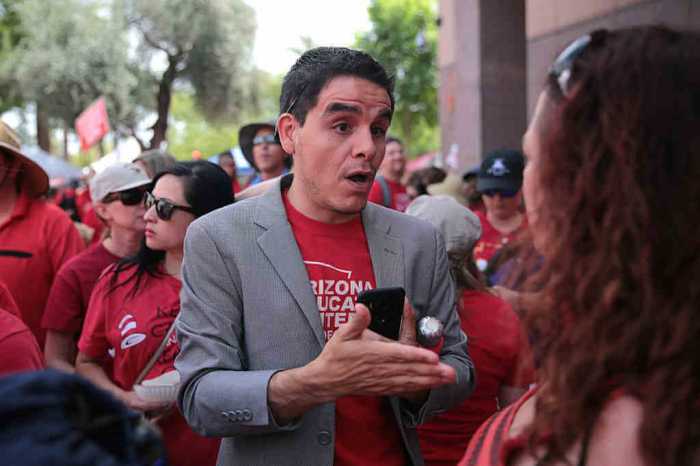

Judge Lawrence F. Winthrop. | CALIFORNIA WESTERN SCHOOL OF LAW

The precedent established by a Supreme Court decision can often depend on how lower courts interpret it. The quick takeaway from last week’s Masterpiece Cakeshop ruling was that it was a “win” for baker Jack Phillips, since the court reversed the discrimination rulings against him by the Colorado Court of Appeals and that state’s Civil Rights Commission.

But the nuances of that opinion go beyond what a superficial call of “win” or “loss” can capture, as the Arizona Court of Appeals demonstrated just days later in rejecting a claim that a company that designs artwork for weddings can refuse to provide goods for same-sex weddings.

Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF), the same anti-LGBTQ legal outfit that represented Phillips before the Supreme Court, represents Brush & Nib Studio, a Phoenix, Arizona company that sells both pre-fabricated and specially designed artwork. Because it provides retail goods and services to the public, it comes within the purview of Phoenix’s public accommodations anti-discrimination ordinance.

State appeals panel finds no free speech, religious exercise basis for rejecting gay wedding business

Brush & Nib went to court without ever having received a request to produce invitations for a same-sex wedding. Instead, it owners concluded that because of their religious beliefs they would not provide such services and, represented by ADF, sued in the state trial court seeking a preliminary injunction to bar enforcement of the ordinance against them in case any such customers come knocking.

As described in Judge Lawrence F. Winthrop’s opinion for the Court of Appeals, Brush & Nib’s owners “believe their customer-directed and designed wedding products ‘convey messages about a particular engaged couple, their upcoming marriage, their upcoming marriage ceremony, and the celebration of that marriage.’” Their suit asserted they “also strongly believe in an ordained marriage between one man and one woman, and argue that they cannot separate their religious beliefs from their work. As such, they believe being required to create customer-specific merchandise for same-sex weddings will violate their religious beliefs.”

The owners not only sought assurance they could reject such business without risking legal liability, they also wanted to post a public statement explaining their religious beliefs, including a statement that they would not create any artwork that “promotes any marriage except marriage between one man and one woman.” To date, they have not posted that statement out of concern they might violate the Phoenix ordinance.

Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Karen Mullins rejected their motion for preliminary injunction, finding that the business did not enjoy a constitutional exemption. The Court of Appeals, meanwhile, held up ruling on ADF’s appeal until the Supreme Court issued its Masterpiece Cakeshop decision on June 4, then quickly incorporated references to it into Winthrop’s opinion issued on June 7.

Winthrop reviewed the unbroken string of state appellate court rulings from around the country that have rejected religious and free speech exemption claims in cases of this kind over the past several years, and he wrote, “In light of these cases and consistent with the United States Supreme Court’s decisions, we recognize that a law allowing Appellants to refuse service to customers based on sexual orientation would constitute a ‘grave and continuing harm’” — that last phrase drawn from the Supreme Court’s 2015 marriage equality ruling.

Winthrop continued with a lengthy quote from Justice Anthony Kennedy’s opinion in the Masterpiece Cakeshop case: “Our society has come to the recognition that gay persons and gay couples cannot be treated as social outcasts or as inferior in dignity and worth. For that reason the laws and the Constitution can, and in some instances must, protect them in the exercise of their civil rights. The exercise of their freedom on terms equal to others must be given great weight and respect by the courts. At the same time, the religious and philosophical objections to gay marriage are protected views and in some instances protected forms of expression… Nevertheless, while those religious and philosophical objections are protected, it is a general rule that such objections do not allow business owners and other actors in the economy and in society to deny protected persons equal access to goods and services under a neutral and generally applicable public accommodations law.”

That portion of Kennedy’s opinion then cited two Supreme Court cases, which Winthrop took note of, that evidently sent a strong message for lower courts. Newman versus Piggie Park Enterprises, from 1968, is a classic early decision under the 1964 Civil Rights Act, holding that a restaurant owner’s religious opposition to racial integration could not excuse him from serving people of color.

