“Titane” is determined to make David Cronenberg’s “Crash,” its biggest inspiration, look tame. Its vision embraces the ambiguous potential of queerness. Gender is fluid, barriers between human and machines have broken down. Its body-horror should be a logical extension of director Julia Ducournau’s short “Junior” and first feature “Raw.” Those films used genre tropes to convey the changes experienced by teenage girls and young women as they grow up.

By legend, one Toronto Film Festival passed out in shock at the gory cannibalism in “Raw,” although Ducournnau doubts this story’s truth. She tops the shock value of “Raw” within the first half hour of “Titane.” The scene where a woman’s hair gets caught in a pierced nipple will make most spectators squirm. But the film strains hard in its punk posturing, especially since its other influences — Shinya Tsukamoto’s “Testuo: Iron Man,” the 2000s New French Extremity movement — did this better.

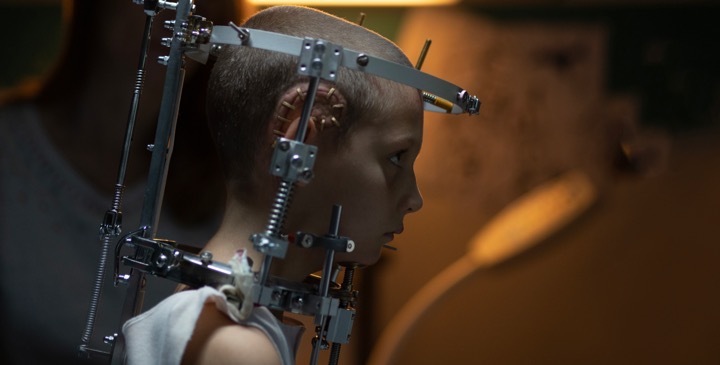

When Alexia (Agathe Rouselle) was a child, she survived a car accident caused by her father. But she required surgery to implant a titanium plate in her head. (“Titane” is the French word for the metal.) It still left her with permanent damage to one ear and a partially exposed brain. As an adult, she gyrates like a stripper at automotive shows, entertaining the spectators. She’s also a serial killer with a fetish for cars. After she has sex with a car, she becomes pregnant with its fetus, and her belly gradually expands. But her life takes a new turn when she decides to pose as Adrien, the grown son of Vincent (Vincent Lindon), who disappeared as a child a decade ago. She transforms herself into a man, hanging out with an ultra-masculine group of firefighters and becoming accepted by them.

“Titane” is loaded with nudity, none of it sexy. (Obviously, that’s a subjective judgment.) It might have been made to bring certain images to life, like Alexia scratching open a hole in her pregnant belly or leaking oil from her breasts. Her body was marked by the car crash in ways she couldn’t control. Her tattoos and piercings allow her to reclaim her own agency, but almost every time we see her naked body, it’s scratched up, or worse. At the car show, she’s performing to please men, but she tells off a fan who’s too bothersome. The film defies expectations about violence towards women (and their ability to commit it themselves.) As Peter Debruge wrote in a Variety review, “In a more traditional horror movie, a character like this, leaving the venue after everyone else, might wind up victimized — raped or stabbed by a lusty serial killer. But that’s not at all how the night plays out, and before long, Alexia has demonstrated that she can defend herself just fine.”

“Titane” flirts with recognizable emotions, while it keeps denying them. Despite its icy veneer, “Crash” was ultimately a story about genuine love tied to the death drive. Ducournau’s direction is deliberately garish, with exaggerated lighting and colors. The cinematography oozes neon sleaze. While “Titane” may go further than “Raw” in many respects, it lacks Ducournau’s earlier film’s ability to ground its flights of fantasy in a believable character going through a real struggle. The final scene of “Raw” adds up to more than the entire subplot between Vincent and Alexia.

“Titane” expresses something about father/child relations and chosen families. Masculinity is seen as a posture that even cis men have to work hard on. Vincent has destroyed his buttocks with ugly bruises caused by injections, probably of steroids. But once Alexia shaves her head and binds her breasts, she’s accepted as male despite her pregnant belly. By the end, Vincent realizes that she’s probably not his son, but gets something out of their relationship anyway. The problem is that “Titane” is so impressed with its own transgressions that it forgets what it’s doing with such extreme metaphors. The emotional bond between Vincent and Alexia plays second fiddle to images of her body covered in scratches and scars.

TITANE | Directed by Julia Ducournau | Neon | In French with English subtitles | Opens Oct. 1st at AMC Theatres