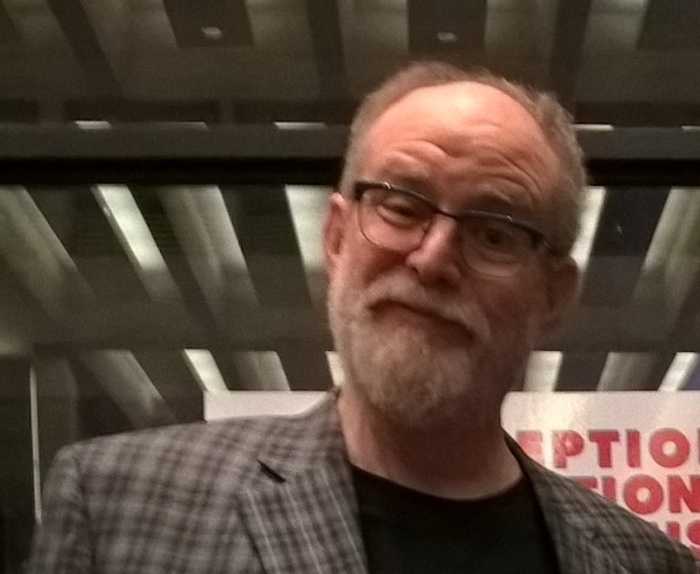

Last week Wednesday, just as Gay City News was going to press, the announcement reached our team that bell hooks (née Gloria Jean Watkins), groundbreaking Black feminist scholar, poet, and cultural critic, was dead. She was 69 and the cause of death was renal failure. She died at her home in Berea, Kentucky, the state of her birth, where, since 2004, she was the distinguished professor-in-residence in Appalachian Studies at Berea College. Exceptionally prolific, hooks authored close to 40 books across the course of a career as an academic and public intellectual that spanned over four decades, during which she held professorships at Oberlin, Stanford, Yale, and the City University of New York. Committed to resisting, through both her prose and practice, what she famously called “white-supremacist-capitalist-patriarchy,” hooks introduced a style of writing and, in her words, critical apparatus, that widely influenced or engaged successive generations of scholars, writers, artists and activists. In the following personal essay, Gay City News contributor Nicholas Boston, a professor of media studies at the City University of New York, reflects on the legacy of bell hooks.

When I learned of the passing of bell hooks, I felt an immediate pull to the persons, places, and spaces that I was getting to know at the time that I was arriving at her work. I searched my playlists for music from that time — Brand New Heavies, Digable Planets, Young Disciples — tunes I hadn’t heard in years. This reaction wasn’t nostalgia, it was mourning — so much of that period was infused and enmeshed with bell hooks.

I found my on-ramp to the then superhighway, now classic grand boulevard, that is hooks’ oeuvre on February 6, 1992. On that evening, she gave a talk at Simon Fraser University, in Vancouver, Canada. Then a professor at Oberlin College, she had already published five books, including “Ain’t I a Woman?: Black Women and Feminism,” and “Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black.” Listening to that talk now, hooks’ prescience is astounding to hear. The internationally televised hearing of law professor Anita Hill’s accusation of sexual harassment against Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas had recently transpired and in the preamble to her talk hooks commented on it. “On one hand, we had this Black woman who will go down in history in many ways as the most visible, the most represented, Black woman,” she said. “At the same time, … I heard so many white women, particularly, saying, ‘She was me!’”

From there, hooks proceeded to the point. “I have a new book coming out called “Black Looks: Race and Representation” that the talk I’m going to use tonight comes out of,” she said. When she spoke the title of the talk, “Madonna: Plantation Mistress or Soul Sister,” now the hotly debated Chapter 10 of that book, the audience roared.

Now, here’s the truly relevant and remarkable part of my recollection: I was not physically present for this talk. But its social and cultural aftershocks were so lasting, so transformative, they met me months afterwards. For on that occasion, when bell hooks looked out at the packed auditorium anxiously awaiting her talk, she was dismayed at the sight. There were people standing or unable to enter due to fire regulations. She told the organizers to announce that any white person seated should get up and give their place to the nearest person of color who was standing or couldn’t get in at all. If those present were truly familiar with her writing and teachings on such topics as access, accountability, appropriation, privilege and patriarchy, they would not think twice. But, of course, people did think twice, and many more times, and they were still thinking and talking about having their politics wrenched from theory and plonked into practice when persons who’d been in that auditorium, faced with that request as either sitters or standers, became my friends, lovers, collaborators, co-authors, and, yes, even nemeses.

I might have encountered bell hooks’ work a couple years prior to this, during my first, aborted attempt at an undergraduate career at Dartmouth College, in New Hampshire. But, so distracted a student was I that all I can recall now, vaguely, is her name in a line on a syllabus. My passions were music, fashion, film, mass media, club culture, and bodies — my own and other guys’ — which commanded my full attention. I dropped out of college and soon landed in Vancouver, where I knew nothing and nobody and my life could feel more like an immersion than an intermission.

