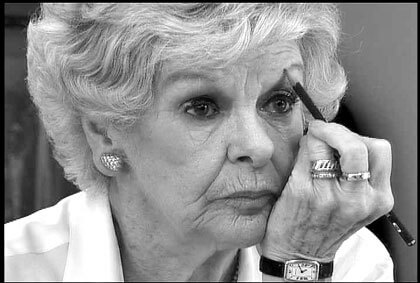

Elaine Stritch, with an upcoming HBO special, on life, love, and liberty

If you haven’t heard Elaine Stritch being Ethel Merman bellowing: “Oh, Elaine, will ya for Chrissake go to New Haven and sing the fuckin’ song!” you haven’t begun to live.

Actually, quite a lot of people heard Stritch do that in her 2002 one-woman Obie- and Tony-winning show, “Elaine Stritch at Liberty,” and a lot more will now get to hear it, and see it, in the blockbuster Pennebaker-Hegedus-Doob documentary of the same title that premieres on HBO at 8 p.m. this Saturday, May 29, with a scattering of replays to follow.

The Merman bellow is the punch line of Stritch’s hysterical retelling of the fortnight five decades ago when, during the blizzard of ‘52, she daily (and twice on matinee days) shuttled, via an ex-boyfriend and his MG, between her assignment as stand-by for Merman in “Call Me Madam” at the Imperial Theater on Broadway and rendering the “piss-elegant” Gypsy Rose Lee-type “Zip!” striptease number in “Pal Joey” at the Shubert Theater in New Haven.

“And you wonder why I drank,” says the woman who fought the bottle, and generally lost, throughout the first three quarters of her long and sometimes dazzling career.

The entire one hour and 45 minutes of the Pennebaker film—it seems like half that—is a lay-it-on-the-line examination of the life and times, breakthroughs and blunders, and most especially the hoarse laughs, of one of the great natural resources of show business today—the good Catholic girl out of Detroit, who at18 fled, undefiled, late one night, from Marlon Brando’s three-flight walk-up in Greenwich Village. “Elaine,” Brando had coldly declared when next they met, “I want two things from you: silence and distance”—only to subsequently apologize, in tears, as he crunched a wine glass in his hand.

This is also the actress whom Noel Coward adored, called “Stritchie,” and took with him for “a weekend in the Berkshires at Alfred and Lynne’s” (aka Lunt and Fontaine).

This is also the actress whose dressing room was invaded one night by Richard Burton, who informed her: “Halfway through your last number I almost had an orgasm.”

And the actress who one night during the Broadway run of William Inge’s “Bus Stop,” answered a ringing backstage telephone. On the other end was Ben Gazzara. He wanted Kim Stanley. He got Elaine.

“He took me to Downey’s Steak House [1950s actors’ hangout, Eighth Avenue and 44th Street] and then took me to my apartment on 52nd Street, and stayed two years.”

Until, in Rome, with Gazzara proposing marriage, her eye fell on a beautifully tall handsome male in a tuxedo coming down a flight of stairs in the Grand Hotel. His name was Rock Hudson.

“Arrivederci, Ben… And we all know what a bum decision that turned out to be,” the actress said.

You will phone Elaine, this journalist was told, at midnight Friday, at the Carlyle Hotel. She’s just back from California that day, and tired.

The operator at the Carlyle put the call through, no questions asked.

“Oh, hello,” said Elaine Stritch. “No, I don’t get my calls announced. I take my chances. Also it seems to me to belittle people to ask who they are. [secretary’s voice] ‘What is your name, please?… Just one moment… I’m sorry, she’s not in.’”

Stritch, in her own caustic-kindly warm-blooded baritone, said. “Well, I don’t do that.”

This is the lady who on taking to the stage of Radio City Music Hall two years ago to accept, at age 76, her long-hungered-for first Tony Award, cut off the cannonading applause of her peers with a crisp, dry: “Don’t take up my time.”

But now, at midnight, on the phone, she had plenty of time.

“Ben,” she said of another survivor, the gravel-voiced Gazzara who gave us such a winning recent Yogi Berra. “Dear Ben. You know what he did? He came back to my dressing room and said: ‘I didn’t know you were that talented.’”

The Pennebaker film—crafted by A.D. Pennebaker, Chris Hegedus, and Nick Doob—is partly the “At Liberty” stage show, partly some bits of a remarkable 1970 Pennebaker documentary of Stritch trial-and-erroring her difficult way into a matchless performance of Sondheim’s “The Ladies Who Lunch” for the cast album of “Company,” and partly new material of Stritch and others talking about, well, Stritch.

Stritch takes credit for the added balance.

“I’m glad I had something to do with it,” she said on the phone. “I was in on the editing. When I saw the rough cut, I thought Pennebaker had left in too much of my show and too much of that [1970] recording performance. Enough already. But you can’t cut out that stuff about Rock Hudson and Ben Gazzara and my dad” (who offered her “a mean whiskey sour when I was 14” but would subsequently one day tell her: “Lainie, you are not the same after two martinis”).

