Revival of Wallace Shawn’s Reagan-era play probes inner fascism

Aunt Dan to Mother: “Don’t you understand that you and I are only able to be nice because our governments—our governments are not nice?… These other people use force, so we can sit here in this garden and be incredibly nice.”

In these days, when commanders in the U.S. armed forces justify their tactics in Iraq by telling The New York Times, “You have to understand the Arab mind. The only thing they understand is force,” there is probably no more appropriate play to revive than Wallace Shawn’s 1985 “Aunt Dan and Lemon. ” The play is running now in a wonderfully acted production at Theatre Row.

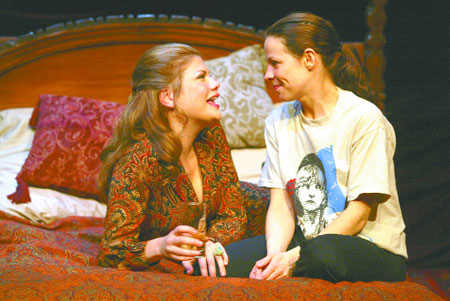

Shawn’s play challenges us to face our complicity in our government’s aggressions. Narrated by Lemon (Lili Taylor), a Londoner, as a remembrance of her latently lesbian childhood relationship with her parents’ glamorous friend, Aunt Dan (Kristen Johnston), the play jars our comfort philosophically and in its style of presentation. Its lengthy monologues, its flashbacks that run afield from the plot, and the way it breaks the fourth wall prevent us from cozying up as we might with more traditional dramatic form.

Aunt Dan, “one of the youngest Americans to ever teach at Oxford,” is obsessed with Henry Kissinger. She defends his murderous policies in Vietnam in lusty, comically shocking speeches. Under Aunt Dan’s lingering influence, the grown Lemon, a reclusive with an eating disorder, spends her days reading about, and developing sympathies toward, the Nazis. The main characters are iconoclasts, but they are far from unintelligent, or unintelligible.

Their arguments are so logically––and in the case of Lili Taylor’s eerily poised Lemon, so coolly and politely––presented that they raise the specter of the fascist in all of us: "Now today, of course, everybody says, ‘How awful! How awful!’ And they were certainly ruthless and thorough in what they did. But the mere fact of killing human beings in order to create a certain way of life is not something that exactly distinguishes the Nazis from everybody else . . . Our human nature is derived from the nature of different animals, and of course there’s a part of animal nature that likes to kill. If killing were totally repugnant to animals, they couldn’t survive. So an enjoyment of killing is somewhere inside us, somewhere in our nature."

The New Group, under the direction of Scott Elliott, has revived Shawn’s controversial Reagan-era hit in attempts to, as Shawn himself has said, “hold a mirror up to nature” and critique its banal brutality. As anti-war theater, the production has received much-deserved raves. But there’s more to our “nature” than geopolitics, and the play’s commentary is more layered than most critics have allowed.

Among the most disturbing and resonant elements of the play are its treatment of gender and sexuality. Putting fascistic philosophies in the mouths of females, Shawn uses gender to disenfranchise the audience of its easy notions of aggressive masculinity versus pacifist femininity. We can’t write these women off as testosterone-poisoned machos. The only real action onstage is a woman’s murder-for-hire of a man. In this sense, Shawn moves beyond gender to a universal critique of humanity.

Dan, short for Danielle, is a man’s name, and Aunt Dan, as originally played by the androgynous Linda Hunt in the role Shawn wrote for her, was an intellectualized s/he, an Orlando first encountered by Lemon’s Mother (Melissa Errico) wearing “delicate white Victorian blouses and these rough 19th century men’s caps.” Lemon is equally neutered by her nickname, by an illness that stunts her female form, and by childhood recollections which keep her adulthood at bay.

But, particularly in the casting of Kristen Johnston as Dan, The New Group’s production accentuates more traditional dynamics of gender and sexuality than the original run did. Vibrant, vampy Johnston is a full-figured Amazon, oozing a hearty, feminine libido turned on by power. Her lovers are all like Geoffrey, “this gigantic prince, the most famous professor in the whole university, a great philosopher.” Even when she hooks up with a woman, the prostitute/murderess Mindy (Brooke Sunny Moriber), it’s in response to Mindy’s subversive embodiment of power when she recounts the murder of the police informant Raimondo (Carlos Leon).

“My teeth were chattering as I listened to the words of this naked goddess… I was incredibly in love,” Dan tells Lemon.

But Mindy’s story illustrates a gendered truism of the play: under capitalism, power is money, and money is still controlled by men. Freddie, a man who can afford to keep his hands clean, has paid Mindy to murder. As Mindy’s male friend/lover Andy (Isaach De Bankolé) tells it, “I really enjoyed giving money to Mindy, because she didn’t have it, and she really wanted it, and she loved to get it,” though she “still ended up at times without a penny in her purse.”

Aunt Dan’s desire for Mindy quickly fizzles against the reality of Mindy’s impotence, while her obsession with Henry Kissinger, the fetishized, all-powerful “father figure,” persists and is projected onto Lemon who, though she admits to a mutual, chaste desire to kiss Aunt Dan, expresses her sexuality most strongly in her admission that she “was quite prepared to serve Kissinger as his personal slave.”

“I imagined he liked young girls as slaves,” Lemon says. “Well, he could have his pleasure with me, I’d decided long ago, if the occasion ever arose… It wasn’t how I planned to live as a general rule, but for Kissinger, I thought, I would make an exception. He served humanity. I would serve him.”

As for her love for Aunt Dan, Lemon discards the older woman as soon as a fatal illness renders her all too human. Visiting Dan in her London flat, Lemon says, “In the bathroom there are a thousand things I don’t want to see—what pills she takes, what drops, what medicines… I feel no need now ever to see her again.”

The Nazis are ultimately more satisfying to Lemon because “they managed to accomplish a great deal of what they wanted to do.” As she describes them, men named “Heinz” and “Rolf” “were trying to create, or re-create” a “sort of society of brothers” by exterminating Jewish “women and children… in Treblinka” and other camps. In Lemon’s mind, the Nazis were rational, powerful, and male.

Wallace Shawn in 1985 told The Times’ Michael Billington, “People like myself have been reduced to a gaping, open-mouthed silence in this particular period; and the response to Reagan by those who oppose him hasn’t been as inspired as one might hope… I’m trying to provoke a response in the many hundreds who I hope will see the play.”

The playwright might as well have been describing our contemporary situation, with the depressing dissipation of today’s anti-war movement and the relative muting of the left. Ultimately, The New Group’s revival of Shawn’s masterful play makes me yearn for contemporary geopolitical examinations—in effect, for more theater like “Omnium Gatherum.” For that, we might have to wait for The New Group’s next production, the world premiere of Palestinian-American playwright Betty Shamieh’s “Roar.” Until then, by all means, go see “Aunt Dan and Lemon” and get a good dose of self-examination. Just remember that the image in the mirror is fully possessed of, not only a political agency, but a gender and a sexuality as well.