Jameka K. Evans. | LAMBDA LEGAL

The US Supreme Court announced on December 11 that it will not review a decision by a three-judge panel of the Atlanta-based 11th Circuit Court of Appeals, which ruled on March 10 that a lesbian formerly employed as a security guard at a Georgia hospital could not sue for sexual orientation discrimination under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

The full 11th Circuit denied a motion to reconsider the case on July 10, and Lambda Legal, representing plaintiff Jameka Evans, filed a petition with the Supreme Court seeking review on September 7.

At the heart of Lambda’s petition was an urgent request to the Court to resolve a split among the lower federal courts and within the federal government itself on the question whether Title VII, which bans employment discrimination because of sex by employers that have at least 15 employees, can be interpreted to ban discrimination because of sexual orientation.

Whether Title VII covers sexual orientation discrimination unlikely to be aired in 2017-18 term

The impact on Evans herself of the court’s refusal to take up her case may not be decisive since she remains free to pursue her discrimination case on a different legal theory, but for now at least the high court is standing back from deciding a key issue regarding LGBTQ rights.

Nobody can deny that members of Congress voting in 1964 were not thinking about banning sexual orientation discrimination at that time, but their adoption of a general ban on sex discrimination in employment has been developed by the courts over more than half a century to encompass a wide range of discriminatory conduct reaching far beyond the simple proposition that employers cannot discriminate against an individual because she is a woman or he is a man.

Early in the history of Title VII, the Supreme Court ruled that employers could not treat people differently because of generalizations about men and women, and by the late 1970s had accepted the proposition that workplace harassment of women was a form of sex discrimination.

In a key ruling in 1989, the high court held that discrimination against a woman because the employer considered her inadequately feminine in her appearance or behavior was a form of sex discrimination, under what is known as the sex stereotyping theory, and during the 1990s the Court ruled that a victim of workplace same-sex harassment could sue under Title VII, overruling a lower court decision that a man could sue for harassment only if he was being harassed by a woman, not by other men.

In that latter decision for a unanimous court, Justice Antonin Scalia opined that Title VII was not restricted to the “evils” identified by Congress in 1964, but could extend to “reasonably comparable evils” to effectuate the legislative purpose of achieving a non-discriminatory workplace.

By the early years of this century, lower federal courts had begun to accept the argument that the sex stereotyping theory provided a basis to overrule earlier decisions that transgender people were not protected from discrimination under Title VII. There is an emerging consensus among the lower federal courts, bolstered by rulings of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) as early as 2012, that gender identity discrimination is clearly discrimination because of sex, and the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals several years ago embraced that view in a case involving a transgender woman fired from a research position at the Georgia legislature.

However, the idea that some variant of the sex stereotyping theory could also expand Title VII to protect lesbian, gay, or bisexual employees took longer to emerge. It was not until 2015 that the EEOC issued a decision concluding that sexual orientation discrimination is a form of sex discrimination, in part responding to the sex stereotyping decisions in the lower federal courts. And it was not until April 4 of this year that a federal appeals court, the Chicago-based Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, approved that theory in a strongly worded opinion by a decisive majority of the entire 11-judge circuit bench, just a few weeks after the 11th Circuit panel ruling in the Jameka Evans case.

Writing for the Seventh Circuit, Judge Diane Wood said, “It would require considerable calisthenics to remove the ‘sex’ from ‘sexual orientation.’”

The 11th Circuit panel’s 2-1 decision to reject Jameka Evans’ sexual orientation discrimination claim seemed a distinct setback in light of these developments.

However, consistent with the 11th Circuit’s prior gender identity discrimination ruling, one of the judges in the majority and the dissenting judge agreed that Evans’ Title VII claim could be revived using the sex stereotyping theory based on how she dressed and behaved, and sent the case back to the lower court on that basis. The dissenting judge would have gone further and allowed Evans’ sexual orientation discrimination claim to proceed under Title VII. The other judge in the majority strained to distinguish this case from the circuit’s prior sex stereotyping ruling, and would have dismissed the case outright.

The Seventh Circuit’s decision in April opened up a split among the circuit courts in light of a string of rulings by several different circuit courts over the past several decades rejecting sexual orientation discrimination claims by gay litigants, although several of those circuits have since embraced the sex stereotyping theory to allow gay litigants to bring sex discrimination claims under Title VII if they could plausibly allege they suffered discrimination because of gender nonconforming dress or conduct.

Other courts took the position that as long as the plaintiff’s sexual orientation appeared to be the main reason why they suffered discrimination, they could not bring a Title VII claim.

In recent years, several federal trial judges have approved an alternative argument: that same-sex attraction is itself a departure from widely-held stereotypes of what it means to be a man or a woman, and thus that discrimination motivated by the victim’s same-sex attraction is necessarily a form of sex discrimination under Title VII. Within the New York-based Second Circuit, several trial judges have recently embraced this view, but three-judge circuit panels consistently rejected it.

Some progress was made this past spring, however, when a three-judge panel in Christiansen v. Omnicom Group overruled a trial judge to find that a plaintiff whose sexual orientation was clearly a motivation for his discharge could bring a sex stereotyping Title VII claim when he could plausibly allege behavioral nonconformity apart from his same-sex attraction.