“You know… God, it’s so hard to explain—because, you know, I’ve never [before] seen myself on stage, never seen me on stage, or seen me in a musical, all of a sudden. I don’t have a word for it yet. It doesn’t frighten me,” she said, “but it’s not like a movie where you’re sitting with other people.

“No,” she said, after a contemplative pause, “it’s not like a movie, where you play someone else [i.e., not yourself.] I never talk about ‘technique’ or anything. That bores the shit out of me, and I surf on.”

With a snort:

“Young actors talking about how they ‘approach’ their role. I never talk about ‘a role’…

“But you know, Jerry, this one’s close to the bone. It’s very close to the bone. And you know, it is my life, a good hunk of it anyway. And another thing: here I’m singing these songs, hoping each time I’ll just get through it—and it’s on fucking film.

“Back there when Pennebaker shot that [‘Company’] recording. I didn’t know what was going on. Pennebaker worked the whole thing without any cameras that anyone could see. He sort of sat on the side. I didn’t even know he was there.”

“That’s our Elaine,” said A.D. Pennebaker when apprised of the above. “She takes that stand, and it’s all right. The camera was definitely there and it was kind of big and noisy. The thing was, she’d been in a couple of movies by then, and she was used to the camera being a huge edifice like a statue of Thucydides. If it’s a hand-held camera on somebody’s shoulder, she doesn’t see it as movie-making.

“I think she’s being a little coy. She knows she’s entertaining at a party.”

Hegedus, who is Mrs. A.D. Pennebaker, said: “I think she’s a little more aware of the camera now. She’d direct her whole life for you, if she could. That’s a whole film in itself—editing with Elaine Stritch.”

“Most of the time we don’t invite people into the editing of what we’re filming,” explained Pennebaker, as in, for instance, “The War Room,” an inside view of the 1993 Clinton campaign team. “But with Elaine, you couldn’t bar the door. It was like you’re getting the expert to undo the bomb before it goes off. Even though she drove us crazy, she was 80 percent right. We resisted, but we didn’t begrudge her. She said: ‘This isn’t about me, it’s about comedy,’ and she was right.”

“She has impeccable timing,” Hegedus explained. “She’s an incredibly brave and funny and impossible person. That’s what she’s about, and that’s why people love her.”

“Actors are sort of puppets. Except in my case,” Stritch said during our midnight chat. “D’you know in the show where I talk about telling The New York Times that I was looking for a director who knew more than I did [only to have Hal Prince call and say: ‘Elaine, I know more than you do’]. Well, I meant that. I just lately did a workshop with a certain director … Never again… This person knows less than I do, and I don’t want to go to dinner with someone who knows less than I do.

“No, Ben Gazzara was not my first. I say in the show I was a virgin until I was 30, and when I met Ben I was 33. But I was very, very particular about that kind of thing. If I had any [romantic] connection, it was two years, not two weeks. I don’t even call them affairs. An affair is Acapulco.”

Ms. Stritch, did you know about Rock Hudson, back at the time?

“How could I know? What people knew? I didn’t know anything. Though I guess there were several guys in California who knew, if you know what I mean.”

She was born, she said, in Detroit, Michigan, February 2, 1926.

“I’ll be 79 next February. My father? Why do you want to know that? He was George Joseph Stritch, born 1800-something, and lived to be 96. Was manager of manufacture sales at B.F. Goodrich. Wait, I have his birthday on a prayer card in some book here.”

Scrabbles around. Can’t find it.

“My mother was Mildred Jobe Stritch, and my father called her Midge. I’m Irish on my dad’s side and Welsh on my mother’s. I love the Welsh thing. No, I never drank with Dylan Thomas, but I drank with Hemingway, that’s good enough, and with that great Irish playwright—yes, him, Brendan Behan—and with Tennessee, whom I loved with a passion.”

She is, and for 17 years has been, a Friend of Bill’s, i.e. a recovering alcoholic. Also an insulin-dependent diabetic. The disease almost took her life in a hypoglycemic attack in 1987. A mini-bar waiter at the Hotel Carlyle saved her life.

“It’s damn tough, kiddo. Every time I had a problem, Jerry, I picked up a drink.”

Now, having done everything else, she’s thinking of doing cabaret.

“And I’m hoping and praying I can do a new straight play. I’d sure like another ‘A Delicate Balance’ thrown my way.”

Edward Albee, are you listening?

The clock was getting on to half-past midnight.

“I’m always in late at night,” said Elaine Stritch. “Call me if you need to know anything. Stay safe. See you soon.”

The future may hold whatever it will, including, one hopes, a delicate or an indelicate balance, but this is one human being who is always going to be at liberty.