When author Camryn Garrett first began writing the draft of her middle grade debut, “The Forgotten Summer of Seneca,” she thought, “this will be a fun piece of New York history.”

The novel, released earlier this year, is rooted in the real but often-overlooked story of Seneca Village, a 19th-century community of free Black landowners and poor white immigrants who lived in what is now Central Park, located along the park’s perimeter of the West 80s. The village was razed in the 1850s, its residents displaced by the city and developers, to make way for the park.

Back in 2018, when Garrett first started working on her book, she didn’t imagine it would land in today’s fraught cultural climate, where the teaching of Black history and queer representation are increasingly under attack.

“At the time, I thought I’d get to do school visits and introduce kids to a piece of history they may not know,” she said in a phone interview with Gay City News. “By the time the book came out, it was like — oh, okay, we’re in a completely different landscape. There’s fear and uncertainty about whether we’re even able to talk about the basic tenets of Black history.”

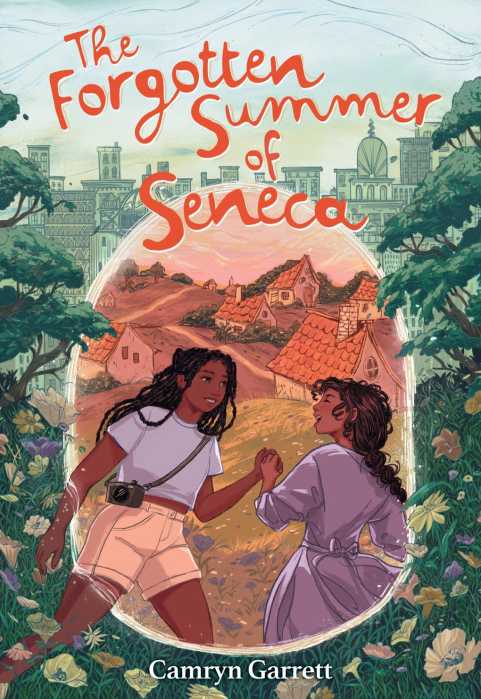

In “The Forgotten Summer of Seneca,” 12-year-old Rowan is spending the summer with her aunt Monica in Manhattan when she stumbles — literally — into the past. She trips in Central Park and falls through a time portal to Seneca Village, where Rowan finds herself navigating a magical, but fragile, community wary of outsiders, while grappling with her own grief over the recent loss of her late father.

The book blends history with fantasy, offering young readers both epic adventure and an education on a little-taught chapter of the city’s past. For Garrett, who’s a fan of “The Chronicles of Narnia” by C.S. Lewis, the element of magic was the breakthrough that unlocked the story after first attempting to write it as a young adult novel.

Garrett, a 25-year-old NAACP Image Award-nominated author who has four previously published novels, first learned about Seneca Village reading an opinion essay by Brent Staples in The New York Times.

“The village was described as a kind of Black utopia — a place where Black families belonged in the heart of New York City,” she explained. She had just moved to New York for college and was surprised she had never heard of the community. “I was really into New York history, and I thought, this is so cool — why don’t more people know about it?”

“I had tried writing middle grade before, and it didn’t work out,” Garrett said. “But this time, I was nerdy and obsessed with the history. I thought, this is exactly the kind of book I would’ve loved at 12. And once I tied in the grief element, it felt personal. That propelled me through the challenges.”

To ground her story in reality, Garrett worked with the online resources at the Central Park Conservancy, the non-profit that oversees the 843-acre park, which has an ongoing program series that will culminate in a community-informed plan to establish a permanent commemoration of Seneca Village in Central Park. For now, there are park signs, walking tours, and public events.

At a time when historical markers and plaques are being taken down or erased, Camryn pointed out, “You can go to Central Park, where Seneca once stood, and find multiple placards with information about where the church was, whose house was here.” Garrett, who admitted that it was hard to visualize the village at first, said, “Having those markers makes the history real.”

Seneca Village started in 1825, and the timing of her book’s release coinciding with the bicentenary was serendipitous. “I had no idea the anniversary was coming up,” Garrett said. “But when I visited, it felt almost spiritual to be there. To stand where villagers once stood — it affirmed the work I was doing.”

This past September the Central Park Conservancy partnered with the AME Zion Church in Harlem to celebrate “Founders Day,” the 200th anniversary of the first land purchase by church trustees and a congregant.

Writing fantasy presented Garrett with another challenge.

Though a pro at contemporary prose, fantasy writer friends urged her to create a detailed “magic system.” She resisted.

Instead, with her editor, she focused on the emotional arcs of the two female leads, Rowan and Lily. “Once we centered that, everything else clicked,” Garrett said.

The fantasy world-building is there, but it’s in service to the emotional magic between the characters.

Though this is Garrett’s first book for younger readers, she’s been a longtime fan of the middle grade genre. She cites authors like Renée Watson, Karina Yan Glaser (The Vanderbeekers series), and Rebecca Stead (“When You Reach Me”) as inspirations.

Garrett, who daylights as a bookseller, is aware of the current stakes for diverse children’s literature.

“Right now, queer authors are hurting, Black authors are hurting. Anyone who’s marginalized is having a hard time selling their books and promoting their books,” she noted.

As a bookseller, she uses her position to advocate for voices that might otherwise be unknown or overlooked. If someone comes in looking for a book recommendation, she recounted, “I’ll say, ‘Buy this book by this queer author.’ Or, ‘Buy this book by a Black author.’ And I’m really lucky when people are into that. I think it becomes sort of depressing when people … how do I articulate this? … When people might be like, ‘Hmm, let’s go for something more classic.’ Or, especially if they’re buying a book for their kid, they’ll say, ‘Well, this is what I read when I was little. So this is what I want.’ Which is fine, but frustrating. It’s hard when someone’s just, like, ‘I’m here to buy a book for a party.’ And I’m, like, ‘D’you know what’s going on in our country?’”

At the same time, she admitted that she didn’t want to go on school and library visits and just hit on the drumbeat of danger.

“Because kids, you want to engage them. And obviously that’s one way,” Garrett said. “But for me, I want them to find joy — in stories and storytelling and in this story.”