In recent years, the process for transgender people getting new birth certificates showing their new names and changing their sex designation to coincide with their present gender identity has become routine in many places, and in the rare cases where trial judges have balked at making the changes, appellate courts have frequently reversed their decisions and ordered the change.

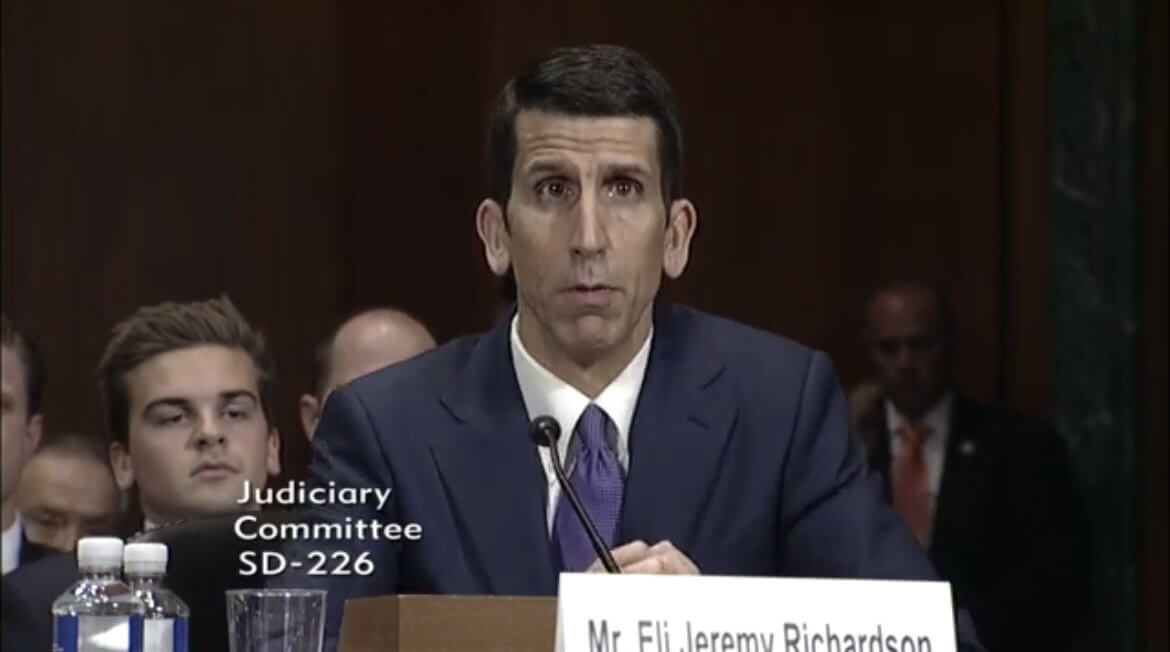

But a decision by Trump-appointed US District Judge Eli Richardson of the US District Court in Nashville, Tennessee, takes a distinctly different view. In a hyper-dense opinion running more than 28,000 words, on June 22 Judge Richardson rejected a constitutional attack on one of the few state laws to explicitly bar changes on birth certificates to reflect gender transition.

A Tennessee statute states that “the sex of an individual shall not be changed on the original certificate of birth as a result of sex change surgery.” Tennessee officials have interpreted that to mean that the original birth certificate must stand unaltered as to its sex designation, even when the person whose birth is recorded no longer identifies with the sex indicated on the certificate.

Many other states, responding to changing social understanding about gender identity, have dispensed with any requirement for proof of surgical alteration to change the sex designation on a birth certificate, and some now even dispense with a requirement for a doctor’s statement that the individual has undergone some unspecified kind of medical treatment for transition, but not Tennessee.

In Gore v. Lee, his decision on a challenge brought by Lambda Legal on behalf of a transgender person who was denied the requested changes, Judge Richardson engages in a hair-splitting farrago of sophisticated deconstruction of the plaintiff’s complaint. His starting point and ground zero is his contention that the state may treat the birth certificate as a record of a historical event based on what was known at the time of birth. The physician submits to the state a report of the birth and reports the sex based solely on visual observation of genitalia on the newborn. As far as the state is concerned, that is a historical record that cannot be retroactively altered unless it is shown to be “incorrect” and the state does not consider it to be incorrect as a result of somebody transitioning years later. The state argues that a birth certificate is not intended to say anything about the individual other than what was recorded at the time of birth.

