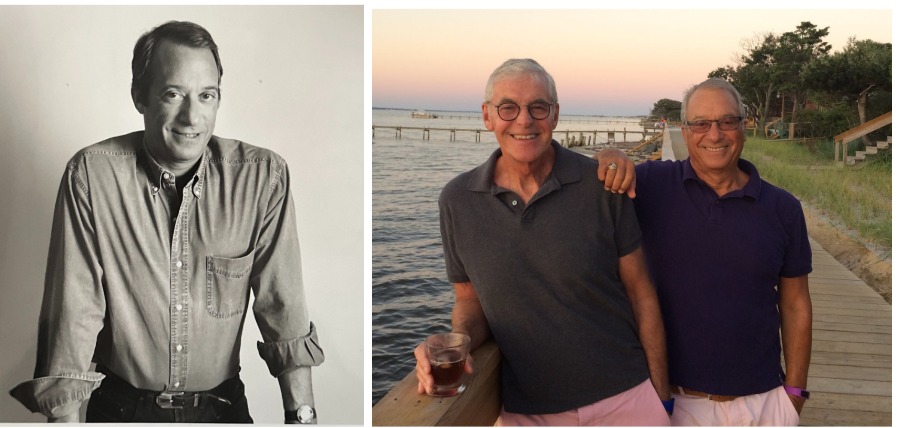

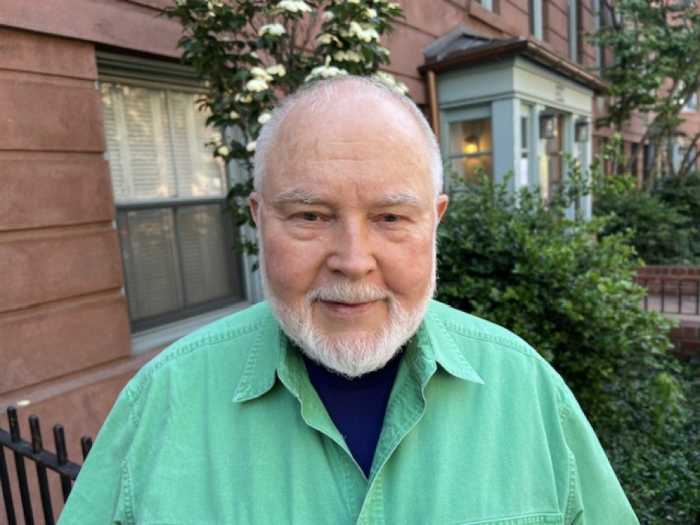

Joe Lovett, who broke ground covering gay and AIDS stories on network television in the ’70s and ’80s and went on to make timely documentaries on everything from cancer to visual impairment to global warming, died July 14 at age 80.

He is survived by his husband Dr. Jim Cottrell, his partner of almost half a century — an epic story in itself.

David Sloan, a senior executive producer of ABC News Studios who became a producer at “20/20” in 1989 when Lovett left after 10 years, said, “Joe Lovett was truly a gift to the queer community because of the fearless reporting he did at ’20/20’ in the early days of the AIDS epidemic, a time when mainstream news media turned a blind eye to that catastrophe. His work was groundbreaking and game changing. Joe was a singular voice in journalism when we needed it the most.”

“Joe used to say that I inherited ‘the gay chair’ at ’20/20′ because we were basically the only two people in all of ABC News who were out of the closet. Hard to imagine!” Sloan said. “He was a role model for me and so many working in TV news, which was a fairly inhospitable place for us.”

Indeed, among his many achievements, Lovett may be most remembered for producing the first network TV news magazine story on AIDS in 1983 on ABC’s “20/20” two years after the syndrome was first identified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Correspondent Geraldo Rivera lacerated the inaction of the Reagan administration and the New York Times and interviewed activist Larry Kramer and Dr. Anthony Fauci, head of the National Institutes of Health.

It also featured people living with AIDS at a time when the cause of the syndrome, HIV, had yet to be identified. While some of the gay men had yet to manifest many outward symptoms, Kenny Ramsaur was shown facially and bodily disfigured by Kaposi’s Sarcoma, an opportunistic infection — contrasted with pictures from when he was a handsome young man. (Watching it in a room full of gay men, we audibly gasped at the contrast and it is indisputable that this segment spurred us on to more urgent action — and even got the Times to change course and finally make AIDS a front-page story.) The 16-minute segment is online at vimeo.com/269698918.

But that’s not the first ground Lovett broke on network television. Around 1974, he started working as an editor and producer at CBS News. His colleague, Martha Spanninger, said, “He was definitely openly gay the whole time I was working with him at CBS News starting in 1977,” unusual in mainstream media and workplaces in general in those days.

He produced “Parents of Gays” on the self-help/activist group that had been founded in 1973 to help parents accept their gay children.

“It aired on CBS News ‘Magazine,’ which was a daytime news magazine geared to women,” Spanninger said. “I remember him talking about an advertiser, Breck, asking to be moved as far away from the segment as possible. It turned out the father in the piece worked for Breck, so the company regretted the move when they saw the segment.”

Writer and gay and HIV activist Sean Strub, founder of POZ magazine, described Lovett as “a classic journalist in all the best ways: a courageous, gutsy truth-teller.”

After leaving “20/20” in 1989, Lovett founded Lovett Productions, Inc. (later, Lovett Stories + Strategies), where he produced, in partnership with the CDC and ABC, “In a New Light” — AIDS awareness primetime specials televised in the 1990s that ran for five years.

