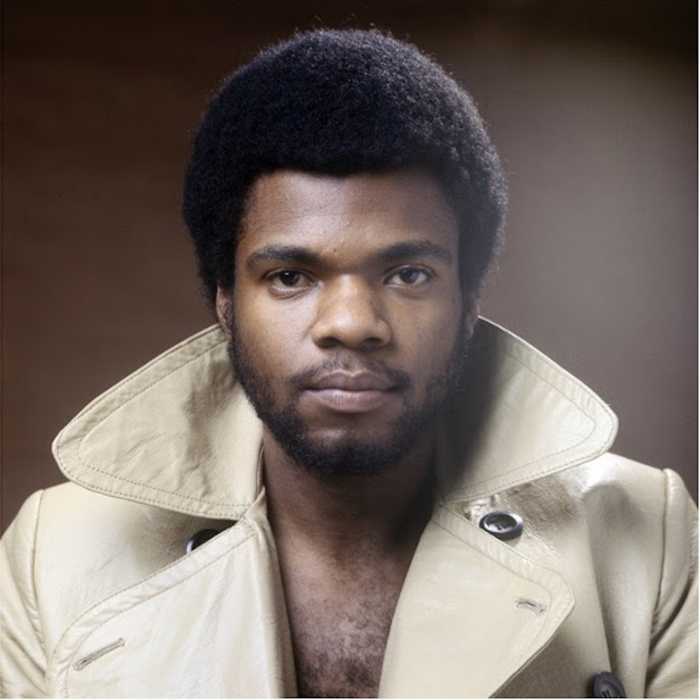

Alana McLaughlin, the second openly trans MMA fighter (after Fallon Fox), is the subject of the inspiring new documentary, “Unfightable.” Director Marc J. Perez recounts McLaughlin’s efforts to train and fight in a 2021 Combate Global undercard.

She gets the opportunity when MMA founder and promoter Campbell McLaren offers her a fight against Celine Provost. However, finding an opponent and a gym for McLaughlin to train in proves difficult. Moreover, there is backlash from members of the MMA community who post negative comments on social media about a trans MMA fighter.

Perez captures the ingratiating McLaughlin as she trains — mentally and physically — for her MMA debut, while also addressing her life pre-transition including her time as a soldier in the U.S. Army Special Forces.

The athlete/activist spoke with Gay City News about making “Unfightable.”

What made you decide to make this documentary and tell your story as you were training?

It felt like it could be important with the moment of time that we’re in. Fallon Fox did this same stuff 10 years ago. She was the first openly trans woman in MMA, and it generated outrage. Fighting in MMA was something I always wanted to do, but I never had any allusions. I knew I would not be afforded the opportunity to win any championships. For me it was about moving the needle. And that was important enough for it to be documented.

You indicate in the film that being an MMA fighter was one way of “reclaiming” your body. It provides a “measure of control.” Can you talk about that?

It’s doing it on my terms. The environment that I grew up in, I did not have control over my body. Being a victim of childhood sexual assault, and being physically and emotionally abused and neglected by my family, I felt there was no “out.” When I joined the army, I had competing pressures of my parents saying, “It’s better for you to die at war than transition,” and part of me was hoping that [the Army] was some kind of way out. It says something that the people I met in the army had the most progressive politics of anyone I’d ever met at that point. Growing up in rural South Carolina, I didn’t have much exposure to better ideas and better politics. When I say it was a way to “reclaim and reinhabit my own body,” I’m someone who has a long history of having violence done to me. When I was in the army, I was doing violence on behalf of a government that doesn’t give a shit about me. When you are in the military, you have signed your life away. You can disobey an order, or not show up for work, but you go to prison. MMA and martial arts in general provided me a way to interact with my body on terms I could understand and gave me a measure of control I felt I didn’t otherwise have.

I appreciate you wanting to be the best fighter, as well as wanting to be the best soldier when you joined the U.S. Army Special Forces. What observations do you have about LGBTQ folks having to overachieve to prove their value?

No one goes into a fight wanting to lose. That was part of my upbringing. I was expected to be able do everything right the first try. That is the same standard in Special Forces. They say, “See one, do one, teach one.” The expectation is you see something done once, you perform task perfectly the first try, and after doing it once you should be able to teach someone to do it. This goes for everything from shooting a pistol to performing an amputation. That’s the standard. It was easier in the army because there were set tasks, conditions, and standards. Whereas in my upbringing, I had to be a psychic and somehow anticipate my dad’s wants and needs. That idea of perfectionism of wanting to be the best at what you are doing can lead to a lot of toxic places. But for better or worse, I do feel driven to excel.

Going into the MMA world, you had a target on your back from the start. What were your thoughts about being asked and participating? Did you feel tokenized?

I did feel that might have been the case, and to some extent, I still kind of do. The discourse around trans women in sports is so toxic at this point that nobody wants to touch it.

Did you feel ready to face the detractors?

I think I was as prepared as I could be. I knew what was coming and I think I had a better idea of that than Campbell and Combate did. Nothing came at me that I didn’t already expect. I wish things were better. Campbell often accuses me of being pessimistic, but I think I have a very ground level view of where things are.

Do you see any hope?

I do. I am a little bitter that things aren’t going to be as hopeful as I would like at a time that I could take advantage of it. Being completely selfish, it upsets me that I never got the opportunity to be a UCF champion.

The mental toll must be exhausting. You have the extra burden of hate you have to fight. Can you talk about this?

I never really had a choice. Either I was going to be resilient, or I was going to die. Like many other queer and especially trans kids from my generation, I attempted suicide. The army was one big passive suicide attempt. I learned early on that my parents’ love was conditional on me being someone else. My military service required me not only to perform the way that I did, but also lie every day about who I was. I was in under Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. I had the added burden of having to keep the biggest secret in my life from everyone that I knew in addition to having to outperform 99% of my peers to be in Special Forces. I’ve adapted to dealing with those kinds of stresses. I definitely struggle — there is a mental toll — but given my visibility and the sort of people that are against me and the queer community in general, I don’t have luxury of expressing that sort of vulnerability.

You have become an activist, carrying the trans flag out into the ring at your match, and you are seen wearing a shirt that reads, “End Trans Genocide.” Can you talk about being a role model for the trans community and what that involves?

It feels ironic that I was able to lean into that kind of self-expression post-transition. Before I transitioned, the kind of masculinity I was raised in and expected to uphold, there could be no room for femininity and no question of femininity. A guy can’t walk into a Victoria Secret with his girlfriend. You can’t touch a purse—it would un-man you. It’s deeply ironic to me that since I’ve transitioned, I fully embrace my womanhood. Now I can continue riding motorcycles, and training in mixed martial arts. It was freeing in a way I never thought possible.

Watching you fight is very intense and exciting. What do you think when you watch the footage from your bout now?

It’s very easy to pick apart every little mistake—and I made a ton of them. I’m a little bitter because if I were not trans, this fight would be celebrated as a great back and forth between two people absolutely beating the shit out of each other. I have a tendency to lead with my face and I got rocked early on. Unfortunately, my instincts for self-preservation are skewed or damaged. When [Celine] almost knocked me out, instead of thinking I need to cover up, I was thinking I need to knock her out before she knocks me out.

What is next for Lady Feral?

I’m still training and actively looking for fights. The only offers I have gotten have been deeply unserious. Or I get challenged by men who never show up but always have a lot to say.

“Unfightable” | Directed by Marc J. Perez | Opening September 13 at the Village East Cinema | Distributed by Fuse Media and La Jaula Studios.