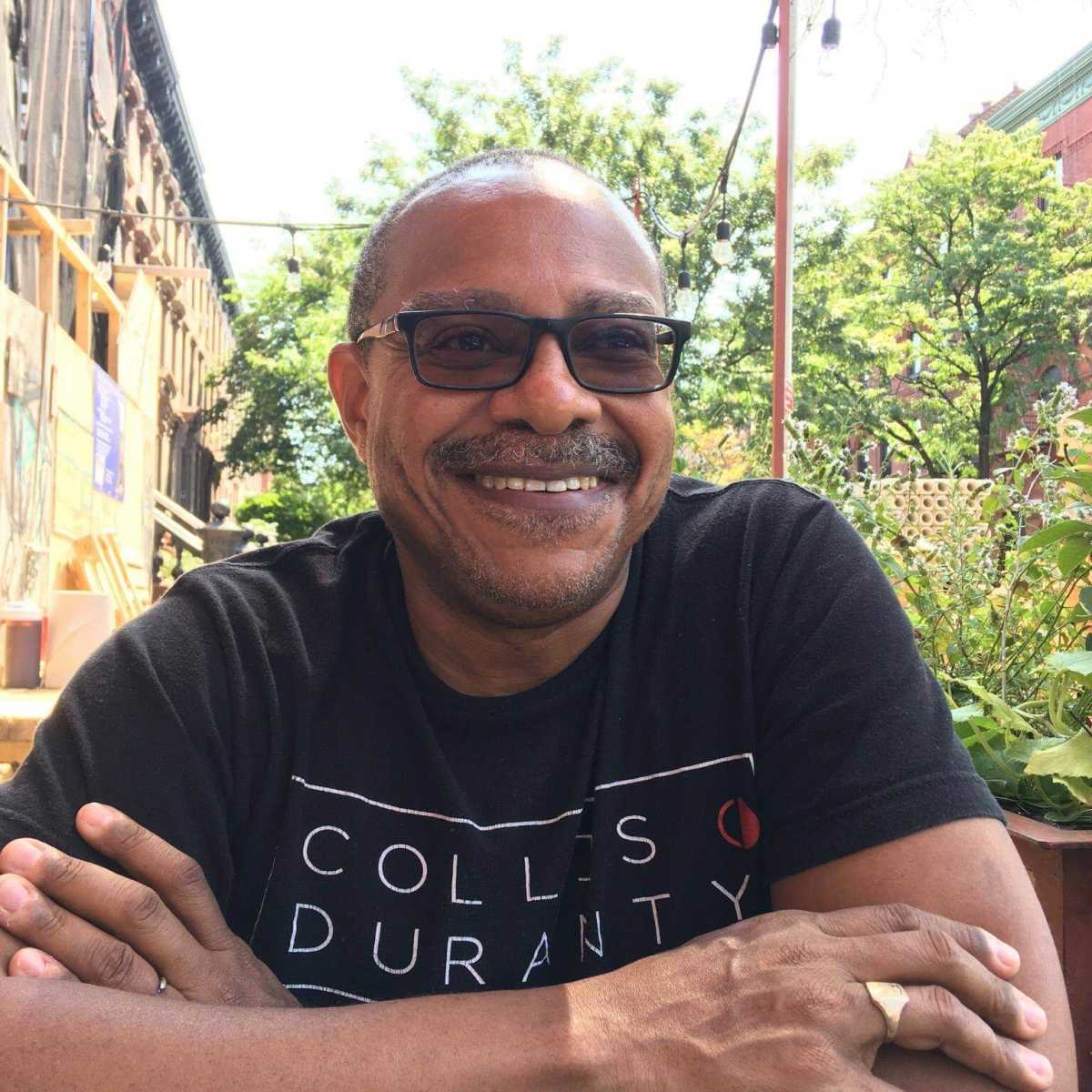

Friends and family of Colin Robinson, an activist, organizer and writer who passed on March 4 in Washington, DC, at age 58 from cancer, gathered virtually on March 28 to celebrate his life and honor his contributions.

Entitled, “Life Portrait and Libations,” the two-hour memorial convened Colin’s loved ones across multiple locations — the Caribbean, Canada, the United Kingdom, the United States, and beyond.

