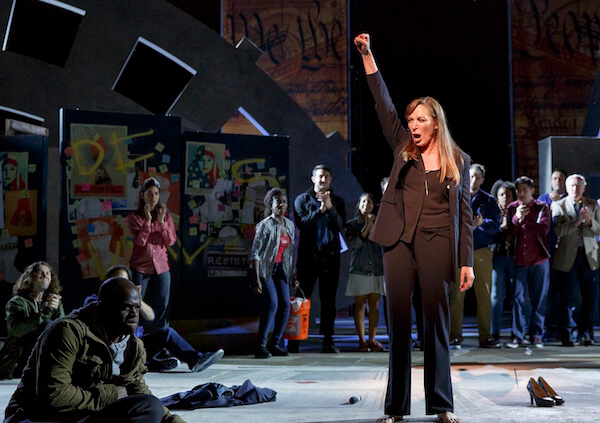

Elizabeth McGovern, Brooke Bloom, and Charlotte Parry in J.B. Priestley’s 1937 “Time and the Conways,” directed by Rebecca Taichman at the American Airlines Theatre. | JEREMY DANIEL

BY CHRISTOPHER BYRNE | If we could understand time in a non-linear fashion, how would that change our lives and choices? That’s the question posed by “Time and the Conways,” J.B. Priestley’s 1937 play now getting a sublime and gorgeously heartbreaking production at the Roundabout.

Taking place in 1919 and 1937, it chronicles a family between the World Wars and their move from giddy affluence to gritty reality. Priestley was inspired by the recent discovery of the theory of relativity and popular notions of time, which suggested that while we experience time as sequential, all times exist at once.

One needn’t understand any of that, however, to be deeply affected by this dark drawing room comedy. Its clear message is that we must be mindful of the present and engage in life as it is if we’re to have any hope for the future. The often-clueless Conways end up chewed up by the world, while the outsiders and realists manage to survive.

J.B. Priestley toys with time at Roundabout, while love takes a beating in two shows at the Public

Directed by Rebecca Taichman with deep sensitivity and precision, the play slowly reveals itself, just as life does. There are elements of magical realism — a literary form for which Priestley was something of a forerunner — that give the piece an unusual poetry. For all the seeming superficiality, the characters are subtly but beautifully drawn so that by the end their human tragedy is deeply moving.

Taichman’s direction is reinforced by the surprisingly affecting set by Neil Patel and a company that is superb. Notably, Elizabeth McGovern as the family matriarch is wonderful. She shows a rage and focus that ground the play and precipitate the family’s demise. Charlotte Parry as Kay gives an intricate performance that is often quiet but creates a felt presence throughout. Gabriel Ebert is terrific as the son who has never achieved his mother’s ambitions but is a man nonetheless content with his life. Perhaps the most unexpected and dynamic performance comes from Steven Boyer, late of “Hand to God.” The outsider who has married into the family, he is the one who finds success because he takes on the world as it is.

As humans, we struggle to understand time and our relationship to it, to peer ahead into the future or gaze back to reshape our past. We’d be better to live consciously in the present knowing that our actions today will shape the future. We owe it to ourselves to make time to see this.

A powerful man requires sexual favors from a vulnerable, less powerful woman as a condition of her getting something she wants. Given the current Hollywood scandals as well as the predator-in-chief in Washington, this year’s spate of productions of “Measure for Measure” couldn’t be timelier. Shakespeare’s tale of cynical, self-serving people in power and their moral posturing has seldom seemed more relevant, though it’s grim to recognize the persistence of such abuses over more than four centuries.

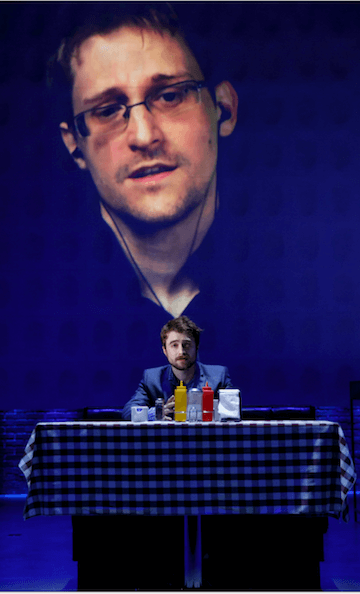

Pete Simpson in the Elevator Repair Service production of Shakespeare’s “Measure for Measure,” at the Public Theater through November 12. | RICHARD TERMINE

In the Elevator Repair Service’s scattered, unfocused, and virtually incomprehensible attack on this play, however, it is Shakespeare himself who is the abuse victim. Trimmed to just over two hours, the manic production races through the text with little poetry and less substance. The company is noted for its literal readings of literature, which has been intermittently entertaining. Here, however, the characters are undeveloped, the staging makes little sense, and it’s clear that director John Collins is more dedicated to applying his trademark “experimental” technique than to respecting or even understanding the play. The result is mechanical, confusing, and frustrating.

