ACLU protects gay public school students in Kentucky, lesbian foster mom in Missouri

BY ARTHUR S. LEONARD

Courts in Kentucky and Missouri issued important gay rights ruling on February 17 in cases brought by the American Civil Liberties Union—upholding the right of gay people to be foster parents in Missouri and rejecting a challenge by conservative parents to a gay-inclusive diversity curriculum in Boyd County, Kentucky.

The Kentucky case grew out of previous litigation the ACLU had brought to vindicate the right of students at Boyd County High School to have a Gay-Straight Alliance (GSA) in their school. As part of the settlement after a preliminary court victory in that case, the school district agreed to provide gay-inclusive diversity training for school staff and students to address the anti-gay hostility prevalent at the school.

Diversity training was provided for staff before the 2004-2005 school year began, but the introduction of such training for students proved controversial, as parents of several students claimed religious objections and demanded that their children be allowed to avoid the sessions. When the students in question failed to appear for the training sessions after their parents had submitted written “opt out” demands to the school, the students received unexcused absences and their parents filed suit, claiming that their constitutional rights had been violated.

The ACLU, representing the gay students, moved to intervene in the lawsuit, and U.S. District Judge David Bunning, who had issued the original decision upholding the right of the students to form their GSA, granted the motion. Bunning then played the role of a mediator, helping all the parties to negotiate changes in the diversity curriculum to make it more palatable to at least some of the objecting parents, who had claimed that it orginally had been designed to promote homosexuality.

Ultimately the parties agreed on changes for the 2005-2006 school year that were aimed at promoting respect for differences using neutral language, but the parents still insisted that they should have a right to have their children opt out of the program. Bunning asked all parties to submit motions for summary judgment so he could rule on the legal claims.

Bunning’s opinion totally rejects the position taken by the protesting parents, pointing to numerous precedents that hold that protesting parents do not have a constitutional right to dictate the content of public school curriculum or to opt their children out of classes that are part of the curriculum. Although parents are free to send their children to private schools or to undertake home schooling, if they send their children to the public schools, they have to accept the curricular choices made by school administrators, so long as the schools do not cross the line into religious or anti-religious proselytizing.

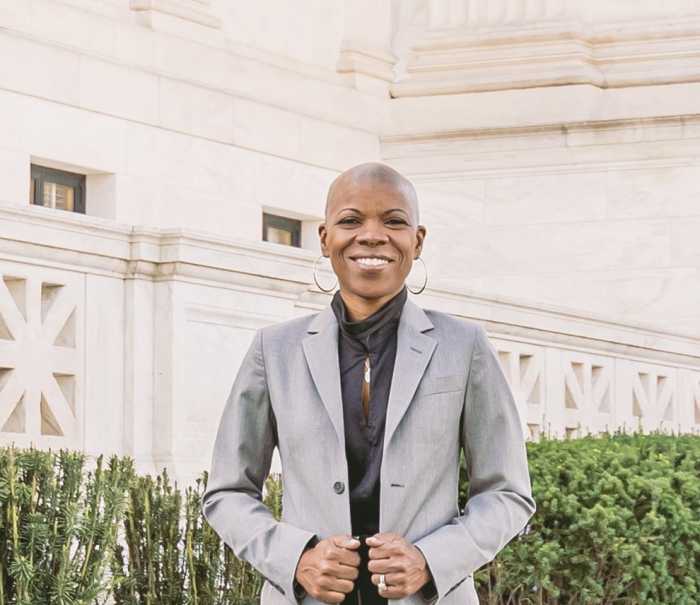

The Missouri decision reflects a situation that seriously questions the competence of child welfare officials in that state. The state’s Department of Social Services rejected an application from Lisa Johnston, a lesbian, to be certified as a qualified foster parent. The DSS found that she was superbly qualified, not least because she is a trained professional in child development issues and employed in a variety of programs involving counseling and teaching children. Because she is living with a same-sex partner, who is similarly qualified, the DSS decided that she “was not a person of reputable character.” That determination was based on her engaging in conduct made criminal by Missouri’s sodomy law. The failure of the Legislature to repeal the sodomy law after the Supreme Court’s 2003 decision in Lawrence v. Texas evidently led the DSS to conclude that the statute remained a valid basis on which to disqualify gay people from being foster parents, even though the state’s child welfare laws do not explicitly bar gay people from playing such roles.

Rejecting the DSS’s position, Missouri Circuit Judge Sandra C. Midkiff found that the sodomy law is not longer enforceable, and that to deny a superbly qualified individual the right to be a foster parent because she engages in conduct protected by the Due Process Clause of the U.S. Constitution was totally invalid. She also found that the evidence presented by DSS in the hearing in the case was not competent and was based entirely on unsubstantiated opinions, having nothing to do with the welfare of children.

“No moral conclusions may be drawn from a constitutionally unenforceable statute,” she wrote, finding that “there is no competent and substantial evidence upon the whole record that would support the Director’s conclusion that Petitioner lacks ‘reputable character.’ Viewing the record as a whole, there is only evidence that would support the excellent character and professional reputation of the Petitioner.”

gaycitynews.com