Novelist Wayne Hoffman explores dogma’s dilemmas in “Sweet Like Sugar”

In Wayne Hoffman’s new book “Sweet Like Sugar,” a 20-something graphic artist named Benji Steiner crosses paths with a 70-something Orthodox rabbi named Jacob Zuckerman. Their worlds could not be further apart, yet they are drawn together, first by a health emergency and, later, by intellectual curiosity.

The story of their growing friendship in suburban Maryland –– and the religious dogma that drives them apart –– is the narrative arc of this book, which manages to evenhandedly speak volumes about the mixed blessings of modern Judaism.

Hoffman, a 40-year-old New Yorker who has a second home in upstate Livingston Manor, echoes in his narrative several predecessors from modern Jewish American literature. Like the work of Philip Roth, his tale offers rueful humor about the excesses of family. Like the best of Cynthia Ozick and Chaim Potok, the book ponders a Talmudic-like array of arguments regarding a man standing in opposition to his faith. Like Jonathan Safran Foer and Jonathan Franzen, Hoffman brings a newer generation’s critical eye to analyzing the pros and cons of his millennia-long heritage.

What may startle the reader most, however, upon finishing this satisfying tale, is the author’s pedigree. Hoffman, who has crafted a thorny but endearing story about modern Judaism, is a gay atheist.

Of course, Hoffman did not begin his life as a gay atheist. Quite the contrary.

“I grew up Conservative in the traditional household,” he said in a late summer telephone interview. “We kept kosher, we went to synagogue every week, I was Bar Mitzvah’ed, I went to Hebrew School three times a week, Israel, Jewish summer camp, took JCC classes. It was a traditional household.”

However, when Hoffman left his family and Silver Spring, Maryland suburban life for Tufts University in Medford, Massachusetts, he experienced a life transition: “When I went away to college, I decided I was done with religion. I’m an atheist and it struck me that there was not much point in keeping up observances if I didn’t believe in God.”

Hoffman had, in fact, reached this conclusion, he said, soon after his Bar Mitzvah ceremony. But, living under his parents’ roof, he opted for diplomacy for the intervening years before graduation: “I knew someday I would leave the house and I could do what I wanted –– and that’s what I did. Left the house, stopped eating kosher, stopped going to synagogue.”

At Tufts, Hoffman focused on two goals –– his education and his emerging identity as a gay man. Eventually, he realized that his wholesale rejection of Judaism was only a reaction to the entrenched homophobia of Jewish liturgy, which had made it clear there was no place for homosexuality among the Chosen People.

Hoffman decided to embrace those parts of his religion that nurture him. When he became a Manhattanite, Hoffman would once more celebrate certain holidays from his youth that resonated with both joy and nostalgia –– Chanukah, Purim, Passover.

“I’m still Jewish,” he said, “and the things that have meaning for me have meaning for me for my own reasons, not because a rabbi told me that they’re supposed to mean something. They have meaning because of who I am. And it didn’t involve going back to synagogue, which I never did.”

In “Sweet Like Sugar,” Benji is also a gay man, but hardly Hoffman’s doppelganger. The protagonist was born in 1980, a decade after Hoffman. The author placed the lead character in his mid-20s to allow him the flexibility in values that such an age offers. Benji, Hoffman pointed out, is “old enough to ask the questions, and young enough that he hadn’t yet answered them.”

Benji nonetheless struggles with the role –– at once intimate and displaced –– that Judaism plays in his life as a gay man, especially when Rabbi Zuckerman becomes his friend. (Benji’s mother has no problem with her son’s homosexuality; instead, she is fearful proselytizing Orthodox Jews might try to convert him.) As the interaction deepens between the men, Benji analyzes his own sense of Jewish identity. Why, for instance, does he have a predilection for dating blond, non-Jewish men? Like Hoffman, Benji eventually chooses to embrace those parts of his religious heritage that nurture or please him but not feel compelled to observe all its aspects.

“Saying that you don’t believe in the letter of the law does not mean that none of it can have any meaning,” said Hoffman.

Eventually, Benji tests the fabric of the men’s intergenerational alliance and reveals his sexual orientation to his Orthodox friend. Neither easy answers nor quick reconciliations emerge, to Hoffman’s credit as a novelist, but the developments are emotionally captivating. Benji learns that the rabbi also harbors conflicts with the unyielding tenets of his religion where love is concerned –– in his case, with a woman he met while caring for his terminally ill wife. Both men need to heal from the wounds inflicted by Jewish dogma.

And what of Hoffman’s own current relationship with Judaism? It is, as they say, complicated. For the past decade, the unwavering atheist has drawn a paycheck working for Jewish media –– first, at the august Forward newspaper and, currently, as deputy editor of Nextbook Press, publisher of the Jewish Encounters book series.