More recently, the Second Circuit agreed to grant en banc reconsideration by the full circuit bench on the underlying question and heard oral argument in September in Zarda v. Altitude Express about whether sexual orientation discrimination, as such, is outlawed by Title VII.

Zarda involves a gay male plaintiff whose attempt to rely alternatively on a sex stereotyping claim had been rejected by the trial judge in line with Second Circuit precedent. Plaintiff Donald Zarda died while the case was pending, but it is being carried on by his estate. Observers at the oral argument thought that a majority of the judges of the full circuit bench were likely to follow the lead of the Seventh Circuit and expand the coverage of Title VII in this circuit, which covers Connecticut and Vermont as well as New York. Argument was held more than two months ago, so a decision could be imminent.

The late Donald Zarda, a skydiving instructor whose estate has gone before the Second Circuit Court of Appeals' full bench to make its case that the late skydiver sexual orientation discrimination suit brought after he was fired by Altitude Express. | FACEBOOK.COM

Much of the media comment about the Zarda case, as well as the questioning by the judges, focused on the spectacle of the federal government opposing itself in court. The EEOC filed an amicus brief in support of the Zarda Estate and sent an attorney to argue in favor of Title VII coverage. The Justice Department filed a brief in support of the employer and sent an attorney to argue that the three-judge panel had correctly rejected the plaintiff’s Title VII claim. The politics of the situation was obvious: The Trump appointees now running the Justice Department had changed DOJ’s position (over the reported protest of career professionals there), while the holdover Obama majority at the EEOC was standing firm by the decision that agency made in 2015. As Trump’s appointment of new commissioners changes the EEOC’s political complexion, this internal split is likely to be resolved against Title VII protection for LGBTQ people.

This is clearly a hot controversy on a question with national import, so why did the Supreme Court refuse to hear the case? The court does not customarily announce its reasons for denying review — and did not do so this time. None of the justices dissented from the denial of review, either.

A refusal to review a case is not a decision on the merits and does not mean the court approves the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals’ decision. It is merely a determination by the court, which exercises tight control over its docket, not to review the case. Hypothesizing a rationale, it’s worth noting that plaintiff Evans has not suffered a final dismissal of her case, having been allowed by the 11th Circuit to file an amended complaint focusing on sex stereotyping instead of sexual orientation discrimination, so she can still have her day in court. In the context of her claim, then, there is no pressing need for the court to resolve the circuit split.

It may also be significant that Georgia Regional Hospital, whom Evans is suing, did not even appear before the 11th Circuit to argue its side of the case and initially did not file papers opposing Lambda Legal’s petition. The Supreme Court Clerk’s Office distributed the Lambda petition and some amicus briefs supporting it to the justices in anticipation of a conference they were to hold on October 27. The hospital’s lack of a response evidently sparked concern from some of the justices, who directed the clerk to ask it to file a response, which was filed by Georgia’s attorney general on behalf of the public hospital on November 9. The case was then put on the agenda for the court’s December 8 conference, at which the decision was made to deny review. The state’s filing argued, among other things, that the hospital had not been properly served with the complaint that initiated the lawsuit. Those kinds of procedural issues sometimes deter the court from taking up a case.

Whatever its reasoning, the court has put off deciding this issue, most likely for the remainder of the current term. The last argument day on the Court’s calendar is April 25, and the last day for announcing decisions is June 25. Even if the Second Circuit promptly issues a decision in the Zarda case, the losing party would have a few months to file a petition for Supreme Court review, followed by a month for the winner to file its response. Even if the court then grants review in that case, the filing of briefs on the merits and amicus briefs would likely force the case too late into the current term to be argued in front of the court before next year’s term that begins in October 2018.

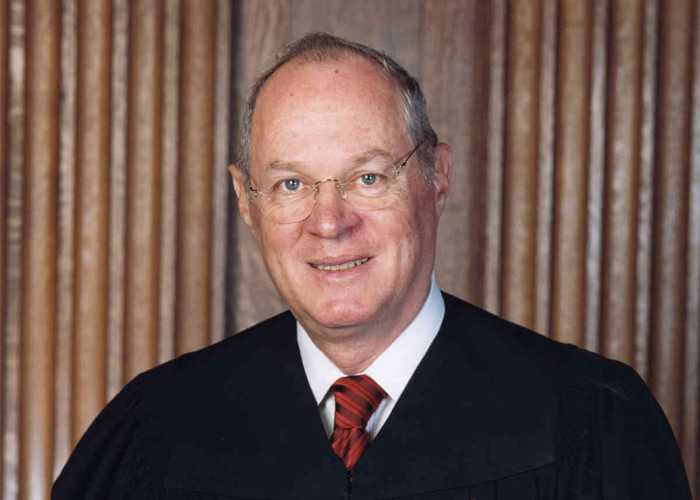

Unfortunately, that raises the question of who will be on the court at the time this issue makes it there. Rumors of retirements are rife, and they center on the oldest justices, pro-LGBTQ Ruth Bader Ginsburg as well as conservative but generally pro-gay Anthony Kennedy, who wrote the majority opinions in the four major gay rights wins the high court has decided since 1996. If President Donald Trump gets to nominate successors to either of them, the court’s receptivity to gay rights arguments is likely to be adversely affected as the example of Justice Neil Gorsuch has already made abundantly clear.