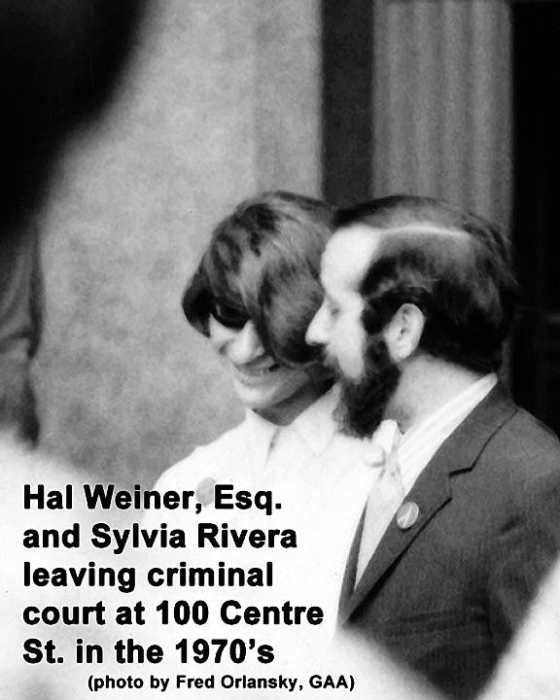

In 1971, Hal Weiner, who died July 9 at age 90, was a young attorney representing sex workers in court in New York City when one turned out to be Sylvia Rivera. But In this case, Rivera told him, she was soliciting in Times Square not for johns but for signatures supporting the nation’s first gay rights bill promoted by the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) that had been formed the year before in the wake of the Stonewall Rebellion.

Members of GAA and the Gay Liberation Front packed the courtroom, and when Weiner understood Rivera’s case as a First Amendment issue, he successfully moved to have it dismissed.

While Weiner had no previous relationship with gay issues or the gay community, he knew injustice when he saw it and agreed to be retained as the counsel for GAA, thereafter representing the group’s members when they were arrested at their famous “zaps” — demonstrations where they took over the offices of offending companies, agencies, and newspapers. He also represented them when arrested for cruising publicly.

Weiner also won an epic court battle to win GAA’s incorporation from the State of New York. He even got State Attorney General Louis Lefkowitz on the phone, only to be told that “buggers” would be certified over his dead body. Even the word “gay” in the title was cited as an impediment by the New York State Division of Corporations and State Records. Weiner sued the state. It took five years and several appeals, but he won.

At the first City Council hearing on the gay rights bill in 1971, Weiner testified “as a lawyer, a citizen, and a parent,” saying the bill was “a small step for homosexuals and a giant step for Homo Sapiens,” the newspaper GAY reported. (That hearing attracted a stellar lineup of witnesses for the legislation, including Mayor John Lindsay; Congressmembers Bella Abzug, Shirley Chisholm, Herman Badillo, and Ed Koch; Episcopal Bishop Paul Moore; Rabbi Balfour Brickner; labor leaders Victor Gotbaum and Stanley Hill; Human Rights Commissioner Eleanor Holmes Norton, now in Congress; NYCLU director Ira Glasser; NY Times theater critic Clive Barnes; and feminist leader Kate Millet. But the right-wing leadership of the Council blocked the bill and it did not pass until 1986.)

Rich Wandel, who was the second President of GAA, said, “I remember Hal Weiner as simply someone who was there, quietly doing his part. Rather a subdued presence by lawyer standards. With a few notable exceptions, arrests were always planned ahead of time and determined by the number of volunteers and amount of available funds. Hal was simply there, taking care of things, usually resulting in ACDs [acquittals contemplating dismissals].” He noted Weiner’s “importance to GAA and the movement at that time. He is well deserving of our recognition and gratitude.”

