Lois Dodd’ s women, self-possessed, wear their nakedness matter-of-factly

When one thinks about it, it’s a little sad how seldom women are presented as casual creatures in the mass media. Their images are usually sexualized (just look at any magazine rack) or they must seduce the masculine camera in some proper, presentable way. Or worse, they are depicted bonding together in not very funny Hollywood scenarios.

These are several reasons why it’s refreshing to look at Lois Dodd’s paintings of female nudes. Here is a world that has no truck with the male gaze. Soft, blunt, occasionally bovine or ungainly, Dodd’s women wear their nakedness matter-of-factly. They have a dignity that Dodd presents as the true quality of the modernist nude.

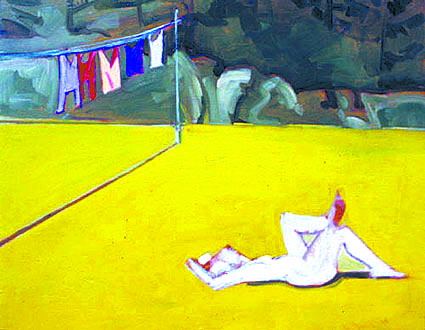

In their habitation of a timeless summer afternoon, Dodd’s women sometimes pose en plein air for other women painters. In several works, such as “Legs Up Against Tree” (2002) or “Figure in Hammock” (2000), they insinuate their shadow-tattooed bodies into the surrounding foliage. Or they approximate backyard sculptures as in “Three Nudes on Woodpile” (1999) or “Nude on Woodpile” (1999). They are always self-possessed. In “Tennis Anyone?” (1999, a little masterpiece that seems to nod toward Milton Avery, a nude woman lies on the grass, as unconscious and abstracted as the colorful laundry on the clothesline behind her.

Lois Dodd has a long history as a painter. She is 75 years old and works in New York City, rural New Jersey, and Maine. Along with her larger paintings, she does many on-the-spot smaller works. Dodd is partial to the vignette but her works owe nothing to photography. In her various unpeopled small landscapes that make up her uptown show, Dodd demonstrates precisely how a deftly placed piece of paint functions in a picture.

Dodd is a concise observer who is at pains to balance her motif with the factuality of the mark and her materials. In other words, she wants to make paintings that look like an ordinary person painted them with typical art materials. This is, of course, a political statement—a friendly, democratic one. Behind these benign surfaces lies the scope and skill of a Mandarin poet.