“In a New Light: Sex Unplugged” (1995) was about teens and sex was hosted by Rosie Perez and Stephen Baldwin. It featured Melissa Etheridge, Jared Leto, Jon Stewart, Parker Posey, and Greg Louganis, as well as Barbara Walters and former US Surgeon General C. Everett Koop. When the cause was urgent, Lovett could turn out the stars.

“What we’re hoping is that kids will understand the concept of pressure, and if they’re going to have sex, see no problem in using a condom,” Lovett told the LA Times. “We’re hoping that people will talk to each other and to others, their parents included.”

In 2001, Lovett won a Peabody Award and an Emmy nomination for writing, producing, and directing HBO’s “Cancer: Evolution to Revolution,” which was billed as “150 minutes of television that could save your life” and it did start a national conversation about how to cope with, treat, and learn to live with cancer.

Lovett’s first feature film was the eye-opening “Gay Sex in the 70s,” a poignant exploration of the brief period of sexual freedom experienced by gay men between centuries of repression and the tragedy of HIV/AIDS — the joy of sexual freedom shut down shockingly and all too soon by the pandemic. Newsday called it a “bittersweet but blissful recollections of men who can only be described as survivors.” It premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival in 2005 and was broadcast on the Sundance Channel in 2007 and is on YouTube.

As his own eyesight got worse, Lovett made “Going Blind” and conducted an outreach campaign, “Going Blind and Going Forward,” that “ignited a global movement of individuals, grassroots organizations and medical professionals sponsoring screenings to raise awareness and to improve access to vision enhancement services.”

Spanninger said of Lovett’s medical documentaries, “Joe had a colonoscopy on camera because so many in his family died of cancer. When he was ‘going blind’ he did a documentary about that. His life was a journey of listening, learning, educating, enlightening, and soaking up as many pleasures as possible. I worked with Joe and became part of his and Jim’s extended family and fan club. He was always brutally forthright and honest — like his films.”

He also directed or produced such films as “The Way Home,” a one-hour special on forgiveness for the Hallmark Channel, “State of Denial” about the AIDS crisis in South Africa, and again for HBO, “Too Hot Not to Handle” on the global warming crisis.

In addition to his Peabody, Lovett was honored with the AIDS Leadership Award, the Christopher Award, and the Kitty Carlisle Hart Award.

Lovett’s husband, Dr. Jim Cottrell, told Gay City News, “Joe and I met September 27, 1976 at the Jefferson Market over the watercress stand. This was the beginning of our almost 49-year romance.”

Cottrell added: “Joe was working at CBS and I was an assistant professor of anesthesiology at NYU. I was impressed by Joe’s work: He was producing a groundbreaking gay-positive piece about a young man coming out in middle America.

“The medical field was mostly homophobic,” Cottrell said. “I learned from Joe that coming out would not be the end of my career. We began to develop friendships as a gay couple and had the acceptance of most of our family members. It wasn’t long till our friends started dying of weird diseases. We quickly began to do what we could to help. Joe was by then producing for ’20/20’ and produced some of the earliest pieces to de-stigmatize this terrible disease. I did all I could through various organizations such as AIDS Action Council and God’s Love We Deliver.”

“We lost so many friends but never stopped our fight against HIV,” Cottrell added. “Our love for each other continued to blossom and we faced many challenges from Joe’s loss of vision and my lymphoma. Joe developed idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and progression was inevitable. In March we celebrated Joe’s 80th birthday with many friends and family members, all celebrating our 49 years together as a same-sex couple and his great achievement of reaching 80.” (Indeed, I remember Lovett throwing himself a big 50th birthday party because, he said, his own father had died at 50 when Lovett was 9 and his mother when he was 13 — and he figured early death might be his lot as well. The invitation read, “If I should live…”)

Lovett’s friend Ash Kotak, playwright and founder of AIDS Memory UK: The AIDS Memorial in London, said, “Joe and Jim inherited me in my 20s after my lover Nigel had died of an AIDS-defining illness. Staying with them at their Soho townhouse in 1995, I ventured out for a drink to a Christopher Street bar where a 30-something chap, I got chatting to, startled me when he snarled something like: ‘Look at these guys. Many are riddled with AIDS yet they dare come here looking to hook up.’ Feeling defeated and ashamed, I excused myself, sulked back home and recounted the story to Joe, who characteristically responded, ‘Why the hell didn’t you tell him you were positive?’ I had let myself and — even worse — Nigel down and I regretted it. Joe, noticing my further upset, softened: ‘You have to stick up for who you are, otherwise those who don’t want you to exist win!’”

“I never forgot that conversation,” Kotak said. “That was Joe. His brilliance gave me the space, the strength, and the safety to be myself. Our 30-year long friendship has been a journey of: education, exchanging ideas, and learning; mutual respect; creativity; true allyship and overall kindness, laughter, and fun. Joe forced out the absolute best in everyone in his life. He demanded that we all authentically be ourselves, whether we and — crucially — those who did not get it yet, liked it or not.”

A memorial service will be held sometime in the fall.

Cottrell described his late husband as a “remarkable person” who received “so many accolades that reminded me of why I loved him.”

“It will be hard to be without him,” Cottrell said.

The Joseph Lovett Papers are archived at NYU’s Fales Library.