Longtime gay activist Steve Ashkinazy remembers him a little differently. “Not everyone realizes what a frequent presence he was at The Firehouse [GAA’s community center in Soho], attending meetings and being a vocal participant at them. He often offered his opinions and advice about ongoing developing policies and strategies. He also made some important first-time introductions to political figures who would eventually become supporters. It always came as a surprise to people when they learned that he was not gay. He never offered that information, himself. But it was a regular part of The Firehouse gossip. Someone would point and say, ‘See that guy over there? He’s not gay,’ to which the incredulous hearer would respond, ‘Then what’s he doing here?’ The short answer was, ‘He volunteers as our lawyer.’ I don’t believe we were using the word ‘ally’ yet, but he was definitely the first ally that I ever knew.”

Bill Bahlman, who had been chair of GAA’s National Gay Movement committee in the early 1970s, told Gay City, “Hal Weiner was a dedicated lawyer for GAA. When our members needed a lawyer from an arrest at an action, Hal would show up at The GAA Firehouse and community center often in a full length fur coat. His dedication impressed me, often arriving late into the evening. As an early straight ally, he never once felt the need to say, ‘I’m not gay.’ He was our lawyer and a damn good one too.”

At the behest of Marsha P. Johnson, Weiner also represented STAR (Street Transvestites Action Revolutionaries), the group Johnson founded with Rivera, the first group to work for trans rights.

Veteran gay activist Mark Segal, a participant in the Stonewall Rebellion, related in an interview with Out in NJ last year how Weiner defended him in court when he and another member of a group called the Gay Raiders were arrested for zapping CBS Evening News anchorman Walter Cronkite during a live broadcast in 1973 to protest a lack of LGBTQ coverage.

Segal recalled that Weiner said to the CBS lawyers, “‘We’re going to subpoena Walter Cronkite.’ They said, ‘No, you’re not, Walter’s too busy.’ He said, ‘Well, if you don’t allow me to just come through the doors and do that, I’m going to Xerox one hundred copies of the subpoenas and give them out to Gay Liberation Front members and Hells Angels of New York and offer a $1,000 bounty for Walter.’ Well, he walked into the doors of CBS the following morning and served Walter.” Segal got off with a $200 fine and subsequently forged a close bond with Cronkite in journalism.

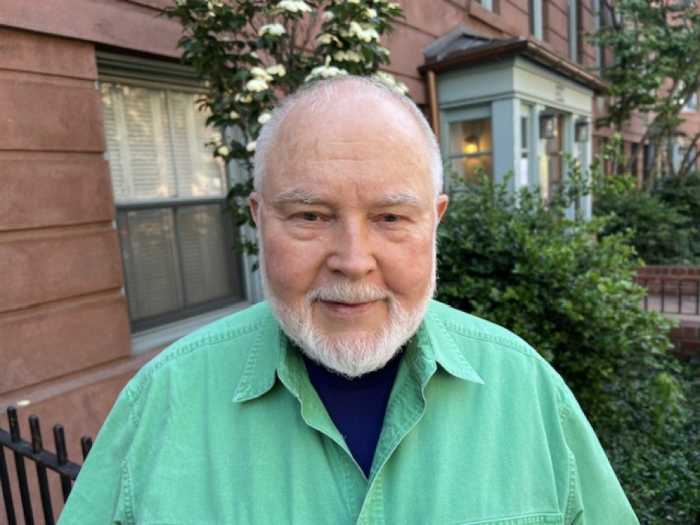

Weiner is survived by his wife, Phyllis J. Murray, five children, and five grandchildren.

A funeral will be held Aug. 16 at St. Christopher’s Episcopal Church, 116 Lancaster Pike, Oxford, Pennsylvania. Visitation will be at 10:30 a.m., with the service at 11 a.m. Repast to follow.

A second funeral mass with interment of ashes will be held on Oct. 11 at 11 a.m. in the Great Choir at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, 1047 Amsterdam Avenue, New York, NY. Reception to follow at Cathedral House.

Hal Weiner spoke about his life in an extensive interview for the Stonewall History Project on video here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9M0Gt93zKr4