The spring came. I was on my way back from an excursion to the cruisy trails at Wreck Beach, having scambled up a perilous escarpment attemptable only by the under-30 set. Hopefully, the queer-positive Vancouver City Council has since put in stairs — I would break my neck on that 90-degree slope today. Anyway, there I was, standing at a bus stop with nothing to do but look around, these being the days before cellphones. A flyer adhered to a pole caught my eye. It might have been for a concert or performance or who knows what, but I wanted the information on it, so I proceeded to peel it off gingerly. I had just about managed to get it unstuck when over my shoulder came a young woman’s voice in mock admonishment, “Whose voice are you trying to silence, brother?!” It was Lydia Masemola, a year my junior at 22, energetic, fit, working in community radio. Our friendship started from there and through her I integrated into a network of cultural producers, as hooks would say, many of whom had been in that auditorium, all of whom were thinking seriously about hooks’ work and how it applied to them and their agency to put representations into the world.

“Blessings to our new ancestor, sister bell hooks, she’s still doing the work,” Lydia said to me last week in a WhatsApp voice message sent from her home in Johannesburg, South Africa. “It was a really special time, eh? And, I think it was so critical for our future endeavors, our lives. It really set the stage for us. You don’t get that type of perfect scenario where you meet a variety of Black people, and people of color, and white allies who all have very progressive ideas and want to make changes in the world. A lot of what we worked on feels like it was a waste of time, in a way, because look at the world now. But, not only were we politically feeding each other, but also socially. Oh my Lord, I remember those dancehall parties, woo! It was good times, I tell you!”

Bell hooks took theory out of the books and put it in the barbershops and beauty salons. A polyglot, she spoke many languages — Academese, African American Vernacular English (AAVE), CUSS, WASP — cross-pollinating amongst them. In her prose, instead of referring to people as “populations” or “demographics” or any other word in the sociological lexicon, she used “folks.” Just folks. It was a throwback to the use of the word by her literary forebears W.E.B. Du Bois (“The Souls of Black Folk” [1903]) and Langston Hughes (“The Ways of White Folks” [1934]), but also her biological/communal forebears. She adopted the name “bell hooks,” always in lowercase letters, “based on the names of her mother and grandmother, to emphasize the importance of the substance of her writing as opposed to who she is,” according to her faculty page at Berea College.

I look at my own first published piece of “theory” — a rather overwrought cri de cœur against the ubiquitous homophobia of heterosexual Black male performers published in 1993 in the first edition of a magazine called “Diaspora” created by Peter James Hudson — and I see bell hooks writ large all over it: the interweaving of tongues, the finale imploring love and solidarity.

The title is classic hooks: “Brothas Gotta Work it Out! Roots, Culture, & SM Domination.” It was one of my greatest joys to learn years later that hooks saw the magazine in New York and said she’d appreciated the piece.

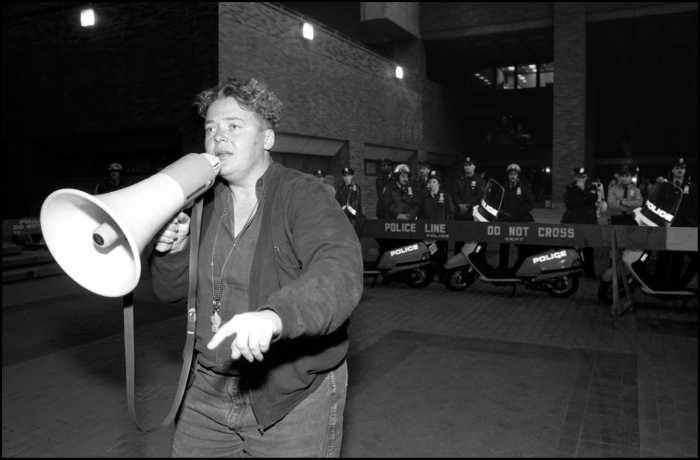

I came to New York City a year later. One afternoon at dusk in the fall of 1994 I was walking up Christopher Street and happened to witness a clamorous group of guys, not too much younger than me, sauntering past the PATH train entrance, which at that time had cops posted outside. I was walking on the opposite side of the street, holding myself stiffly accountable to my internal monologue of respectability politics that said, “Don’t be too loud; don’t flit or flaunt; straighten up that walk.” As I looked over, the ringleader of the group spontaneously broke into a noisy rendition of rapper KRS-One’s track “Sound of da Police” and dipped down to give a little flirtatious dance in front of one of the officers, a handsome Latino man who smiled with bemused exhaustion. The dancer’s acolytes erupted in hoots and hollers and one yelled, “Teach!” to which another followed up with, “Yes, Miss Thing, teach to transgress!”

And this is what I mean about how everything was enmeshed — place, space, language, concepts, culture, bodies — and how bell hooks was one of our sharpest needles.