circuit case or rules on it.

However, two veteran Second Circuit judges have recently bucked the circuit precedent, arguing it is outmoded and refusing to dismiss sexual orientation cases. A few years ago, the circuit accepted the argument in a race discrimination case that an employer violated Title VII by discriminating against a person for engaging in a mixed-race relationship. Some judges see this as support for the analogous argument that discriminating against somebody because they are attracted to a person of the same-sex is sex discrimination.

It’s worth noting that in the past the Second Circuit moved to rule quickly on an LGBTQ issue in a somewhat similar situation. When lawsuits challenging the Defense of Marriage Act were moving through the federal courts in 2012, there was a race among cases from the Second Circuit, Boston’s First Circuit, and San Francisco’s Ninth Circuit. The Supreme Court had already received a petition to review a First Circuit case — where GLAD, the GLBTQ Legal Advocates & Defenders, represented the plaintiffs — before the Second Circuit heard the American Civil Liberties Union’s suit on Edie Windsor’s behalf. But the Second Circuit moved quickly, and in the end it was the ACLU-Windsor case the high court accepted. On June 26, 2013, ruling in the Windsor case, the Supreme Court gutted the key provision of DOMA.

If the Second Circuit moves quickly again, it could turn out an opinion before the Supreme Court has announced whether it will review the 11th Circuit Evans case. The timing might be just right for that.

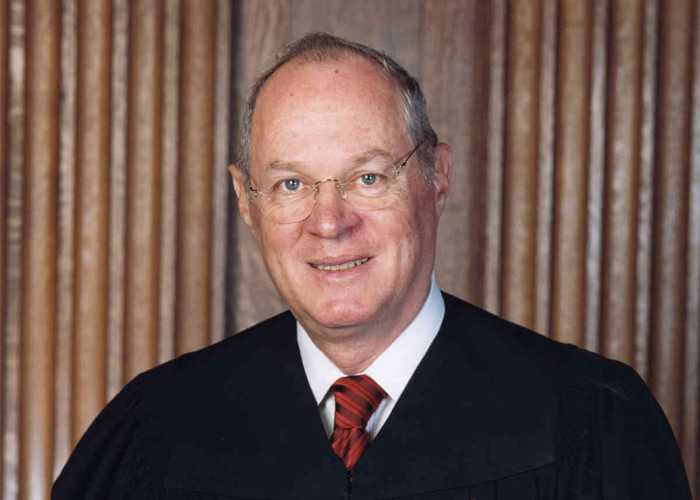

A key concern for LGBTQ legal advocates, of course, is the Supreme Court’s composition at the time this issue is decided. Right now, the five-justice majority in the DOMA case and the marriage equality case two years later holds. But three of them — Justices Anthony Kennedy (who turns 81 this month), Ruth Bader Ginsburg (84), and Stephen Breyer (79 next month) — represent the court’s oldest members, and there have been persistent rumors about Kennedy, who has written all the major gay rights decision over two decades, considering retirement.

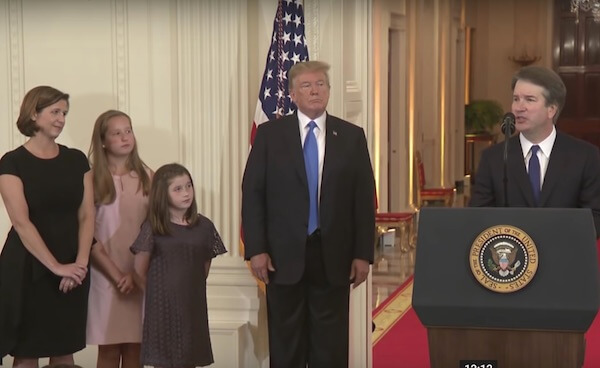

Donald Trump’s first appointee to the Court, Neil Gorsuch, replacing the late arch-homophobe Antonin Scalia, immediately showed his own anti-LGBTQ colors with a disingenuous dissent from a June 26 high court ruling that the 2015 marriage equality decision compels Arkansas to list both mothers on their child’s birth certificate. Another appointment like Gorsuch from Trump would seriously jeopardize the chances for any further progress on LGBTQ rights and equality in the foreseeable future.