Depicting the progeny of villains to disprove art’s mythology

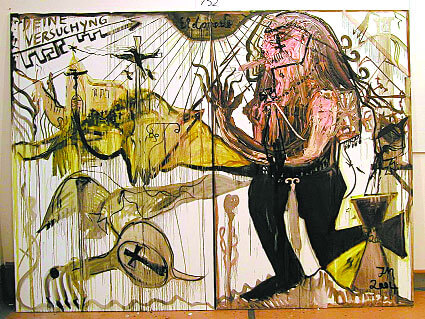

Oil on canvas. Large and medium-size paintings. The color is energized, yet more akin to the brown and yellow hues of old prints, or comic books, than the lurid candy shell tones of much contemporary painting.

Jonathan Meese, in “Dr. No’s Son,” continues his painterly deployment of his narratives. Meese has previously engaged his paintings with historical subjects: Nero, Imhotep, Caligula, Stalin, Mussolini, Hitler. In his current exhibition, Meese includes references to Echnaton, the Egyptian pharoah who first introduced monotheism, and El Dorado, the lost city of gold.

To Meese, history is presented as “straight from the tube,” like much of the paint in his works. History signifies not so much any independent reality as the mythology of nations and ruling powers. Similarly, Meese’s thematic examination of Dr. No (James Bond’s nemesis) establishes a concept of canned mythology. Meese’s super villain aesthetic places his work outside the assumptions and lessons of Pop Culture, as engineered by giant corporations. Meese’s narrative is more concerned with the anger of Dr. No and his soldiers than with the smooth antics of Bond.

Another exposition that runs through Meese’s gnarled storyboards relates to the artist’s personal and creative positioning. Just as history and culture present false narratives, so too does Art present a false narrative. Meese, who creeps into his own compositions by way of collaged photographs, is unwilling to seriously engage in notions of individual “greatness,” a notion at the very crux of the historical and cultural inanities that Meese satirizes. He is pictured, in a comic book-like catalogue of the show, as the quintessential art world egoist: camera at worm’s eye view, artist with prerequisite mask in hand.

A super villain? A tragic mastermind of dastardly plots that will surely be thwarted, reduced to comedy?

Why, certainly.