Amidst an escalating national political firestorm about the status of transgender people in American society, the Supreme Court of the United States on Dec. 4 heard oral arguments in United States v. Skrmetti. In an epic series of verbal exchanges lasting nearly two-and-a-half hours, eight of the justices and the three advocates at the podium got into the weeds about the specific lawsuit challenging Tennessee’s ban on gender-affirming care for minors, but also, with an unspoken eye to what is almost certainly coming after Jan. 20, explored more broadly how persuasively any state actor needs to justify discrimination classifying on the basis of transgender status and whether drawing lines on that status inevitably must be characterized as sex discrimination.

Elizabeth Prelogar, the legal eagle superstar Solicitor General of the United States now with a mere matter of weeks left remaining in that role, and Chase Strangio, co-director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s LGBTQ & HIV Project, repeatedly and emphatically pressed the justices to simply remand the case back to the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, with instructions to apply a heightened standard of review demanded when policy lines are drawn based on sex classifications. Strangio also made history as the first transgender attorney to argue before the nation’s highest court.

Arguing in support of the ban on certain medical interventions for transgender minors, for only about a quarter of the total combined time of Prelogar and Strangio, was Tennessee’s Solicitor General, J. Matthew Rice.

Tennessee’s law, most frequently referred to as SB1, prohibits doctors from providing gender-affirming puberty blockers or hormones to transgender youth, but permits the same treatments for cisgender minors whose gender identity matches their sex assigned at birth. Tennessee’s law is one of two dozen nationwide that comprehensively ban gender-affirming care for transgender youth. Two additional states have bans on surgical treatments alone. Most of the bans have been challenged in either federal or state courts, but the challenge to the Tennessee law, involving three transgender minors, their parents, and a doctor serving as plaintiffs, reached the US Supreme Court first.

The court technically only granted review of this case on the petition from the Biden Administration (later allowing Strangio to also argue, though, because of a motion for divided argument from Prelogar), an intervening party below after it was first filed by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), a procedural point not mentioned at all during the Dec. 4 hearing, but one that ominously looms because the incoming Trump Administration will undoubtedly declare a switch in litigation positions when it assumes control of the Department of Justice in January. That will be well before a decision from the court, in a case this significant, is likely to be anywhere near ready for release.

Chief Justice John Roberts and Associate Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Brett Kavanaugh gave little indication in the tone and tenor of their questions that they are likely to come down on the side of transgender youth here, with several of them in one way or another expressing dismay about placing the court in the middle of what they characterized as a turbulent dispute amongst medical experts both domestically and abroad.

At the same time, liberal Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Ketanji Brown Jackson all made it pretty abundantly clear they are leaning the opposite way, with Sotomayor reminding Rice “when you’re 1% of the population or less, very hard to see how the democratic process is going to protect you” and Kagan declaring that “[t]he whole thing is imbued with sex.” Jackson found herself exasperated that her conservative colleagues were “undermining the foundations of some of our bedrock equal protection cases,” especially Loving v. Virginia, where the court said discriminating equally against all races was unacceptable. Rice was a kind of broken record when answering their questions, saying again and again that SB1 operates based on the medical purpose of these treatments, not on sex.

The late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg tragically passed away in September 2020, but one glimmer of hope on Dec. 4 was even the most conservative justices seemed to take for granted that her doctrinal legacy, her project of infusing the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment of the United States Constitution with protection against sex discrimination, at least for now, remains as constitutional infrastructure that they still need to seriously grapple with — but only if a case falls within its sphere of influence, and that, of course, remains the key question in Skrmetti.

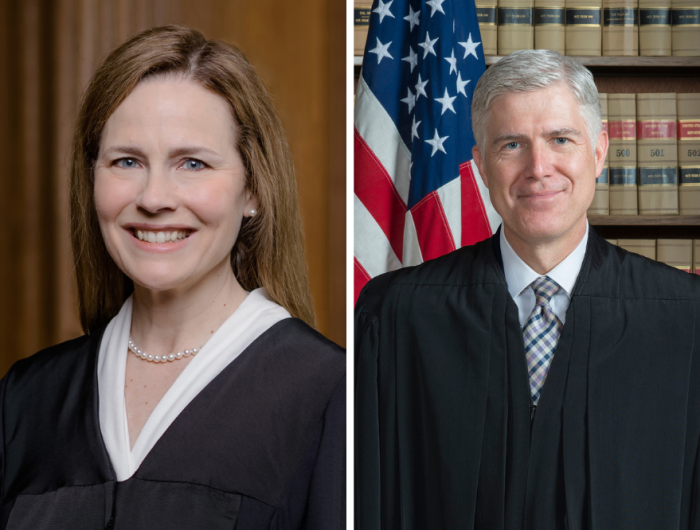

Meanwhile, another justice still on the court made waves for the deafening silence emanating from him. Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote the landmark Bostock v. Clayton County majority opinion in 2020, and that majority notably included Chief Justice Roberts. While that was a case involving statutory interpretation, its underlying logic — that discrimination against transgender people is undeniably sex discrimination — will be very hard to conceptually distinguish here in this constitutional context. With that in mind, his silence might have left him more room to eventually join the three liberal Justices.

If that is true, and that is an enormous “if,” the question of who could provide an all-important fifth vote for the plaintiffs, based purely on the questions she asked, looked most likely to come from Justice Amy Coney Barrett. She appeared to be genuinely wrestling with whether transgender people should be recognized as a suspect class, although Rice dismissively, but correctly, reminded her the court has not recognized a new suspect class in decades. Strangio, though, pointed her to the examples of cross-dressing laws and President Donald Trump’s ban on transgender people serving in the military as examples of a history of de jure discrimination, one of the key factors in the suspect class analysis and a point she repeatedly pressed both him and Prelogar on.

Justice Kagan sits to Justice Alito’s left on the bench, both physically and ideologically, and she turned to him whenever he was talking. However this case goes, her facial expression at those moments spoke volumes, indicating a gloomy combination of frustration and even sadness. Her remaining time on the Supreme Court bench will be spent watching a bloc led by Alito, or more likely a much younger replacement in the near future, in the constitutional driver’s seat to decide the full array of significant issues that come before the Court in the coming years and decades.

If the court keeps the case after the Trump Administration assumes power, a decision must be released by the court by the end of June 2025.