“It’s true; I don’t go to synagogue, but I spend 40 hours a week as a professional Jew,” he said. “I have a place in the Jewish community, and this is it.”

Pressed to define himself, Hoffman offered the category “secular-cultural Jew.” Still, “Sweet Like Sugar” is richly threaded with Hebrew observations and prayers, such as Pirkei Avot, Chanukah prayers, and Song of Songs.

Did research for the book require Hoffman to return to synagogue?

No, the author said; he simply drew from deep reserves of memory as a Jewish boy.

“There are things that have always stuck with me, since I was a child,” he said. Hoffman was not only a frequent synagogue attendee, but also a Bible scholar and Hebrew School teacher.

“I knew my stuff,” he emphasized.

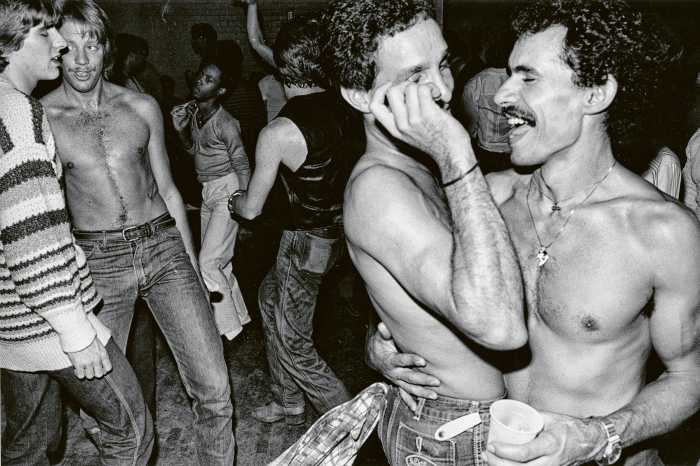

That is not to say that “Sweet Like Sugar” was not a learning experience for him. This novel, Hoffman’s second, is certainly a departure in terms of subject matter from his 2006 debut, “Hard,” a brash, darkly funny tale about creeping conservatism in New York City’s gay community during the 1990s, when sex clubs and bath houses were under fire, often from people within the community.

Neither book is autobiographical, said Hoffman, who has also written for the Washington Post, the Village Voice, the Nation, Billboard, and gay community newspapers.

“‘Hard’ was a more direct translation of real life into fiction and [‘Sweet Like Sugar’] is much more a mosaic interpretation,” he explained. “The bulk of ‘Hard’ is inspired by true events, this is not. This is a novel, first and foremost.”

There is abundant joy in “Sweet Like Sugar,” as Benji revisits his religion, egged on by Rabbi Zuckerman. He takes a stab at dating a Jewish man and stumbles into a one-night stand with a man who sexually fetishizes Jews. (That bitterly funny incident did draw from a real-life experience of Hoffman’s.) Benji eventually finds a place where his dual identities of Jewish man and gay man can co-exist.

The fuzzy optimist might hope that Hoffman attained a similar consciousness during the two years it took to write “Sweet Like Sugar,” but the author, whose personal sensibility tends to steer clear of mushiness, dismissed the notion of a religious rebirth.

Writing the novel “hasn’t altered my relation to Judaism qualitatively, but it has altered the depths to which I can engage or not engage,” he said. “I have access to Jewish books by the thousands [at work]. I’ve always been interested in Jewish literature and read much, much more than I ever did. I wasn’t interested in Jewish observances before, and I’m still not.”

Another reason for keeping his distance, Hoffman said, is that much of Judaism still rejects gay people, even as progress has been made in the last decade.

“But that doesn’t erase the past,” he said. “And it doesn’t erase the past in the memories of a lot of gay people, or people who care about gay people. You don’t wake up and say, ‘Oh, everything’s fine!’ You wake up and say, ‘Okay, I’ll keep that [new attitude] in mind.’”

As for romance, Hoffman’s partner since college, journalist Mark Sullivan, is a blond Irish Catholic.

To support his new novel, Wayne Hoffman plans a book tour, and hopes to appear not only at bookstores, but at Jewish synagogues and religious conferences, as well.

And what of Hoffman’s status as an atheist –– albeit an atheist with a religious novel under his belt?

“Unchanged,” he said. “Very much unchanged.”

Hoffman leads an October 29 Saturday afternoon workshop called “Fact and Fiction: Storytelling for GLBT Jews” at Queer Shabbaton New York, a weekend event sponsored by Nehirim and held at the JCC in Manhattan, 334 Amsterdam Ave. at 76th St. The workshop runs from 1-2 p.m. Complete details at nehirim.org/qsny.

Essentials:

SWEET LIKE SUGAR

By Wayne Hoffman

Kensington Books

$15; 352 pages