The Metropolitan Opera concluded its “Ring Cycle” with a “Götterdämmerung” (seen April 27 at the matinee season premiere), which consolidated the strengths of its performers for a triumphant finale. Philippe Jordan’s conducting improved with each opera — the clarity and forward-moving lyricism of his interpretation were a constant. After a sloppy “Das Rheingold” and an uneven “Die Walküre,” Jordan found his footing with a vibrant reading of “Siegfried.” “Götterdämmerung” highlighted the maestro’s narrative abilities: Jordan’s storytelling was masterful, using orchestral color and detail to illuminate the action and create drama. There have been more profound, epochal interpretations of Wagner’s opus, but this one had consistent life and energy.

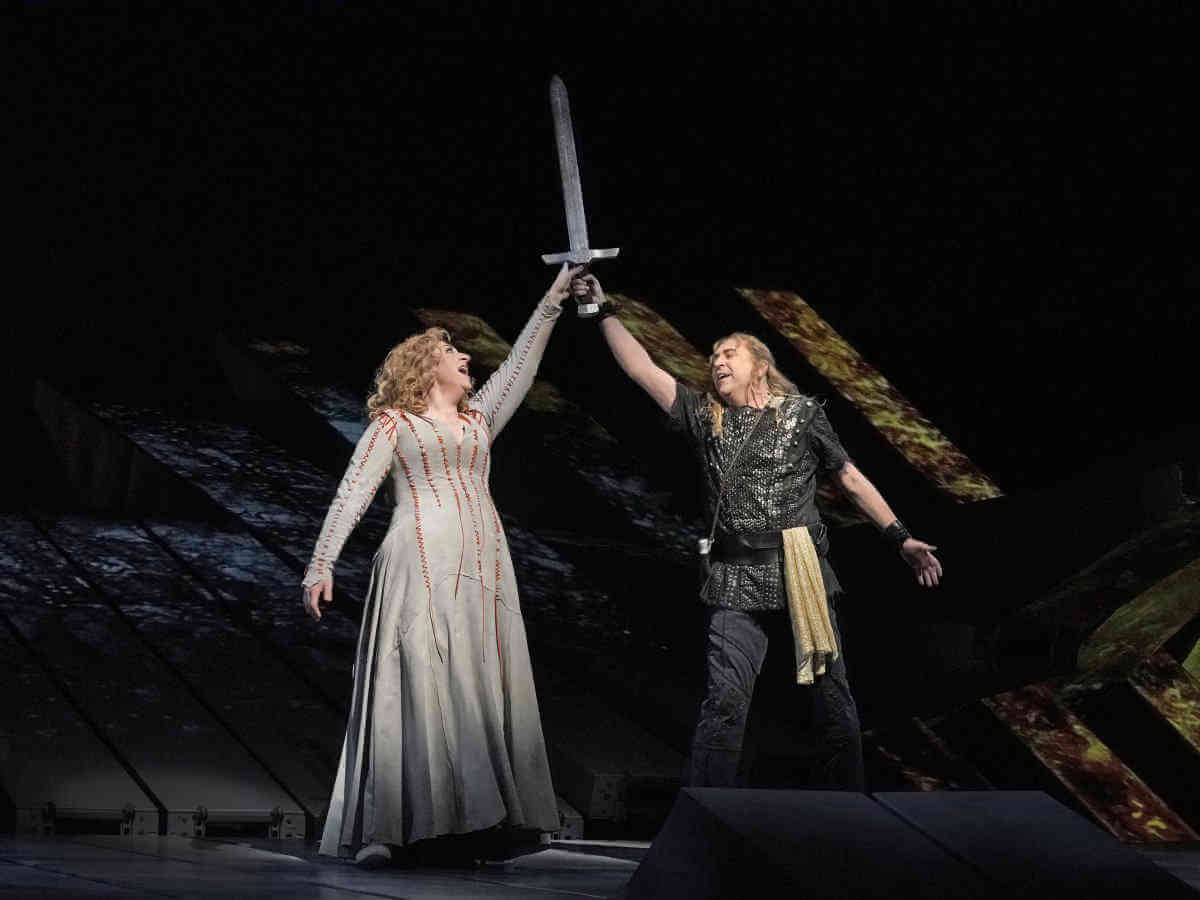

The cast was strong from top to bottom. There were several interesting debuts. Austrian tenor Andreas Schager made a confident, masterful debut as the more mature Siegfried. Like his alternate, Stefan Vinke, Schager has a high-placed true tenor sound, stage savvy, and impressive stamina. His voice is all bright metal, lacking the softer colors that Vinke summoned. In Act III, Schager’s Siegfried nailed the high C and triumphantly held on to it for several extra beats. A former operetta singer, he is a stage animal with abundant vocal and theatrical energy. Finding one viable, let alone excellent Siegfried has been an impossible challenge since Wagner’s “Ring” premiered. In the “golden age” of Wagner singing at the Met in the 1930s, there was only Lauritz Melchior. The Met miraculously found two superb Siegfrieds this season.

Less imposing but effective was the low-key villainy of Eric Owens as Hagen. Owens doesn’t possess the deepest, darkest bass out there yet Hagen’s lower range suits him better than Wotan’s does. It was interesting seeing a black man portray Hagen, who has an ingrained bitterness yet perverse pride in his outsider status. Evgeny Nikitin’s strong stage presence and imposing bass were somewhat wasted on Gunther — he needed more detailed direction to create a convincingly weak character.