Colin was originally from Trinidad & Tobago. He lived in New York City from 1980 to 2007, and throughout that period stood at the forefront of LGBTQ+ organizing. He was a co-founder and/or executive director of GMAD (Gay Men of African Descent), the Audre Lorde Project, the New York Black Gay Network, and Caribbean Pride. He held executive positions and board memberships at pillar organizations such as Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) and Center for LGBTQ Studies (CLAGS). Colin’s organizing always prioritized coalition-building politics and solidarity, and he worked across identities and struggles.

In 2007, Colin decided to move back to Trinidad, where he continued his LGBTQ+ human-rights work, in 2009 co-founding the Coalition Advocating for the Inclusion of Sexual Orientation (CAISO) (renamed “CAISO: Sex and Gender Justice” in 2016), and serving as its executive director until his passing. It was in large part through CAISO’s tireless advocacy that the government of Trinidad & Tobago decriminalized homosexuality in 2018. Colin resolutely rejected “any fetishizing of the Caribbean region as some homophobic, backward place it is not,” he told me by text in 2015.

In 2016, Colin published a collection of poetry, “You Have You Father Hard Head” (Peepal Tree Press), an offering of verse he had been sharing on multiple platforms — edited volumes, film, spoken word — for decades.

Colin belonged to that generation of Black gay men besieged by AIDS in the 1980s and ‘90s that produced a flowering of poetry and prose, film, community spaces and organizations to bring Black gay identities out of invisibility. He was amongst the subgroup of these men whose activism and creative labor coalesced around the work of Marlon Riggs, and it was through those productions that I first became acquainted with Colin before I even met him. In Riggs’ short films, “Affirmations”(1990) and “Anthem” (1991), I saw Colin’s mouth and heard his voice.

In “Affirmations,” Colin’s voice is part of a symphony of Black gay men vocalizing the things they wish to have and be. “First openly gay, Black talk show host with a…openly gay talk show,” Colin says in a sultry tone.

In “Anthem,” Colin’s lipsticked mouth is the star, and his poetry showcased. Riggs’ camera zeroed in on Colin’s lips and tongue as they form the words of the poem, “Unfinished Work.” The footage is cut up and the lines of the poem shuffled and remixed:

Pervert the language

Parade it proudly

Flaunt it like a man

I am afraid of forgetting our language

No immunity in this procession of dying

Griots shaping language into power, food, and substitute for sex into tools like weapons of

survival, rage and passion with the clarity of spit.

When I first moved to New York in 1994, I met the man attached to that mouth. I don’t remember exactly when and where. In my memory, he was always there, always offering mentorship in his understated, it’s-up-to-you way.

But, I quickly learned, don’t ask Colin for advice unless you are fully prepared to swallow the undiluted truth. Aware of his grantsmanship, I once asked him to look over a statement I’d written for a grant application I was submitting. He took the paper from me and I watched his eyes scanning the saccharine narrative I’d composed, his brow furrowing and that full mouth of his twisting. He looked up at me and said, “Is this for real?” I was speechless. Colin didn’t wait for an answer. He attacked the page with his pen, crossing out line after line and jotting down instructions on how I was to restate my intentions in language addressing a funder, not a friend.

That fall, I found myself temporarily between apartments. Colin and his housemates, with whom I had also become friends (I respect folks’ right to celebrate, mourn and reflect privately, so I mention no names, but you know who you are), invited me to stay a few days at their townhouse in Fort Greene, Brooklyn. They had an unwritten policy that their home be a space of welcome for Black LGBTQs. My few days turned into a few weeks. The housemates, professional advocates, travelled a fair bit for work, and they kindly let me stay in their rooms while they were away.

When the house filled up again, Colin said I should just sleep in his bed. He had a king-sized bed with lots of space for two people, and the bedroom itself was spacious, with large windows facing the quiet, tree-lined street. Several evenings, as we were lying or sitting up in bed, we talked about stuff, both heavy and light, from personal confessions to folklore to advocacy work, the subject never too far from Colin’s consciousness.