In contrast, in Hurley v. Irish–American Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Group of Boston, from 1995, the Supreme Court upheld that city’s St. Patrick’s Day Parade organizers’ First Amendment right to exclude a gay Irish group from marching under their own banner. There, the court found that the parade was not a business selling goods and services, but rather a non-profit group organized for expressive activity whose organizers had a right to determine the content of their expression.

In other words, states and municipalities can forbid businesses from discriminating against customers because of their sexual orientation, and businesses with religious objections will generally have to comply with the non-discrimination laws.

The “win” for baker Jack Phillips involved something else entirely: the Supreme Court’s perception that Colorado’s Civil Rights Commission did not give Phillips a fair hearing based on the evidence of public statements by two of its members denigrating his religious beliefs. Kennedy found that a litigant’s dignity requires that a tribunal deciding his case be neutral and not overtly hostile to his religious beliefs, and that was the reason for reversing the Colorado state court and a state agency there. Kennedy’s discussion of the law itself, however, clearly pointed in the other direction, as Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg observed in her dissent.

The Arizona Court of Appeals clearly got that message.

Judge Winthrop rejected ADF’s free speech argument, writing, “Appellants argue that [the ordinance] compels them to speak in favor of same-sex marriages. We disagree. Although [it] may have an incidental impact on speech, its main purpose is to prohibit discrimination, and thus [it] regulates conduct, not speech.”

Winthrop pointed to Rumsfeld v. FAIR, from 2006, where the Supreme Court rejected a free speech challenge by an organization of law schools to a federal law requiring them to host military recruiters even though the Defense Department at the time discriminated against gay people. The law schools claimed that complying with the law would violate their First Amendment rights, but the high court said that the challenged law did not limit what the schools could say, rather what they could do — that is, conduct, not speech.

“We find Rumsfeld controlling in this case,” wrote Winthrop. “Like Rumsfeld, [the ordinance] requires that places of public accommodation provide equal services if they want to operate their business. While such a requirement may impact speech, such as prohibiting places of public accommodation from posting signs that discriminate against customers, this impact is incidental to properly regulated conduct.”

The court, further distinguishing this case from the Boston St. Patrick’s Day ruling, found that Brush & Nib’s creation of merchandise for same-sex weddings does not qualify as expressive conduct.

“The items Appellants would produce for a same-sex or opposite-sex wedding would likely be indistinguishable to the public,” Winthrop wrote. “Take for instance an invitation to the marriage of Pat and Pat (whether created for Patrick and Patrick, or Patrick and Patricia), or Alex and Alex (whether created for Alexander and Alexander, or Alexander and Alexa). This invitation would not differ in creative expression. Further, it is unlikely that a general observer would attribute a company’s product or offer of services, in compliance with the law, as indicative of the company’s speech or personal beliefs. The operation of a stationery store — including the design and sale of customized wedding event merchandise — is not expressive conduct, and thus, is not entitled to First Amendment free speech protection.”

Turning to the free exercise of religion issue, the court rejected the argument that requiring the business to provide goods and services for same-sex weddings imposed a substantial burden on the business owners’ religious beliefs, despite the owners’ claim that it could “decrease the satisfaction” with which they practice their religion.

“Appellants are not penalized for expressing their belief that their religion only recognizes the marriage of opposite sex couples,” wrote Winthrop. “Nor are Appellants penalized for refusing to create wedding-related merchandise as long as they equally refuse similar services to opposite-sex couples. [The ordinance] merely requires that, by operating a place of public accommodation, Appellants provide equal goods and services to customers regardless of sexual orientation.”

Brush & Nib’s owners could stop selling wedding-related goods altogether, but what they “cannot do is use their religion as a shield to discriminate against potential customers,” Winthrop wrote.

The city of Phoenix, the court concluded, “has a compelling interest in preventing discrimination, and has done so here through the least restrictive means. When faced with similar contentions, other jurisdictions have overwhelmingly concluded that the government has a compelling interest in eradicating discrimination.”

The court quoted from the Washington Supreme Court’s decision in the Arlene’s Flowers case a religious opt-out claim by a florist was rejected, but it could just as well have been quoting Justice Kennedy’s language in Masterpiece Cakeshop.

A spokesperson for ADF promptly announced the group would seek review from the Arizona Supreme Court. Whether or not that court accepts the case for review, ADF must take that step prior to petitioning the US Supreme Court, where it is clearly determined to bring this issue once again. The group also represents Arlene’s Flowers, whose petition to the Supreme Court is now pending, as well as a Minnesota videography company that, like Brush & Nibs, is affirmatively litigating to get an injunction to allow the company to expand into wedding videos without having to do them for same-sex weddings. A district court’s ruling against that company is now on appeal in the Eighth Circuit. One way or another, it seems likely that this issue will get back to the Supreme Court before too long.