Edith Haller, the other debutant, made the passive Gutrune an affirmative dramatic presence bringing an interesting mix of insecurity, seductiveness, and corruption to the character. Her mature soprano has womanly warmth but also some edge which also added character. Mezzo-soprano Michaela Schuster is another veteran German artist who brought biting textual detail and authority to Waltraute’s long narrative. Tomasz Konieczny scored again as a haunting ghostly Alberich in his one scene. Strong trios of Norns and Rhinemaidens compounded the uniformly strong ensemble casting.

Christine Goerke’s Brünnhilde provided a firm, constant focal point to the evening. Her tone is not as imposing as some earlier interpreters of the role — the volume is generous but not overpowering. Goerke’s soprano lacks the unbroken column of heroic tone of a Flagstad — consistently, Goerke must slim down the breadth of her dark soprano in order to surmount high tessitura. There have also been more profound interpreters of the Valkyrie turned mortal. Yet Goerke’s sound has warmth and femininity as well as dramatic power, and she has solutions for every vocal challenge thrown her way. I always felt that Goerke had a deep. honest connection to the character and sincerity in her delivery of text. Her large eyes and broad features create an excellent stage face that is expressive right up the highest balcony. Goerke’s open and positive offstage personality (so evident in her social media and public interactions) also illuminates her Brünnhilde, one character who chooses love over power or wealth. She remains honest and true to herself. It is Brünnhilde, not Wotan, who saves the world from the Ring’s curse. That positive energy and honesty provided a radiant hopeful center in Wagner’s dark universe. Goerke’s self-possessed heroine anchored the evening.

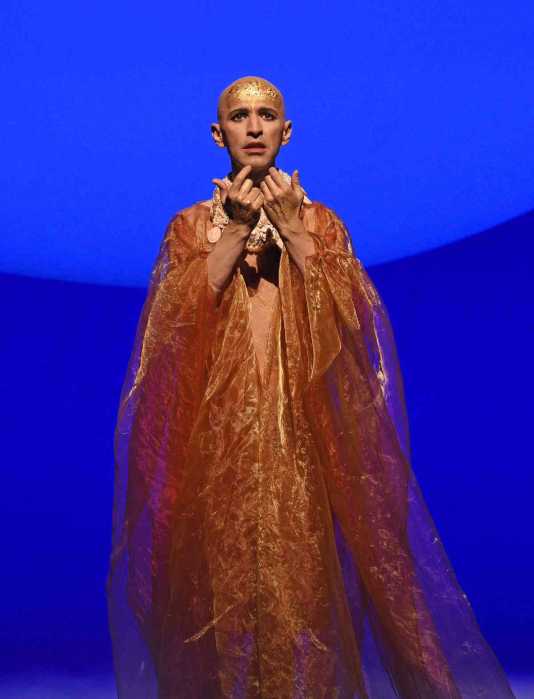

I will pass over the Lepage production as so much has already been said. This edition of Wagner’s “Ring” was about people taking center stage and not technology — it was the performers who provided abundant spectacle for the eye and ear.