Hundreds of queer people and allies gathered in Manhattan on June 28 to celebrate Harlem Pride’s “sweet 16,” filled with dancing, bright colors, and tributes to the historic neighborhood’s visionary leaders both past and present.

“Pride means a time when we get to express ourselves, a time when the community gets to come together,” Carmen Neely, co-founder and CEO of Harlem Pride, told Gay City News. “It’s a time to be lighthearted, leaving the cares behind and just enjoy being in the moment.”

In 2010, Neely and Lawrence Rodriguez co-founded Harlem Pride, which takes place on the fourth Saturday of June on 12th Avenue between West 130th and 132nd Streets. Since then, the annual tradition has only grown larger and more inclusive, she emphasized, and it’s the perfect opportunity to bring together people of different identities within the LGBTQ community, and to share resources with them.

Neely is motivated by “the joy that we see on the young people’s faces, that they know there’s something that … they can feel affirmed by.” Harlem Pride, she said, is “historical, it’s cultural, it’s all things Black, all things Brown, and it’s a different cultural spin than larger society in New York City.”

Many queer people partook in the Harlem Renaissance, Neely said, “so we’re like the rebirth of that here in the 2000s.”

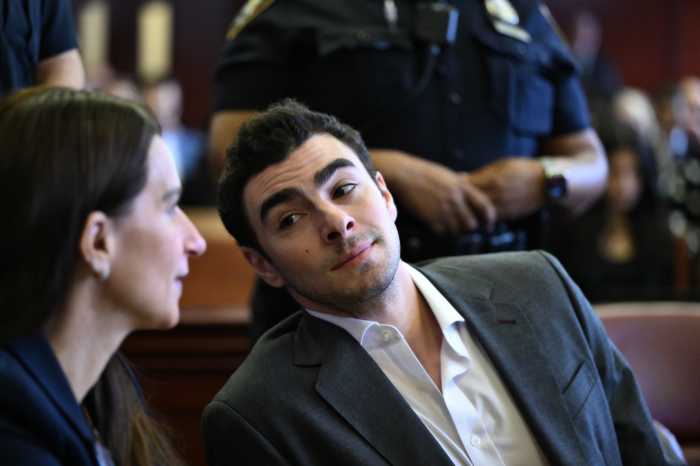

Over the past decade and a half, Harlem Pride has strengthened its ties with other non-profits, city agencies, and local elected officials, Neely said, like Harlem Assemblymember Jordan Wright, New York Attorney General Letitia James, and Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg, who all stopped by the festival.

Wright, an LGBTQ ally, recalled his father, former Assemblymember Keith Wright, bringing him to his first Pride celebration in 2005.

“I’ve got a lot of work to do in the New York State Assembly making sure gender-affirming care is always there, making sure that we are always, always, always on the right side of history,” Wright said.

Underneath the shade of the 12th Avenue Viaduct, the festival featured resources, free HIV and STI testing, and games with the public. Vendors included local and citywide organizations like ACT UP, The LGBT Center, and Ryan Health Center, along with city agencies like the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. A local restaurant, Dinosaur Bar-B-Que Harlem, fed the crowd complementary chicken sliders.

At the Studio Museum in Harlem’s table, the public paid tribute to queer ancestors from the Harlem community by creating collages with the images of deceased famous and little-known LGBTQ Harlemites, inspired by the AIDS memorial quilt and artist Faith Ringgold’s quilt, “Echoes of Harlem.”

“There’s always been queer people, there’s always been trans people in Harlem,” said Madison Smith, who works for the museum, “and I love reflecting on who walked these streets centuries ago.”

Smith highlighted the story of Mary Jones, one of the first Black trans women documented in New York City history, through an 1836 court case.

The Museum is planning to open this Fall, after a seven-year closure.

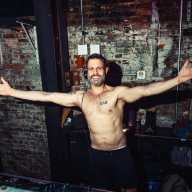

The scorching late-June sun didn’t stop people from gathering in front of the main stage, where hosts, actor Jerrie Johnson and “plant kween” Christopher Griffin introduced performers from far and wide.

Midway through the celebration, Neely presented “legacy of pride” awards to three local leaders: Nala S. Toussaint, an award-winning speaker and policy advocate; Vanessa Miller, a Jamaican-born psychologist and wellness consultant; and Dr. George Dawson, MD, who Neely said provided the community with vital resources during the COVID pandemic and mpox outbreak.

“You are sacred, you are worthy, you are not too much, your joy is not too much,” Toussaint told a crowd, reminding them that “each breath you take is a form of liberation.”

Striking a more somber note, she added, “We’re gathered today here full of light, but cannot ignore the shadow. Our transgender siblings are under siege, in Congo, in Palestine, in Sudan, in prisons, on the streets, in churches, and yes, sometimes even in our own homes.”

Gay City News asked festival goers what Pride — and Harlem Pride specifically — means to them.

Toniee Harris, a Harlem native, came to the festival in a bright-colored dress with a rainbow flower crown to represent queer lesbians.

“Pride to me is being yourself, showing up authentic, and not caring [about] nobody’s opinions of you,” Harris said. Celebrating in Harlem “is a wonderful feeling, because for somebody like me who grew up here, I had to go all the way to the Village to have a good time.”

“Pride means inclusivity, diversity, [and] happy people,” stated Dariel, with her partner AJ, who added, “It’s common sense, just be.”

Queen, who told Gay City News she has attended every Harlem Pride festival since the tradition began, described Pride as “unity, respect and love,” adding that “Harlem Pride means Black community and respect.”

Pride means “someone being proud they can be whoever they want, they don’t have to hide,” said Vernita Paige, a Harlem native and queer ally.

Niyya Tenee came to Harlem Pride for the second year in a row, wearing a rainbow dress.

“It’s so important to be able to feel accepted and loved by your community,” Tenee said. “Specifically in Harlem, as an African-American who’s a native New Yorker, Harlem has such a rich history, so to be able to be home in your own neighborhood, fully embodied as yourself, fully accepted, celebrated — that’s really special.”