BY ANDREW BERMAN | Forty years ago this past Sunday, on December 4, 1971, John Stanley Wojtowicz married Ernest Aron in Greenwich Village, in what Wojtowicz described as a Roman Catholic ceremony.

This event is noteworthy for having taken place nearly four decades before the legalization of gay marriage in New York State –– in fact, almost as many years before the debate over equal marriage rights became the ubiquitous feature of American life it is today.

But this particular Greenwich Village gay wedding is also worthy of historical note for having precipitated events that led to perhaps the most fabled botched bank robbery in New York City history, immortalized in one of the most acclaimed and iconic American films of the 1970s.

On August 22, 1972, Wojtowicz, Salvatore Naturile, and Robert Westenberg entered a bank on the corner of East Third Street and Avenue P in Gravesend, Brooklyn, with the intention of robbing it. From the beginning, however, very little went according to plan.

Westenberg fled the robbery before it even began when he saw a police car nearby. The bulk of the bank’s money had already been picked up by armored car and taken off-site, leaving a mere $29,000 on hand. As Wojtowicz and Naturile were about to leave, several police cars pulled up outside the bank, forcing them back inside. They ended up taking the seven bank employees hostage for 14 hours.

What made this attempted robbery so notable, however, was more than just bad planning and tough luck. An unlikely bond formed between the robbers and the bank teller hostages, Wojtowicz being a former teller himself. The robbers made a series of demands of the police and FBI that included everything from delivering pizza to the bank to providing a getaway jet at JFK to take them to points unknown.

What proved most unusual, though, was the fact that word leaked out that Wojtowicz was robbing the bank to pay for a sex-change operation for Aron, with whom he lived at 250 West Tenth Street in the Village –– then a single-room occupancy hotel since restored by designer Stephen Gambrel as a classic West Village townhouse. Aron –– who later, in fact, got the operation and lived out her life as Elizabeth Eden –– was even brought to the site of the hostage stand-off in an attempt to get the robbers to give up.

Throughout all of this, Wojtowicz became an unlikely media celebrity, an anti-hero who taunted the police with shouts of “Attica” –– referring to the 1971 upstate prison standoff in which dozens of prisoners and guards were killed in what was later determined to be an unnecessarily overzealous and brutal state trooper raid.

As a growing crowd gathered and TV cameras swarmed to the site, Wojtowicz also seemed to champion the plight of the bank tellers and fast food delivery workers with whom he interacted during that long August day.

Unsurprisingly, the robbery did not have a happy ending. En route to JFK, Naturile, who was only 19, was shot and killed by the FBI. Wojtowicz claims he made a plea deal that the court did not honor, and he was sentenced to 20 years in prison, of which he served 14.

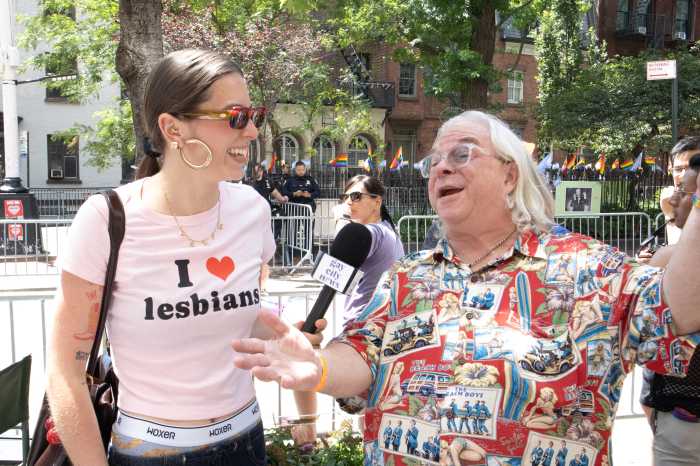

Given the intense interest in the robbery and the improbable cult-hero status Wojtowicz achieved, the story did not end there. Writing in Life magazine, Peter F. Kluge and Thomas Moore recounted the incident in an article titled “The Boys in the Bank” –– an allusion to the 1968 Mart Crowley play, “The Boys in the Band,” a landmark of gay theater. The Life story was the basis for a 1975 feature film, “Dog Day Afternoon,” directed by Sidney Lumet and written by Frank Pierson. Al Pacino, in what came to be one of his most celebrated roles, played Wojtowicz, and John Cazale played Naturile. Ironically, both had starred in “The Godfather,” which Wojtowicz had seen the morning of the robbery and upon which he based some of his plans. “Dog Day Afternoon” garnered six Academy Award nominations –– winning the screenwriting Oscar –– and remains one of the most critically acclaimed films of ‘70s cinema.

While the failed bank heist became the stuff of pop cultural legend, Wojtowicz himself did not prosper much from his enduring notoriety. He earned $7,500 for the sale of the rights to the story, and one percent of the profits from the film, that money used to fund Aron’s sex-change operation. Though he supposedly refused to speak to screenwriter Pierson who was seeking details for the script, Wojtowicz did not shy away from disputing several elements of the film. He agreed, however, that he and Naturile were accurately portrayed by Pacino and Cazale.

Coming during the nascent stage of the gay liberation movement, activists fiercely debated whether Wojtowicz’s actions on Aron’s behalf helped or hurt their cause. Wojtowicz had been an active member of the Gay Activists Alliance, a colorfully militant direct action group, and participated in their regular meetings at their former firehouse headquarters in SoHo.

Wojtowicz got out of jail in 1987. Sadly, Eden (formerly Aron) died shortly thereafter of AIDS. Wojtowicz was said to have been living on welfare in Brooklyn when he died of cancer in 2006.

Andrew Berman is the executive director of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, on whose blog at gvshp.org this article first appeared. Can you read the unpublished letters from John Wojtowicz to the New York Times, in which he describes his version of events and disputes what was presented on film. You can also read the late Village Voice writer Arthur Bell’s contemporaneous account of his phone conversations with his acquaintance Wojtowicz during the robbery. Bell describes the debate that followed the failed robbery at the Gay Activists Alliance Firehouse.