“Memoir of a Snail,” by out gay writer/director Adam Elliot, is a poignant stop-motion animated feature. Grace Pudel (voiced by Sarah Snook) recounts her life to Sylvia (David Williams) after her eccentric friend Pinky (Jackie Weaver) dies. She describes her childhood with her twin brother Gilbert (Kodi Smit-McPhee) and how they were sent to separate foster homes after their father dies.

Grace falls in love with Ken (Tony Armstrong), and Gilbert starts to act on his same-sex attractions, but each encounter difficulties. Elliot’s film delivers some salient messages about freeing ourselves from the cages we create, and how to move forward in life even when the chips are down. The imagery is fabulous, and Elliot spikes his affecting film with some dark humor. (This animated film is not for young children).

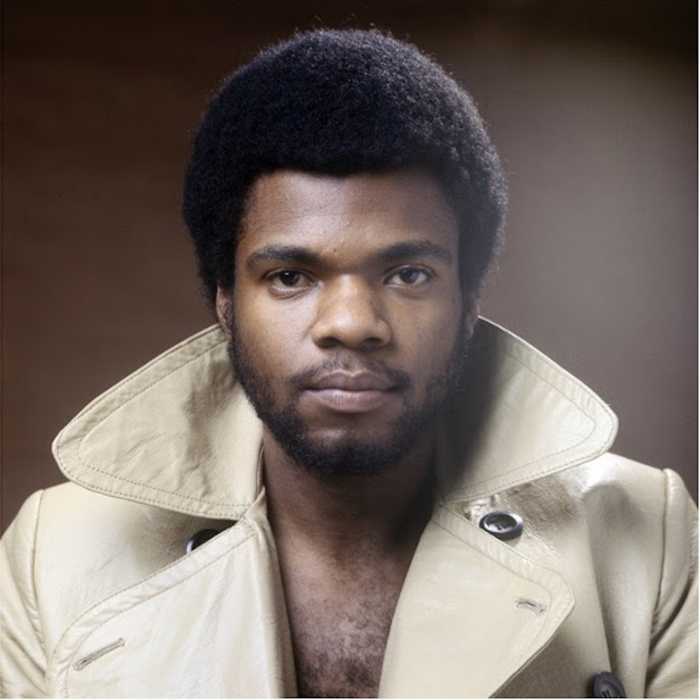

The Oscar winning director — his “Harvie Krumpet” won the Best Animated Short category in 2004 — spoke with Gay City News about making “Memoir of a Snail.”

You use stop-motion animation for “Memoir of a Snail” as well as all of your films. What is it about this painstaking process that appeals to you as a storyteller?

You need a certain temperament. It boils down to the fact that I just couldn’t sit in front of a computer screen all day. Even at film school, watching computer animation emerge, I didn’t want to do that. I like using my hands. I still do my storyboards on paper. It’s not that I’m a luddite. There is something primeval about using clay, that I really love; it satisfies all my desires and urges, and I think the people I employ are like-minded.

I admire the craft that goes into your film. How long did you work on the film?

Eight years. My accountant said to me once, “God, Adam, what you do must be tedious. And I said, “Well, you’re an accountant. How can you say that?” I think what’s tedious is the financing. It took us three years to raise the money. Then we had COVID. My animations are quite quick compared to other stop-motion films like “Pinocchio,” which took two years to shoot, whereas we shot this in 33 weeks. The post-production was slow. It took six months to edit the film, which took longer than we thought.

What inspired you to tell this particular story with its downs and ups, mainly from Grace’s point of view, rather than toggling back and forth between her and Gilbert?

I always say, if you’re not an emotional wreck by the end of one of my films, then I’ve failed. I wanted to do things little bit differently with this film. Up until now all my other films had a voiceover like an anonymous narrator. I wanted to tackle a memoir in a different way. Instead of Grace telling story to the Ether, I thought it would be nice if she was actually telling the story to a creature or animal or snail. That’s how it evolved. a snail is a better metaphor, because, you know, you touch a snail’s antennas, and they retract, and that’s what Grace is doing her whole life. She’s retracting into her shell and using that as a shield. Also, snails can only move forward. I love that sort of metaphor and analogy. The swirls on a snail shell provide a visual motif I love, and one that is sort of symbolic of life going full circle. So, there are lots of these lovely little connections that I thought were poetic and metaphorical.

