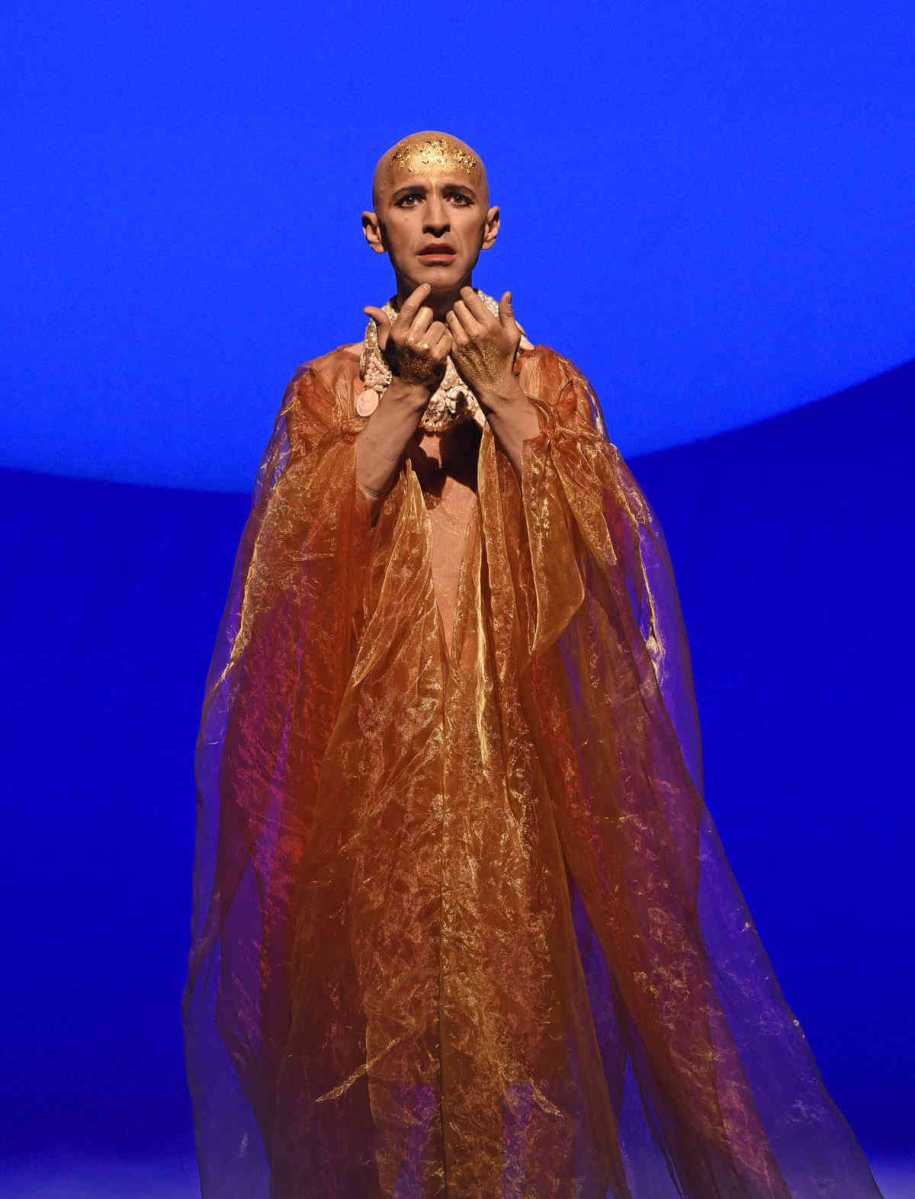

“Akhnaten,” first heard at Stuttgart in1984, has become the third Philip Glass opera presented by the Met. Seen November 12 in Phelim McDermott’s spectacular English National Opera staging centered around an amazing marathon star performance by Anthony Roth Costanzo, it was a terrific evening.

McDermott has varied and deepened the physically mesmerizing production since its 2016 English National Opera premiere. I’ve always enjoyed Glass operas more on second hearing. This time I appreciated the composer’s fascinating polytonal harmonics and heard intriguing echoes of baroque masters, particularly Bach and Pergolesi. The only scene I found frustrating — both the libretto and its realization by McDermott — is the very dated-seeming cameo of a contemporary archeologist describing the ruins of Akhnaten’s capital.

Costanzo’s brave performance has been discussed in some quarters largely in terms of the time he spends onstage nude. More important are the superb pinpoint physical, vocal, and emotional control he brings to the multiply mysterious pharaoh’s testing part. In her first Met role, mezzo J’Nai Bridges looked and sounded spectacular as Nefertiti; the beautifully staged duet between her and Costanzo and their characters’ vocal interplay (in life and posthumously) with the accomplished Icelandic soprano Dísella Lárusdóttir’s Queen Tye ravished the ear.

Also a carry-over from ENO, imposing bass Zachary James declaimed impressively as Amenhotep III. Aaron Blake’s secure, penetrating tenor aced the High Priest’s quasi-cantorial melismas and Will Liverman sang strongly as Horemhab. Conductor Karen Kamensek made a very welcome debut, though I found the playing initially somewhat muted; Acts II and III, though, blazed, and the chorus performed powerfully as well. “Akhnaten” appears through December 7; beg, borrow, or steal your way in, this production showed the Met at its best.

