Dear Yoko Ono,

Years, years, and years ago, in 1980, a pathetically deranged man murdered the love of your life. You were walking home, into the Manhattan building where you lived, and suddenly this man, seeking the world’s adoration, gunned down your husband, John Lennon. Mark Chapman was given a 20-to-life sentence.

After almost four decades, he remains in prison. You want to keep him there for the rest of his life.

One year before John Lennon died, across the river in Brooklyn, a 21-year-old woman and her teenage friend broke into an apartment and killed the elderly couple who lived there, stabbing them 70 times when they refused to hand over money for drugs. Valerie Gaiter was given a 50-to-life sentence. She entered prison 40 years ago and died this August in the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility of untreated esophageal cancer, having been told for months that the pain in her throat was just acid reflux.

That’s what sending someone to prison for the rest of their life means. Aging into sickness and death in a place where the food is bad and healthcare barely exists. Because, gratifying as it may feel to see people sent off to rot behind walls, there are two unseen realities in play: (1) People who want someone to die in prison usually have no idea of what prison is like; and (2) Bad as prison can be, people inside can and do change.

Since 2000, when Chapman became eligible for parole, you, Yoko Ono, have written letters to the New York Parole Board asking that he be denied, saying Chapman’s release would “bring back the nightmare, the chaos and confusion”; that for the safety of your family, and his own safety, Chapman should remain locked up.

In later years, you’ve relied on your attorney to convey the message: “Lennon’s widow Yoko Ono has consistently opposed release.”

Out here in the world, we, who also miss John Lennon, take little notice. Like you, we’ve gone on to weather AIDS, 9/11, an exploding prison population, and so much more.

Back in 1979, Amber Grumet, the daughter of the couple Val Gaiter helped kill, couldn’t bring herself to attend her parents’ murder trial. She still has trouble holding herself together. Last year, she told City Limits that she didn’t know if she wanted Val Gaiter released. But Amber Grumet did think prison sentences seemed too long; that more emphasis should be placed on rehabilitation.

“I’m very torn between my own individual situation and my politics and philosophy,” she said. “I tried to bring myself together into one human being. I finally gave up. That’s the way I exist.”

That’s pretty much how we all exist, Yoko Ono.

Remember, when so many of us — activists, students, artists — were trying to keep the 1960s together? When we either were following Che and creating “Two, Three, Many Vietnams” or imploring the world to “Give Peace a Chance?”

To paraphrase another John Lennon song, whether or not we wanted full-on revolution, we all did want to change the world.