When you’re talking to a creature, they can’t talk back. The snail is very ambiguous. Is she listening to Grace? Or is she just doing her job as a snail? Is she a sentient being? Is she really empathizing with Grace? And I sort of like leaving that a bit of a mystery.

There is also a prominent theme about letting go and escaping from things that try to control or contain us. Grace hoards snails, which provide her a sense of comfort, but she also realizes that she needs to dispose of them to move on with her life at one point. What observations do you have about our need to be soothed and face fear?

Extreme hoarding is all about dealing with trauma and suffering. It’s a coping mechanism. Hoarders give a lot of sentimental value to every single object — way more than it actually needs. I wanted her hoarding to be her comfort zone, to hide from the world and shield herself. We all have way more things than we need. Do you need it or want it?

If Grace collects snails, what do you collect and why?

My partner and I are reformed hoarders. We had a lot of bad taxidermy. I collected chests of drawers and getting old antiques. We filled a warehouse full of this stuff and then we downsized and got rid of it all. It was very cathartic. It really made us realize that what is important is not things but experiences. We live in a small apartment, and we don’t have a lot of stuff anymore. And it’s really quite liberating.

“Memoir of a Snail” is very much a fable about outsider characters becoming empowered. The characters are different, embracing their eccentricities. This will resonate with many queer viewers. As a gay filmmaker, is that deliberate?

All my films deal with the outsider or underdog — people who are perceived as different, marginalized, or misunderstood. That ties to the gay experience. I had a gay character in my last film, “Mary and Max,” but he was quite superficial. This time, I wanted to go deeper. I wanted Gilbert and Grace both to be empathetic and identifiable. A lot of people see Grace as being on the spectrum, and Gilbert is getting a lot of positive responses. We have had a few young people who found the gay conversion therapy sequence triggering, and they didn’t think it should have been in the film. And I argue if we don’t discuss these subjects in art and in storytelling and in cinema, where do they get discussed? But, of course, I don’t want people to be triggered in a negative sense or offended. But why can’t we tell these stories in animation?

“Memoir of a Snail” contains nudity, features swingers, and includes a disturbing fetish, as well as queer content. Can you discuss making animation for adults?

I’ve been getting this for 30 years, people coming up to me saying, “Oh, I don’t like animation, but I liked your film.” It just goes back to the problem that that animation is not a genre, it is a medium. There is a long history of adult animation in Eastern Europe. We’re all brought up with Disney and Warner Brothers, and it’s just the mindset. You shouldn’t be bringing your children to my films. Don’t blame me.

What I appreciate most about animation is how you can portray something in a new way to make a point effectively. In your film, I was really struck by the horrific conversion therapy episode in the film that you mentioned earlier.

Animation is a wonderful tool, because we have that tool of exaggeration. We can stretch the characters’ faces. We can be very succinct. We can pare back, remove all the clutter, and communicate. I think that’s a lot harder to do in live action. We get to play God in animation, and we have a lot of creative control, therefore, a lot of creative freedom. It’s really liberating. It is a real luxury to have our worlds look however we want them to look.

You won an Oscar 20 years ago for your short film, “Harvie Krumpet.” Now, “Memoir of a Snail” could be a contender in the Animated Feature category. What are your thoughts having won an Oscar as a filmmaker who works in animation, about the impact it has had on your career?

The Oscar was a wonderful thing that happened without us planning or aspiring to it. Awards are wonderful, but I see them being like a bottle of wine — it makes you feel good for a few hours, and then you’ve got to move on. We call the Oscar “the Golden Crowbar,” because it opens doors a little bit, and it gets people interested in your next project. And that’s what it’s all about. I am trying to get the next treatment up and running. But, yeah, even a nomination is good for us. And, you know, it would it be nice to have bookends.

“Memoir of a Snail” | Directed by Adam Elliot | Opening October 25 at the IFC Center | Distributed by IFC Films