An obsession shared by young male athletes and debutante girls

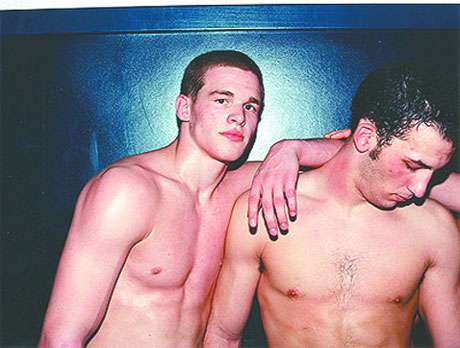

Collier Schorr’s current exhibition at 303 Gallery invites us to join a private high school wrestling team. The exhibit is the culmination of several years’ work in which Schorr, a lesbian, shadowed these young men, establishing an intimate and candid relationship immediately present itself in these photographs. This intimacy not only makes for sexy photographs, it also catalyzes a stark revelatory meditation on how people control their bodies to become something they desire.

To interpret these images merely as gender constructions is a mistake. Rather, they poignantly indicate the sometimes subtle, sometimes attractive, and at other times grotesque violence that accompanies the mechanisms we use to change our bodies. I think specifically of sports, gym routines, diets, diet pills, steroids, and cosmetic surgery.

The reference to the often hidden violence that goes into creating the bodies we desire is what distinguishes these photographs from the gamut of typical homoerotic imagery, placing them in the context of a broader, more pertinent discussion about the power of images. It separates them from last year’s Polaroid invitation to the Black Party, which featured a forlorn, if hot, young man with a shiner and a fat lip. No doubt, Shorr’s lesbianism empowers her to penetrate deeply to produce these gripping pictures of boys.

One photograph entitled “Beauty,” of an androgynous pre-adolescent boy with bright eyes, an innocent expression, and smooth porcelain skin, opens the show and functions as the “pretty” backdrop, or foil, to the exhibition, which actually displays older, less angelic-looking boys in the throes of vigorous exertions. These boys are the varsity “after” to “Beauty’s” pre-frosh “before.”

These muscled bodies—sometimes bruised and swollen—struggle, twist, languish on ropes, hang, pull, and recover. Their contorted faces capture the anguish, tension, and exhaustion of intense physical exertion.

Yep, it’s hot.

The ropes that hang from the top of the gymnasium—which also figure as subjects—loom ominously over and wind through these photographs. They are ever-present reminders of the inherent bondage of gender constructions, of the influence they wield over all kinds of human behavior.

In a recent interview Schorr indicated that she does photograph girls, only she uses boys to do them. Under Schorr’s scrutiny, a very specific “boy type”—the prep school wrestler— disintegrates into a readable fiction, a story we tell ourselves about boys. She exposes the whole system. How different, at the level of ritual, are these activities from those of, say, debutantes “training” for the ball?

In the same interview, Schorr recounted that when her older brothers wrestled in high school, “they were more obsessed with food than any of the girls I knew. There was a sense that they were trying to control their bodies in every way.”

These images ask us to consider the line between healthy athleticism or “improvement” and violence. Schorr digs into the sticky complexities of desire. In this regard, she is not that far away from another brilliant manipulator of desire, John Currin.

Strong religious overtones pervade the exhibition, broadening its scope. Many of the pieces reference Baroque religious paintings, specifically Caravaggio and Titian. The photograph titled “Lives of Performers (G.R.)” reminds me of one of my favorite paintings, Titian’s “Sisyphus,” in the Prado. Both capture young muscle- bound men caught in struggle, their bodies straining to achieve some elusive goal.

Schorr draws a parallel between religious and physical struggle, as if to ask why people struggle. What motivates us?

Casting useful light onto dark, obscure support beams, Schorr travels sensitively into the rough and tumble ways people create themselves. Her voyage into privileged space—wealthy, private, all male—is not unlike a journalist’s. If you let them, these photographs take you into a fantasy, flip it inside out, and bring you home. She makes you feel that even if you’ve never wrestled you are still playing on this team. I’d love to have one of them in my bedroom.