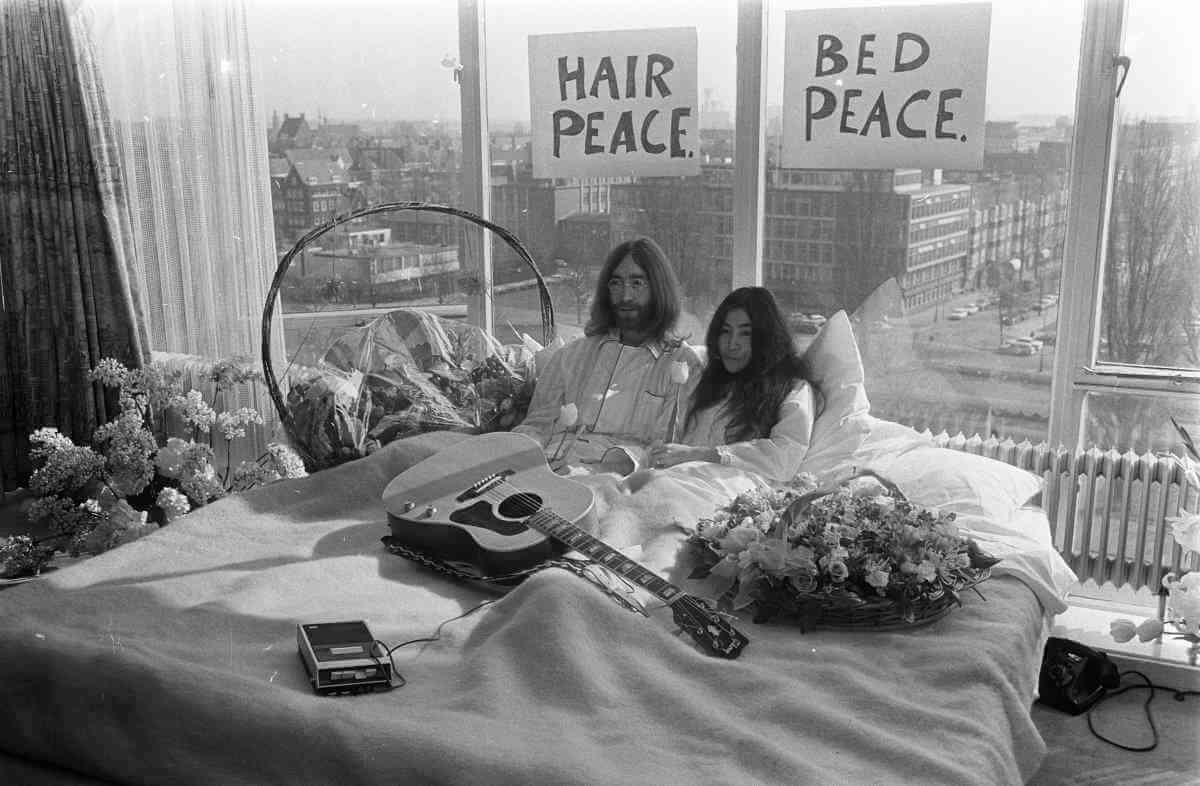

Remember those photos of peaceniks confronting stalwart American GIs with flowers? They seem unbearably quaint now. We smile wistfully at the memory of you and John in 1969, protesting the Vietnam War by spending a highly publicized week of your honeymoon in an Amsterdam bed, promoting “bed-ins for world peace.” The Peace Movement you endorsed welcomed home US soldiers, as long as they decried the war crimes this country had sent them to carry out. These were often men who killed or tortured hundreds of Vietnamese. No prison time for them.

Then Victory — the war ended! But, as the peace movement disbanded, new, stealthier wars commenced. Today, we can’t name all the countries where the US has sent its military; we can’t count the deaths for which this country is responsible.

Back in 1980, as the US government began sending aid to the Contras, Valerie Gaiter was beginning her prison sentence. When she died, 40 years and many proxy wars later, Gaiter still had 10 years to go before she would be eligible for parole.

At Bedford prison, everyone who knew Val Gaiter attested to how she had changed over decades. She worked training dogs for veterans with PTSD. She jumped at every opportunity for education or personal growth the prison could offer.

In 2012, despite 20 letters from the prison staff, Governor Andrew Cuomo denied her petition for clemency. A few months before she died, Val wrote in a letter, “The impact of what I did and the pain I have caused… will live with me for the rest of my life and forever be a reminder of what I was and how I can never be again… For that I am totally remorseful.”

Mark Chapman, with a clean prison record since 1994 and designated a “low risk” of recidivism, will probably go before the New York Parole Board again in 2020. He’s said he feels “more and more shame” every year for what he did; that he knows the pain he caused will linger “even after I die.”

My letter to you isn’t only about Mark Chapman. It isn’t only about the thousands of people aging in US prisons, who express profound remorse yet are too often refused by parole boards that won’t look beyond “the nature of the crime.” It isn’t even about the restorative justice projects now beginning to offer some hope. It’s a question I want to ask you, Yoko Ono.

What has Mark Chapman being in prison all these years done to heal your loss? Or ours, for that matter?

I would never dare ask you to forgive. Yet who is not worthy of being mourned? When and how should mourning determine Justice?

Your answer, Yoko Ono, will help us to see, if it was ever, ever, possible to Give Peace a Chance.