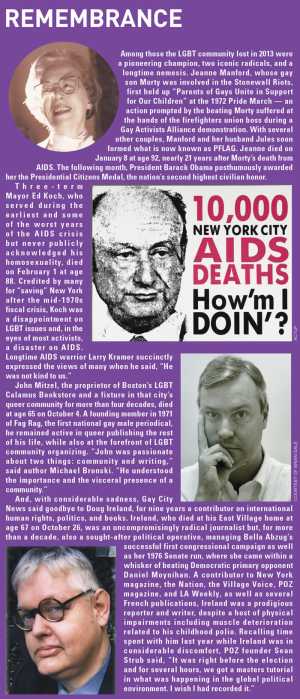

Morty Manford with his mother, Jeanne, in the 1972 Christopher Street Liberation Day march. | P-FLAG

When I opened up the New York Times last week and read David Dunlap’s obituary for Jeanne Manford, who died at the age of 92, I recalled that she was the founder of P-FLAG, but most importantly that she was Morty Manford’s mother. I remember Morty so well. Who wouldn’t? It was hard to forget him.

The piece in the Times was glowing and wonderful — Jeanne was a miraculous presence in those early days of what is now called the LGBT movement — but it didn’t mention that Morty was at one point president of the Gay Activists Alliance, one of the two original radical political organizations founded in New York directly after the June 1969 Stonewall Rebellion. The first was the Gay Liberation Front, of which I was a member, and from it, a few months later, sprung GAA, the less radical, more mainstreamed group of the two.

I ran into Morty a lot, talked with him, socialized with him, danced near him at the outrageous Saturday night dances at the GAA Firehouse on Wooster Street, but always encountered him slightly from a distance. Unlike others in the GAA I was closer to — Arthur Bell, Arthur Evans, Marc Ruben, Pete Fisher, and Bruce Voeller, all of them now dead — Morty always seemed more set off by himself. He was tall, thin, clean-shaven (unusual for those days of mustachioed guys), and quiet. Bell, a more lively presence whom you would immediately feel when he was near you and always one to coin a term, called him “Refrigerated Morty.” But the truth was Morty had the density and quiet of someone bearing stone-cut courage.

Jeanne Manford’s death awakens memories of the special gifts her son Morty gave us all

He had come out while still living in his Jewish family home in Queens at the age of about 16. In 1968, pre-Stonewall, he joined a handful of other young gay activists to form Gay People at Columbia University, an event that made the front page of the New York Times. He was smart and younger than I was by several years, which would have made him barely bar-age by the time of Stonewall. But he’d already internalized the most important notion of what liberation is — if you don’t stand up for yourself, no one else will. But if you do, others will join you.

Sometimes you may have to grab them, or shame them — but they will.

I’m sure this came from Morty’s own brand of secularized, New York Judaism, which at its core contains a very important spiritual and political message — authenticity and truth are everything, and you must fight for them. I had met lots of Jews in New York when, as a Southerner, I first came to the city, and they all felt the same way. Their attitudes had given birth to New York’s liberal Jewish tradition, something not as strong today as it was then. It was from families of this tradition that many found their way into the Gay Liberation Front and then into GAA.

I remember Morty speaking at meetings and rallies, and recall meeting his parents many times. They always seemed like complete riddles to me and most of my friends in the movement — none of us could imagine our parents doing what Morty’s did: marching with him, being out there openly with him. His mother was a dynamic schoolteacher from Queens; his father a tall, quiet dentist who reminded me of the actor Ralph Bellamy.

In 1972, after Morty was beaten up by Michael Maye, the president of the New York City Uniformed Firefighters Association — who was roughly twice Morty’s size and age — outside a Hilton Hotel ballroom where GAA pulled a zap to bring attention to the lack of press coverage on gay issues, Jeanne wrote a letter to the New York Post, then a liberal “family” newspaper, talking about what had happened to her gay son. She made no bones that she had one. When brought to trial, Maye, in a then-commonplace show of bigotry, was acquitted by a judge of any wrongdoing.

But publicity from the case again brought to light violence against gays, as well as the fact that Morty had a family standing behind him. You’d see Jeanne, her husband Jules, and Morty together openly at gay demonstrations and events. Soon enough, many other people in the same boat, of having a gay or lesbian child or children, joined them — and Jeanne became the founder of the first large “straight ally” organization in the world.

Before I learned of Jeanne’s death, I hadn’t thought about Morty in a long time. Like a lot of the GAA guys, he liked to wear leather, and I remember him in jeans, a dark GAA T-shirt, and a leather jacket while we demonstrated for gay rights or against the Viet Nam War. Back in this explosive “liberation” period of the gay and lesbian movement, there were what I called “fissionable” moments happening all the time. We had been people no one would talk about, and now the reality of who we were — people violent-prone goons like Michael Maye would try to kill if they could — was right there out on the streets, in meetings, and in newspapers, with real faces and real people attached.

And some of our parents along, as well.

I felt at that point that our movement had a “genius” to it — an animating spirit unafraid to look at the truth and create something important from it. At a demonstration I asked Arthur Bell, “Do you think our movement has a genius to it?” And he said, “Look around you. What do you think? Of course!”

Morty died on May 14, 1992, at his home in Queens, of complications from AIDS. His father Jules had died ten years earlier, and Morty’s only brother, Charles, died in 1966 — what an awful lot of deaths for Jeanne to take. I remember hearing about his death and taking it hard — that this young, beautiful guy who’d become a lawyer, had died. I’m sure that I still miss his quiet presence, but now it has been joined by Jeanne’s.

The latest book by Perry Brass, author of “The Manly Art of Seduction,” is “King of Angels, A Novel About the Genesis of Identity and Belief,” set in Savannah, Georgia, in 1963, the year JFK was assassinated. For more information about him, visit perrybrass.com.