One time, we got into a conversation about scary West Indian legends, comparing the differences between how (or if at all) they were recounted in my Guyanese versus his Trinidadian folkloric tradition. We talked about “soucouyant” (Trinidad)/”Ole-Higue” (Guyana) — the old woman who sheds her skin after nightfall and travels as a ball of light to suck the blood of sleeping humans. And about “La Diablesse” (pronounced Zsa-bless), a demon in Trinidadian lore who appears to men as a beautiful, alluring woman on deserted roadsides at night, wearing a long white dress under which is one human foot and one hoof. Colin was such a passionate storyteller that even big-big me, I felt a chill up my spine. And then, since he always fell asleep first, there he was, snoozing peacefully beside me, as I lay wide awake, clutching the blanket to my neck, frightened to hear Diablesse’s hoof coming up the stairs.

Bookcases lined Colin’s bedroom walls. During one of our nighttime chats, he explained that he arranged his books by category, not author’s surname. The categories don’t readily jump to mind now — this was almost 30 years ago — but I recall one was “Black Feminism,” and, educational to me at the time, “Radical White Woman Allies” another. The latter was a very small section — only about four or five books — and in it was where I read the name “Mab Segrest” for the first time. “Memoir of a Race Traitor: Fighting Racism in the American South” had been published earlier that year. Like his mentorship, Colin’s pedagogy was omnipresent — it happened all around you, if you were ready to receive it.

The list of activists, cultural producers, scholars and organizers who passed through that house in Fort Greene to visit and consult with Colin is now a Who’s Who of LGBTQ community-building, critical inquiry and creative expression — not just New York-based, but national and international. It was there that the first planning meetings and social gatherings for what became the multiracial Caribbean-identified Lesbian and Gay Alliance (CiLGA) were held.

CiLGA was the first Caribbean queer organization to march in a New York Pride parade, Stonewall 25, in 1994. Colin was front and center, proudly holding a big Trinidad & Tobago flag up high. Later that year, CiLGA members attended the Brooklyn West Indian-American Labor Day Carnival, possibly another first for a queer collective, distributing leaflets about the organization and HIV/AIDS awareness and prevention.

When I became a reporter for this newspaper in 2003, I often found myself reporting on Colin Robinson’s activism and initiatives. By that time, Colin was serving as executive director of the New York State Black Gay Network, protesting racism in the LGBTQ community, homo/transphobia in Caribbean-diasporic and BIPOC communities, and both within the general public. His work was not only coalitional, it was patient.

“I mean, if you’re an activist like me, categorizing someone as a homophobe is reductionistic,” he once wrote to me. “Everyone has the potential to do homophobic things or to grow into new awareness. ‘Zero tolerance’ is such shit.”

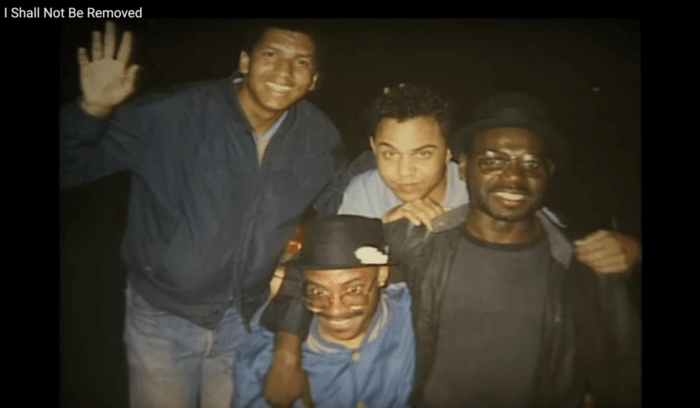

One of the last pieces of advice Colin gave me was in December, 2020. I showed him the photo below of him from the early ‘90s in the loving embrace of Marlon Riggs and other community members. I thanked him for his contributions — to me and to the community.

“Ah,” Colin responded. “Look forward.”

The fee for this article is donated to the “Colin Robinson Hard Head Award.” Kindly consider making a donation to this fund here.

Nicholas Boston, Ph.D., is an associate professor of media studies at Lehman College of the City University of New York (CUNY), and author of “The Amorous Migrant: Race, Relationships and Resettlement” (Temple University Press).