BY CHRISTOPHER BYRNE | What is the power of gender identity in our lives? That’s a provocative question given the fight for transgender rights, current debates about “gender fluidity,” and the fevered push for so-called religious freedom laws nationwide. These questions are at the center of Anna Ziegler’s new play “Boy,” now getting its world premiere at the Keen Company.

The plot, based on a true story, concerns what happens when a tragic accident during a circumcision of one of two infant twin boys results in destruction of his penis. The time is the 1960s, and the psychiatrist working with the child’s parents recommends that the child be raised as a girl. The doctor does not reveal the full motives behind his recommendation given his efforts at the time to carry out groundbreaking work on gender identity, but his concern for the child’s well-being and ability to function within society is genuine.

The central conflict of the play centers on how, as a girl, the boy never feels comfortable in his skin. When the truth is discovered, there follows inevitable emotional fallout from having lived outwardly with an imposed identity at odds with what the child inherently understands about himself. In the debate over “nature versus nurture,” playwright Ziegler comes down decidedly on the side of nature and is almost clinical in arguing that genitals alone do not determine gender.

Critical life choices power three new shows

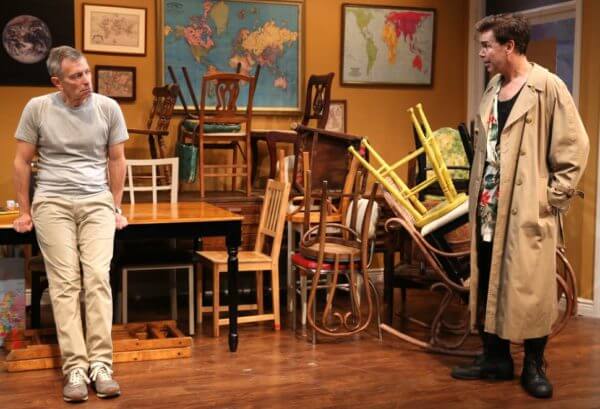

Making her case, however, poses critical challenges for this often problematic play. Ziegler struggles with the largely expository first part of the play, and the result is a clumsy collection of short scenes that include a letter, therapy sessions, and conversations that deliver information without revealing character. It feels mechanical and distant without a consistent voice. Only when the boy discovers the truth and begins to redefine himself as Adam, a name he chooses, does the play acquire any emotional heft.

Of course, we need the background information to understand Adam’s conflict and how he moves toward being an integrated, if damaged, male, but too many critical moments are reported rather than dramatized, blunting their impact. To be fair, Ziegler has set herself a tremendous challenge having an adult man play the character at all stages of his life, though that approach makes sense since the play is implicitly structured as a memory. Still, that choice comes at the expense of being able to feel Adam’s conflict until very late in the play.

The cast is consistently strong. Heidi Armbruster does a good job as Adam’s mother. Ted Köch is excellent as Adam’s father, and the scene where Adam confronts him is a glimpse of what this play might have been. Paul Niebanck is very good in the limited part of the doctor. Rebecca Rittenhouse negotiates the challenges of Jenny, Adam’s girlfriend, with nuance.

As Adam, Bobby Steggert once again demonstrates his amazing talent. He gives a subtle and deeply felt performance that fully encompasses the almost incomprehensible range of emotions Adam experiences as a girl and a boy. It would have helped the play to have the other characters as fully developed and employed less as documentary tools. Had Ziegler accomplished that, “Boy” would have lent richer insights into this critical and timely issue.

Once again, the Mint Theater Company has found a forgotten theatrical gem and given it a vibrant and fully entertaining production. In this case, the obscure object of delight is Hazel Ellis’ play “Women Without Men.” It concerns trauma, tempers, and treachery unfolding in the teacher’s lounge of a girls’ school in Ireland in 1937.

The title suggests that the presence of men would have prevented the pettiness and infighting we see among the teachers, but at the same time we come to understand that in 1930s Ireland unmarried women were second-class citizens who needed to fight for their simple survival. The play raises an interesting moral question: are kindness and forgiveness based on character or situation? The central conflict of the play is between Miss Connor, a longtime teacher, and new arrival Miss Wade. When Connor’s life work, a manuscript exploring “beautiful acts” through the ages,” is destroyed, she seeks to blame Wade for the crime. Exonerated, Wade doesn’t exact revenge… because she’s leaving to get married.

This well-structured play has idiosyncratic characters and paints a vivid picture of life in a socially constrained society. Under the direction of Jenn Thompson, the world of the school is rich and believable. The 11-member company is consistently excellent. Standouts include Kellie Overbey and Emily Walton as Miss Connor and Miss Wade, respectively, Mary Bacon as Miss Strong, who gives a lovely performance as a woman resigned to her lot yet struggling to keep her bitterness in check, and Dee Pelletier as the put-upon French teacher.

“Women Without Men” beautifully captured the myriad small eruptions that occur in an insular world where egos and perceived slights make up a big portion of daily life.

Sky Pony’s “The Wildness” now at Ars Nova is an imaginative immersive multi-media musical that is definitely out there in terms of production, but at its core is a simple story about children trying to make sense of the world. Told as a Jungian fairytale, the show has echoes of classic epics in which going into the unknown reveals knowledge that might have been better left obscure. What makes “The Wildness” so riveting is that it’s largely told from a child’s perspective, giving it a powerful innocence that is consistently compelling.

The story is punctuated by moments when the cast engage in “overshares” that underscore how the elemental fears of childhood carry through to affect our entire lives. The songs by Kyle Jarrow and the text by Jarrow and Laura Worsham are rock-inspired magic. Worsham plays Lauren as well as her fairytale alter-ego Zira, and her voice is simply spectacular. The rest of the cast, all of whom seem to be having a wonderful time, are equally good as well. Sam Buntrock directs with an outstanding balance between playfulness and emotional truth, and the entire experience, with the audience seated on hassocks around a runway, is breathtakingly original, exuberant, and heartfelt.

BOY | Keen Company at the Clurman Theatre, 410 W. 42nd St. | Through Apr. 9: Tue.-Thu. at 7 p.m.; Fri.-Sat. at 8 p.m.; Sat. at 2 p.m.; Sun. at 3 p.m. | $62.50 at telecharge. com or 212-239-6200 | One hr., 40 mins., no intermission

WOMEN WITHOUT MEN | The Mint Theater Company at New York City Center, 131 W. 55th St. | Through Mar. 26: Tue.-Sat. at 7:30 p.m.; Sat., Sun. at 2:30 p.m. | $27.50-$65.00 at nycitycenter.org or 212-581-1212 | Two hrs., 10 mins, with intermission

SKY PONY’S THE WILDNESS | Ars Nova, 511 W. 54th St. | Through Mar. 26: Mon.-Thu., Sat. at 8 p.m.; Fri. at 7 & 10 p.m. | $46-$66 at ovationtix.com or 866-811-4111 | Ninety mins., no intermission