The set is a configuration of tables with candlestick phones. Why? Unclear. The production’s primary physical element is the projection of the text on screens. This is helpful because the actors speak so fast and often without any idea of what they’re saying that the projections are vital supertitles to help the befuddled audience. The staging includes actors leaping around for no apparent reason.

The story concerns Angelo, stepping in for the Duke who appears to have left but is actually observing his country disguised as a monk. When Angelo sentences Claudio to death for having sex before marriage, Claudio’s sister Isabella pleads for lenience. Angelo responds that if she’ll sleep with him, he’ll let Claudio live. Isabella and the disguised Duke create a strategy to catch Angelo in his own snare, which goes off well. When Angelo doesn’t keep his end of the deal, the Duke is revealed, Angelo exposed, Claudio ultimately saved, and Isabella’s virtue remains intact.

One only knows this from previous readings of the play. In this production, the whole matter is very hard to follow. One also wonders how Elevator Repair Service gets away with this mess. The company has been a darling of critics for some reason, and the prevailing sentiment today is that “when you’re a star, they let you do it.”

“Tiny Beautiful Things” now at the Public is like a gift. More accurately, it’s like a gift shoppe (spelling intentional). From the outside it looks charming, appealing even, but once inside one is quickly overcome by the sickly sweet odor of potpourri and the growing realization that most of the goods are largely pointless, useless, and cheaply made.

Natalie Woolams-Torres and Nia Vardalos in “Tiny Beautiful Things,” based on the book by Cheryl Strayed, adapted for the stage by Vardalos; and directed by Thomas Kail,” at the Public Theater through December 10. | JOAN MARCUS

The play, adapted from a best-selling collection of letters from an online advice column, attempts to bring these letters to life. Three actors float around the set and intone the letters while Sugar, the name under which the author Cheryl Strayed wrote, gives answers. The letters are the standard, agony aunt fare that has been the staple of this form from the fictional Miss Lonelyhearts to the very real Ann Landers — “love, life, anguish, angst” to quote the musical “Nine.” The answers often veer off course so that Sugar can talk about herself. Sugar maintains that she is not a professional, and that certainly shows. Her replies are often stories about herself and her heroin-addicted, promiscuous past presented in an orgy of humble bragging that’s supposed to inspire her readers to get through whatever challenges they face. Alternatively, she indulges in the kind of peppy, kitten poster sentiment, the therapeutic value of which is “keep your sunny side up.” Sorry to say, but Sugar’s not that interesting, and life isn’t that easy.

Director Thomas Kail does the best he can with the material. The set-up is inherently false as we watch Sugar putter around a kitchen and modest home (set by Rachel Hauck) as she composes her answers. Watching someone write is boring, so all the activity is intended to show Sugar as a regular wife and mother getting lunch for her kids or picking up after her family while the phantom letter writers move about in the clutter. Nia Vardalos, who adapted the book and appears as Sugar, is a generous actress and consistently appealing, but empathy is a hard emotion to play convincingly, particularly for so long when there’s little else going on. Tedium and predictability settle in early.

What Vardalos fails to understand is that a casually read column or a book kept by the toilet cloys and curdles when extended to 90 minutes of cheap emotion and self-aggrandizement. Other than the recitation of some of the comments from the blog posts, there are no outcomes from Sugar’s — ahem — wisdom, so the piece is dramatically dull. It’s a collection of precious moments, which like the eponymous figurines, are more saccharine than enlightening, and one can’t wait to flush and get back to the real business of getting through life the best we can.

TIME AND THE CONWAYS | American Airlines Theatre, 227 W. 42nd St. | Tue.-Sat. at 8 p.m.; Wed., Sat. at 2 p.m.; Sun. at 3 p.m. | $39-$149 at roundabouttheatre.org or 212-719-1300 | Two hrs., 15 mins., with intermission

MEASURE FOR MEASURE | Public Theater, 425 Lafayette St., btwn. E. Fourth St. & Astor Pl. | Through Nov. 12: Tue.-Sat. at 7 p.m.; Sat.-Sun. at 1 p.m. | $75 at publictheater.org or 212-967-7555 | Two hrs., 10 mins., no intermission

TINY BEAUTIFUL THINGS | Public Theater, 425 Lafayette St., btwn. Fourth St. & Astor Pl. | Through Dec. 10: Tue.-Sat at 7 p.m.; Sat.-Sun. at 1 p.m. | $75 at publictheater.org or 212-967-7555 | Ninety mins., no intermission