A dear friend of mine, a mature yet still very young gay man, died two weeks ago. It happened suddenly and he hadn’t had the opportunity to put the smaller details of his affairs in order. Amid the shock and devastation we in his close circle of friends and chosen family are experiencing, a question recurs: What about the personal items and files he would have liked removed from his home before his next of kin, people who loved but knew him as someone else, could run across them? It’s not that he was closeted. The intention was to honor in death the compartmentalized selves our friend maintained in life. He’d mentioned it, mostly in jest, while he was alive — a padlocked suitcase one of us would be instructed to spirit away; a safety deposit box bearing the campy nickname he was dubbed one summer on Fire Island as its combination. No, the circumstances of his sudden death now mean the divisions he put up between his different selves are fated to come down, soon and very soon.

Few people evade such posthumous exposure. But, the will to keep intact the architecture of a dearly departed’s life is strong — even, or especially, when the loved one served the public in some open and lasting way that stokes interest in the trail they left behind. The writer James Joyce’s grandson, Stephen Joyce, kept a firm grip on the deceased author’s estate, thwarting biographers’ desperate attempts to access the author’s letters and diaries to better understand what drove him.

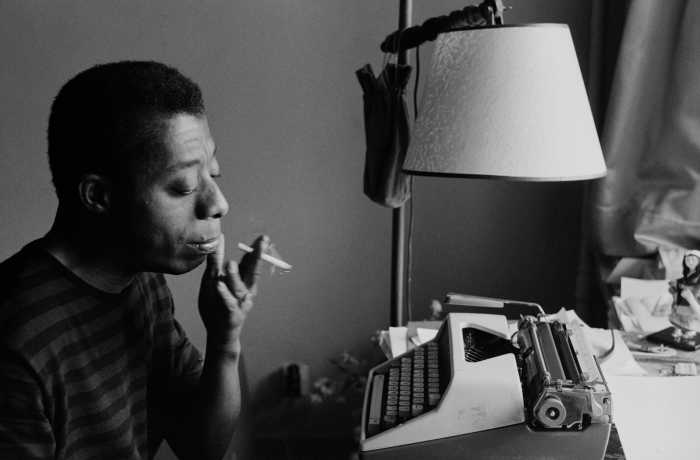

“The Plural of He” is a group exhibition on view at Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art until July 21 that strikes at the heart of this impulse. It seeks not to block people from the archive of a fallen figure — the activist and writer Colin Robinson (1961-2021) — but immerse them in it. Curator Andil Gosine, executor of Robinson’s lifelong media estate, invited five visual artists working in a range of media to create works in reaction to writings and personal effects of the man lauded as a godfather of the LGBTQIA+ movement by many of his fellow activists. The archive stretches as far back as the 1970s, with poems Robinson penned as a self-accepting gay boy in his country of origin, Trinidad and Tobago, and extends to the very last email he sent in 2021, while battling cancer in Washington, DC. The title of the exhibition is taken from one of Robinson’s poems published in his 2016 collection, “You Have You Father Hard Head.”

“The show is meant to mimic the experience of getting to know someone,” Gosine said. The artists had all participated in a residency at Leslie-Lohman during which they were encouraged to forge connections among themselves as well as with the archive.

Devan Shimoyama’s contribution, “Porky was loud,” is a shimmering, colorful portrait of a hefty man letting himself go to the beat of a tune from somewhere in the environment. He is a collage of materials, patterns and moods, part drawn, part painted, part appliquéd, sequined, and glittered. The surrounding installation is a familiar scene from yesteryear: an eighties-looking red Formica kitchen table with two chairs on tiled flooring in a gaudy pattern of loud colors identical to the portrait’s backdrop. Atop the table sits a mini boom box and a hard copy of the title page of “Porky’s was Loud,” an unfinished novel by Robinson. Welcome to Brooklyn in the 1980s, the place where Robinson landed after dropping out of Yale after just one semester and coming to join the community of Black queer writers he had sent letters of introduction from Trinidad. In this Twilight Zone-esque portrait and installation, Shimoyama transports the visitor in not only space and time, but dimension, transmuting a piece of Robinson’s creative imagination into a personification.

Leasho Johnson’s piece, “The shrinking world (Anansi #25),” is a beautiful watercolor tableau of lush tropical flora engulfing a four-door automobile whose doors look missing. Was the vehicle abandoned or vandalized? Are there people inside or is it the swirl of plant life that’s overtaken the interior? Is this a scene of crime or decay? Johnson’s inspiration came from op-ed articles Robinson published in the Trinidad and Tobago newspaper Newsday in the mid 2000s after returning to the island-nation and co-founding a queer advocacy organization, CAISO (Coalition Advocating for the Inclusion of Sexual Orientation). Running through those articles, Gosine noted, is the theme of homophobic violence, which Johnson connected to cases in his native Jamaica of queers getting assaulted, sometimes fatally, in their own homes and cars. The message: your car might be the only private place to make out with your lover, but you might end up dead in it if the wrong person spies you.

A mood of dissection characterizes Ada Patterson’s series of close-up drawings of hands, objects and shapes, “a piece of you no one else will have.” Its title a line from Robinson’s poetry, the series captures a yearning the poet expresses to be the only one to whom a beloved, real or imagined, entrusts a delicate part of himself. In one drawing, a hand holds a black circle up against a backdrop of twinkling sea, fire-red sky and white cloud formation, a world that can exist only in the imagination. As Gosine writes in one of several testimonial wall texts that intersperse the art, “Of the many, many treasures unearthed from Colin’s archives, the ones that touch me most bear the weight of love: a mixtape he made for his beloved Kodjoe; letters to ones that could have been but were decidedly not; and, most achingly, dozens of unwritten ‘dear sweetheart’ cards he collected over decades to gift to a lover that did not come.”

To create her collage portrait, “Another Poem,” Llanor Alleyne engaged with both Robinson’s poetry and a now-iconic photograph of him shot in 1988 by the photographer Robert Giard. Alleyne made a silhouette of the unmistakable pose Robinson struck for Giard’s camera, placed it at the center of her own canvas, and encircled it with a rich tapestry of flowers in bloom. The effect is simultaneously joyful and somber.

Natalie Wood turned to costumes from Trinidad’s world-famous Carnival, enthusiasm for which Wood, who also spent her youth in Trinidad, shares with Robinson. Her installation, “Great Bernadine Royal Cobo of the Caribbean,” features an all-black, feathered costume whose style references the classic crow masquerade costumes of the Venice Carnival, but is disruptively accessorized with a hot-pink hockey stick. Wood migrated to Canada at roughly the same time Robinson moved to New York and the piece speaks to the dislocation they both negotiated. A video of her performing in the ensemble runs on the wall.

Rounding out the show are works created by two artists who had not been part of the internship project: Richard Fung’s video-based performance piece, “Untitled (For Colin)” and Amber Williams-King’s “Godfather’s return” (co-created with Andil Gosine), a textile wall hanging that incorporates a photograph of Robinson in dance mode at a Carnival fete (party) in Trinidad, not too long before his cancer diagnosis.

“The Plural of He” | Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art | Until July 21, 2024

Nicholas Boston, Ph.D., is a professor of media sociology at Lehman College of the City University of New York (CUNY).