Human Rights Watch Film Festival has ever-wider scope this year

The unfortunate global state of affairs means that the Human Rights Watch Film Festival will be with us quite a while.

The good news is that the 2004 edition of the annual festival, which runs June 10 through 24, has a wide variety of documentary and narrative films that spotlight with skill and passion human rights abuses ranging from the subtle to the most overt.

Interesting film has been coming out of Iran for the past decade, and since 9/11, we’ve had a couple of years of illuminating Afghani films. Arab and Muslim film is well represented in this year’s festival, with several features examining the trials Islamic women face, often set against larger issues facing the Muslim world.

“The Kite” shows a 16-year-old bride going through Israeli-Lebanese border checkpoints to marry her cousin in a village Israel has annexed, and her eventual relationship with the border guard. “Leila,” from Iran, presents the title character as an affluent but infertile woman whose husband takes on a second wife, allowed under Islam, so that he might have children.

“Paradise Lost” looks at women’s rights in the Arab world with the Israeli/Palestinian conflict as its backdrop. Ebitsam Mra’ana’s film takes us to the director’s village on the Mediterranean coast of Israel, a sole Arab enclave left unscathed by the 1948 war. The village, which is named Paradise, may remain intact, but the town’s psyche is damaged and cowering. Mra’ana skillfully creates a documentary that shows not only her success in getting the men and women of the town to talk, but also captures her from a distance as she conducts her interviews, examining people while being examined. She’s trying to understand the culture of the town, and seeing her in long shot, you realize she’s also part of that village’s culture.

Mra’ana’s world is one in which silence about the Arab-Israeli conflict is the rule. It is also incumbent upon her, as a woman, to “not get involved in politics,” and instead get married and obey her husband. Mra’ana has many opportunities, as an Arab Israeli citizen, to escape small-town rule. She has Jewish friends and she’s fluent in Hebrew and Arabic. And yet, she loves the village and her family, even though her secular ways bother her mother. Her sister wants to be closer to her, but also thinks that’s best achieved if Mra’ana gets married, has kids, and lives nearby.

“We can’t pretend to be Jewish girls or foreigners. Get married, have kids, raise them, that’s our life,” her sister implores.

What makes Mra’ana even more threatening to the town fathers is that she’s asking about history, and particularly, about a woman named Suaad, arrested more than once for simply letting it be known she was pro-Palestinian. Mra’ana ‘s anxieties are existential, as she tries to reconcile tradition versus total personal freedom in a country torn apart by terrorism and second-class status for Palestinians.

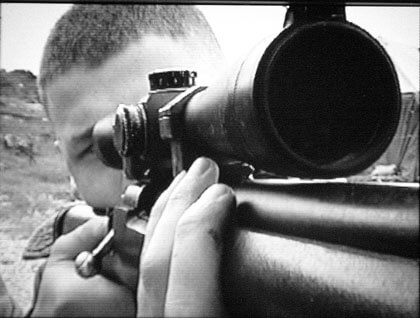

On the other side of the Arab-Jewish divide, “One Shot” looks at the snipers in the Israeli Defense Forces.

The film festival also offers up plenty of evidence of abuses committed outside the Mideast. In “Persons of Interest,” the United States detains Muslims after 9/11, eliminating their most basic human rights, for weeks, months, and in some cases more than a year. The film shows how devastating such detention was both for those jailed and for their families. The advent of digital video makes it easier for small films like this one to be made. The documentary lets those who were dubiously held, and then released for lack of evidence, speak to the camera in a decor-free room.

It’s not exciting editing or directing, but giving voice to those who suffered in this way is a significant achievement by directors Alison Maclean and Tobias Perse.

“Freedom cost me and my family a lot,” says one man, noting he left the West Bank for America to escape the daily struggles for survival.

The testimonies presented in the film have a common thread: What happens next? For many, it meant families being split up, not only by the detentions, but also by deportation. Thousands were rounded up in the biggest criminal investigation in U.S. history, using racial profiling to identify suspects. In some cases, a husband was deported to one country, a wife and the children to another. The horrifying punch line in a number of cases presented is that the detainees were never found to have done anything wrong.

“Deadline” shows how flimsy prosecutions led to many innocent men winding up on death row in Illinois, and how a journalism class at Northwestern University was able to prove beyond a doubt that three inmates were innocent. In the wake of the Northwestern revelations, George Ryan, who was then Illinois’ Republican governor, commuted the death sentences of all 167 prisoners on death row in that state.

Directors Katy Chevigny and Kirsten Johnson document how some innocent men sat in prison for more than ten years. The directors weave statements by death-row inmates with courtroom scenes, some showing victims’ families making their impact statement, demanding the death penalty. Other families of victims are also presented stating their opposition to capital punishment.

The lives of prisoners, guilty or not, are shown to be dreadful, with torture and bad defense attorneys both all too common. Ryan bucked a strongly pro-death penalty climate in a series of public hearings that won his full attention. At the conclusion of the process, the governor, speaking about the futility of “revenge,” quoted Illinois’ most famous son, Abraham Lincoln, who said, “Mercy bears richer fruits than strong justice.”

Human rights abuses are also examined elsewhere in the world.

“Repatriation” is the story of two North Koreans who suffered torture and years of separation from their loved ones in the hands of the South Korean authorities. “Down the Wire” takes a look at a refugee concentration camp in Australia and the activists behind the fence. “Death Squadrons: The French School” implicates France in the clandestine tactics the Argentine government used against its own citizens during its “Dirty War” that lasted from 1967 through 1983. Big business as an institution increasingly controlling lives globally is the subject of “The Corporation,” which opens in commercial release later this month in New York.

The festival also covers many other topics, including child prostitution, the subjugation of women in cultures worldwide, Mexican immigrants struggling to make it in upstate New York, and the demonization of youth when juvenile offenders with negligible offenses are tried as adults.

Right here in our own backyard, “Saints and Sinners” follows the great lengths two Catholic gay New Yorkers—Vinnie Maniscalco and Ed DeBonis—take to create an authentic wedding mass for themselves. Offering the only gay-specific content in the festival, the film is an upper by comparison. If you weren’t able to see this documentary by Abigail Honor and Yan Vizinberg at NewFest, you’ve got another chance.

Some might ask, “Why is it so important for them to do this, to be Catholic when your Church doesn’t want you?” Maniscalco answers that question by noting that they were baptized and given communion as gay people; why be denied the sacrament of marriage? Pursuing the right to practice religion is a human right, road-blocked here by the Catholic Church’s official objection to gays having any rights as gays at all.