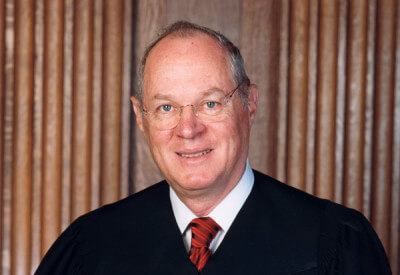

Retired Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy had a propensity to side with conservatives during his time on the bench, but he found exceptions when it came to gay rights — and on that even he himself was caught off guard at times.

Kennedy, who left the high court in July following a three-decade stint, notably authored the 2015 majority ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges, which granted marriage rights to same-sex couples nationwide.

During an episode last week of Bloomberg TV’s “The David Rubenstein Show: Peer-to-Peer Conversations,” the 82-year-old former justice said that in his Obergefell decision he “surprised” himself, noting “his religious beliefs” but also his view that “the nature of the injustice is you can’t see it in your own time.”

While a variety of factors undoubtedly played a role in Kennedy’s thinking, the children of same-sex parents were among those who helped sway his decision on marriage equality.

“As I thought about this, and I thought about it more and more, it seemed wrong — unconstitutional — to say that over 100,000 adopted children could not have their parents married,” he recalled.

Kennedy said that as a judge he strived to take everything into consideration and went to great lengths to avoid allowing pre-existing biases or assumptions to influence his decisions.

“Your duty in every case is to ask why you are doing what you are about to do,” he said. “If you make up your mind in advance, you are not following that oath.”

Appointed by President Ronald Reagan, Kennedy wrote for the majority in the four most consequential Supreme Court rulings to date on LGBTQ rights. Those cases date back to 1996, when the high court ruled against a Colorado voter initiative that denied gay people the right to press for nondiscrimination protections in law.

Seven years later, he wrote the majority opinion in Lawrence v. Texas, invalidating criminal laws against gay sodomy in the US, which overturned the 1986 ruling in Bowers v. Hardwick, a case that had narrowly reaffirmed a sodomy law in Georgia.

In 2013, Kennedy ruled in favor of Edie Windsor in United States v. Windsor, writing that the Defense of Marriage Act “is in violation of the Fifth Amendment,” in denying Windsor her equal protection rights when the federal government refused to recognize her marriage to the late Thea Spyer and imposed an inheritance tax on her.

It is not yet clear how Kennedy’s highly controversial successor, Brett Kavanaugh, will rule on LGBTQ rights issues. Kavanaugh did not answer California Democratic Senator Kamala Harris when she asked him in September to elaborate on his personal opinion of the Obergefell case. Instead, he pointed to the court’s June ruling in Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission — where a baker refusing to make a cake for a gay wedding won a narrowly decided victory — and noted that Kennedy wrote in the majority opinion that the days of discriminating against gay and lesbian Americans are over.

Some have pointed to Kavanuagh’s comments on decisions in other case, however, to predict how he might rule. As the Los Angeles Times noted, he praised former Chief Justice William Rehnquist’s dissent in Roe v. Wade and credited his tenure on the court as “successful in stemming the general tide of freewheeling judicial creation of unenumerated rights that were not rooted in the nation’s history and tradition.”

Whether Kavanuagh considers LGBTQ rights vindicated by the Supreme Court to be products of “freewheeling judicial creation” remains to be seen.