Celebrating architecture by invoking the workmanship of filmmaking

In “A House on a Hill,” the film by Chuck Workman now running at Village East Cinemas, the face of Gary Cooper suddenly pops onto the screen without explanation for a few seconds. Cooper is playing the rebel architect Howard Roark who listens with wry pain to a condescending corporate voice telling him that what he should aim for in his work is “a little of the old, a little of the new, the middle of the road—why take chances when you can stay in the middle?”

The clip is from “The Fountainhead,” the 1949 Hollywood whack at the Ayn Rand novel about rugged male individualism that had impressionable females of the era getting the hots and, incidentally, threw Patricia Neal into the arms of Gary Cooper––to her lifelong romantic regret.

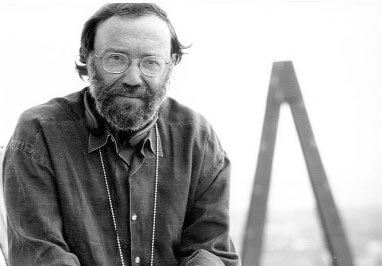

Director/screenwriter Workman, who knows all about film clips––he won an Oscar for putting together 458 of them in 7 minutes for the Directors’ Guild of America––put the Gary Cooper moment into “A House on the Hill” as a joke.

“I knew I had to confront ‘The Fountainhead’ sooner or later because my film’s about an architect,” he said.

Workman perhaps hammers the point home a little too heavily with a verbal reference to “The Fountainhead” later in his own movie.

The Harry Mayfield of Workman’s film, played exactingly by Philip Baker Hall, is a rugged individual all right, but his life is rather more scrambled eggs than omelet. In fact when an artsy young couple go looking for him to design a house for them atop a hill, the only listing for a Harry Mayfield they can find in the Los Angeles phone book is for a bowler of that name.

This is another if somewhat more private joke.

“I know your name,” a fellow once said to filmmaker Workman. “You’re a very famous golfer.” And indeed there is a well-known golfer whose name also happens to be Chuck Workman.

If “A House on a Hill” is in many respects a mirror for the professional life and longings of the man who made it, and who’d felt he’d done “a lot of good work” in motion pictures “but no one knew about it,” the film is sharply different from his domestic life.

Workman and his wife Barbara Klein, a breeder of show horses, are the long-married parents of two and grandparents of another two. Architect Mayfield in the film is long divorced from his wife Mercedes, who––beautifully played by Shirley Knight––runs a very good photography gallery and has an interesting head on her shoulders. She is also, as it happens, partly responsible for the death of their 12-year-old son years ago, when their house, on this same hilltop, burnt down.

There is one other central character: a documentary filmmaker named Gaby, who is rather like Chuck Workman except that she’s a she, and considerably younger, and is played by the always stunning Laura San Giacomo. When Kate, the spoiled client who has hired Harry Mayfield and is now on the verge of hiring Gaby to film the whole process, asks: “Does it have to be like a real movie?” Gaby crisply replies: “If I do it, it does.”

She speaks for Workman. She also speaks for the late Herbert Matter (1907-1984), the Bauhaus-trained artist, designer, painter, teacher, friend of Pollock and de Kooning, and penetrating photographer of Giacometti as well as other great artists.

“When I was 21,” Workman said the other day, “I worked on a movie directed by Herbert Matter’s son, Alex. Herbert Matter and his critic wife lived in MacDougal Alley, but they had a large studio building in the East 30s, and they let Alex use one of the floors for his movie.

“One day as Alex and I and the crew went off for lunch, girls, a good time, all that, I passed a room in which Herbert Matter was lighting a chair for a shot for a Knoll commercial. We all went out for lunch, did our thing, came back hours later––and there was Matter, still fastidiously lighting that chair. I never forgot it, and that was 35 years ago.

“So there’s a little bit of that in Gaby, in the movie, and in Harry Mayfield––someone who just stays with it. I admire that, and wish I were more like that.”

James Karen, somebody who has stuck to his craft for upwards of four decades and can be seen in films about Samuel Beckett and Buster Keaton from the early 1960s, plays an elderly pal of Mayfield’s. The older man gives Mayfield advice on the order of “Do what you have to do, Harry” and rambles on about a sexy girl named Agnes who, it turns out, has been dead 19 years.

“I told him, ‘Jim, you once played a 100-year-old man,’” Workman recalled. “‘Here you’re only playing a 75-year-old man.’ Jim said, ‘I can do that!’”

Workman believes that his old friend Shirley Knight wanted to do the film because of the recent loss of her husband, screenwriter John Hopkins. The character she plays in “House” has lost two husbands, one to divorce, one to death.

Ms. Knight can also be found in “The Actor’s Life,” Workman’s latest output, a documentary.

“Making it,” says Workman, “I learned a lot about actors, and I’ve been working with actors all my life. Make a film about welding, you learn a lot about welding. When I made ‘The Source’ [1999], a film about the Beats, I learned a lot about the Beats.”

It was in the course of shooting “The Source” that Workman one day said to Ed Sanders, leader of the 1960s band called The Fugs, “Hey, you started The Fugs and I went to Rutgers. How did that happen?” To which Ed Sanders replied, “Because you were a Jewish middle-class guy and I wasn’t.”

The Jewish middle-class guy was born in Philadelphia on June 5, 1944, one day before D-Day, the son of a wandering father he associates with the charming rogue novelist whom Geoffrey Wolff wrote about in “The Duke of Deception.” Workman’s stepfather was a Republican judge from New Jersey.

“I was actually raised by my grandparents in Atlantic City. We were privileged, not rich. I went to Cornell, then Rutgers. It was at Cornell that I was first introduced to foreign films. I remember that, on the same day, I saw Visconti’s ‘Rocco and His Brothers’ and Billy Wilder’s ‘One Two Three,’ and was a lot more impressed by ‘Rocco and His Brothers.’”

“Right after Rutgers I came to New York and got into Bergman, Truffault, Godard, that world. When I graduated, it was not quite Vietnam. I joined the reserves and started looking for a job. I didn’t know anybody who worked in movies, ended up doing commercials, and,” said Workman, “was fairly successful at it. Moved to Hollywood when I was 20, again did very well with commercials, and moved into documentaries in the 1980s.”

One of the minor irritating things about “A House on the Hill” is the frequent dividing of the screen into what Workman calls “boxes,” because that’s what they are––inset squares or rectangles of varying sizes and constantly altering dimensions. A sort of focus-on, or iris-in, related to Pablo Ferro’s visual compartmentalization for Norman Jewison that dates back to “The Thomas Crown Affair” in 1968.

“Or for that matter, Abel Gance did it with ‘Napoleon’ [in 1927]. I use it as a metaphor,” Workman said. “Why not? When people are thinking, the frame isolates them. I know there are those who disagree with me, but I think you should do everything you can to make the viewer get and understand the subtext. Godard gave us the hard jump-cut in ‘Breathless.’ The boxes helped me cut within scenes.”

And “A House on a Hill,” one gathers, helped Chuck Workman, so facile (his word), so gifted, in putting together those enormously enjoyable kaleidoscopes for the Academy Awards (“I’m best known as ‘best known for…’”) that helped Workman be the kind of architect he’s wanted to be all his adult life—with film, not beams and cement. But will that house on that hill ever actually get built?