The Met’s “Turandot” October 26 proved most notable for Yannick Nezet-Seguin’s luxurious conducting, which mined the score’s osmotic modernism — underlining for example, dissonance when possible. Orchestra and Donald Palumbo’s chorus (much put upon in Franco Zeffirelli’s overblown staging) were in stellar form, guaranteeing a worthwhile evening. Act Two’s sensational mid-music set change still evokes understandable cheers, but otherwise the show looks tired (the ludicrous New Year’s dragon barely kept together), and its everything-but-the-kitchen-sink chinoiserie seems hopelessly offensive and puerile. Surely the Met, with its supposed emphasis on promoting dramatic values, can do better than this and mount a staging with a more psychologically and politically astute take on this highly problematic piece?

The casting was more than creditable but not ideal. I’ve heard Christine Goerke triumph in many parts, and she lends the role absolutely complete dramatic conviction in a way few “Turandot specialists” could even contemplate. But her top notes, though there, narrow in Puccini’s exposed peaks, and attacks were not always squarely on the note. When can we hear Goerke in something more interesting, like Ortrud (fabulous in Houston) or Alceste?

By operatic tenor standards, Riccardo Massi made a handsome Calaf, and his liquid tone and genuine Italian diction counted positively, though he should abjure the Riddle Scene’s high C in future. Gabriella Reyes earned buzz with her fine “Aida” Priestess last season; here she delivered a highly professional “cover” performance as Liu: the voice has the quality and vibrancy for Musetta potential, but on this occasion she didn’t offer sufficient dynamic shading for the self-sacrificing slave girl’s exquisite music. James Morris, at the Met since 1971, sounded recognizably himself as Timur if inevitably less steady and strong than in his World’s Reigning Wotan days. Besides Carlo Bosi’s superbly incisive Altoum there were strong contributions from sonorous baritones Alexey Lavrov (Ping) and Javier Arrey (Mandarin). Chorister Maria D’Amato, in the Handmaiden’s brief duties, sounded like another plausible Liu.

It was salutary to hear star countertenor Iestyn Davies — slated for Ottone opposite Joyce DiDonato in the Met’s “Agrippina” a few months off — in the intimate confines of Carnegie’s Weill Hall October 19. Working with the excellent five-member string ensemble Fretwork, who offered several finely articulated instrumental selections, Davies presented a keenly considered program spanning several centuries and languages. I wanted more light in the room to read the texts. Davies — working, as most recitalist seems to do now, with a music stand — proved most expressive in his native language: pieces by William Byrd (including a transfixing memorial piece to fellow composer Thomas Tallis), Henry Purcell’s exquisitely set “O solitude” and some archaizing pastoral songs by Ralph Vaughan Williams. A complex “Lamento” by Johann Christoph Bach (Johann Sebastian’s paternal cousin) proved astonishingly moving. Three Carlo Gesualdo songs emerged well-shaped but featured rather bloodless Italian declamation. Davies fared better projecting the texts of two slow Handel arias, a pre-slumber musing from “Orlando” and — oddly — that staple of non-baroque soprano’s recital numbers, Cleopatra’s “Piangero la sorte mia”. I might have preferred Sesto’s stop-time “Cara speme.” Davies’ instrument lacks a broad range of tone color, but throughout he savored tapered dynamics and used rhythmic accent expressively. This fine evening’s encore was — aptly — Purcell’s enchanting “Music for a while shall all your cares beguile.”

On November 1, Weill presented Golda Schultz’s highly satisfying New York debut recital. Known for Pamina and Nannetta at the Met, the highly musical, very appealing South African soprano offers Strauss’ Sophie there next month. Her readings of Schubert and Richard Strauss lieder proved unfussily straightforward, with the former’s “Suleika” songs a special highlight. Pianist Jonathan Ware brought greater specificity and accuracy to the programs wider-ranging second half: Amy Beach’s highly melodic “Three Browning Songs,” Ravel’s sensuous “Scheherazade,” and the modernism-tinged cantata John B. Carter wrought from four classic spirituals. Schulz totally inhabited the English-languages texts. The pair offered the aptly enthusiastic audience a pristine “Nacht und Traeume” — Schubert’s supreme test of legato — and a heartfelt, nostalgic song in Afrikaans, the soprano’s mother’s native language.

Andrew Ousley’s “Death of Classical Series” — a witty repost to media blowhard Norman Lebrecht that also presents dynamic events outside the box of traditional classical venues and programming — utilizes an atmospheric, otherwise inaccessible catacombs in Green-Wood Cemetery. This historic Brooklyn landmark, easily accessible via the R train when it’s behaving, offers spectacular landscaping and cinema-worthy vistas of Manhattan. October 8 brought Pergolesi’s influential 1736 “Stabat Mater”, which the brilliant composer penned weeks before dying at 26. What might he have achieved had he lived seven decades like Haydn or Gluck?

Molly Netter’s straight-toned soprano, with pinpoint attacks, made for good contrast with Kate Maroney’s earthier, furrier mezzo; in fact these good, style-conscious singers sounded most energized in Pergolesi’s seven duets. The sacred work was bookended, without intrusive applause, by Arvo Paert’s “Fratres” and Barber’s iconic “Adagio for Strings.” There was much to enjoy musically, but Eli Spindel’s String Orchestra of Brooklyn suffered from some muddy “opening night” violin ensemble. String tone is hard to maintain in such spooky acoustics.

David Shengold (shengold@yahoo.com) writes about opera for many venues.