Thus, Judge Richardson rejects the plaintiffs’ suggestion that they are asking for a “correction” because now the word recorded on the certificate does not represent their current understanding of who they are. Judge Richardson insists that is not the purpose of a birth certificate.

Many other courts have ruled on this issue in recent years, recognizing that on those relatively rare occasions when one needs to show a birth certificate, usually to establish place of birth (for citizenship purposes) or age (for getting a driver’s license, for example), having a certificate that doesn’t reflect the person’s current name and sexual designation can be problematic. For one thing, it “outs” the individual as transgender when the certificate says “M” and the person presents as “F” (or vice versa) or as non-binary. Many other agencies have managed to adjust to the situation — although not always without a struggle — but even in Tennessee today, a transgender person can get a new driver’s license consistent with their gender identity, a transgender person can get a new passport from the US State Department, and, although it is a continuing struggle, some people have succeeded in getting new diplomas issued by educational institutions.

For another thing, the very existence of the birth certificate is a psychological speed bump in the transitioning process. A change is part of the ratification by the government recognizing the gender identity — characterized by the plaintiff in this case as the “true sex” of the individual.

Judge Richardson pounces on what he sees as inconsistencies in the plaintiffs’ arguments. He notes that plaintiffs have acknowledged that “sex” and “gender identity” are distinct concepts, and that in the important Supreme Court decision of Bostock v. Clayton County, Justice Neil Gorsuch began his analysis with the concession by all parties that the word “sex” in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 means “biological sex,” which is construed to be the sex consistent with the natal observation of genitalia, although the Court concluded that it is impossible to discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or transgender status without discriminating, at least in part, on the basis of sex, because the “biological sex” of the individual is a necessary component of analyzing the question of discrimination because of sexual orientation or transgender status.

Judge Richardson asserts that the sex designation on the birth certificate is intended by the state to be a record of “biological sex,” so a request to “correct” it by changing it to accord with the individual’s later-discovered gender identity is not a “correction” at all — the original designation is already and remains correct as a statement of historical record (and, he adds, remains correct as a matter of genetic sex even after medical/surgical transition). He insists that the state’s refusal to change that marker is not making any sort of statement or representation about an individual’s gender identity, just about their “biological sex.”

If it sounds like he is playing word games, one must remember that dissenters from the Bostock decision accused the Supreme Court majority of playing word games as well.

In cases from other jurisdictions, some courts have given weight to the evidence that states allow for significant changes in birth certificates in acknowledging later-occurring events. In child adoption cases, for example, they will issue new birth certificates showing the names of adoptive parents and the new name, if any, of the adoptee. For such individuals, their new birth certificate is no longer a “true record” of the names of their parents and of them when they were born, and the state is not troubled by this. Why should the sex designation be any different?

Judge Richardson rejects the argument that allowing such changes for adoptions but not for gender transitions presents an equal protection problem. He rejects the contention that state insistence on the original sex designation being permanent and immutable adversely affects the liberty interest of transgender people in violation of substantive due process. He asserts that a discordance between what it says on their birth certificate and how they are living their life years later is not a rejection by the state of their gender transition — and cites Tennessee’s practice regarding drivers’ licenses as proof against anti-trans bias. And he rejects the contention that there is any “compelled speech” issue when a trans person who needs to present a birth certificate receives a glance from someone who might think — if not say out loud — “you are transgender.” The judge belittles the asserted harms argued by the plaintiffs; dismisses the fact that Tennessee has not shown that there is any particular need for the state to keep the original, now-obsolete, sex designation; and rejects the idea that the state can alternatively keep the original birth certificate in a sealed record if it has some need to track sex designations of births (although no such need was demonstrated in the argument of this case).

Indeed, in an age of electronic databases of vital records, it would seem easy to store the old information as well as the new without altering physical documents at all. The state could store the original information in a “sealed” file and produce prints of the revised information on demand, making it possible to do the kind of statistical analysis of births mentioned by the judge while at the same time satisfying the human needs of a transgender person for a birth identification document that doesn’t “out them” as transgender and visibly affirms their identity as recognized by the state.

The judge’s opinion can be appealed to the Sixth Circuit, which has a fairly good record on transgender issues in recent years. Rethinking of this decision is certainly in order.