To understand the astonishing power and gripping drama of “Sunset Blvd.,” now on Broadway, it might be helpful to look back at the German expressionistic cinema of the 1920s. The stark black-and-white, the over-close, oversized projections, the relentless use of light and shadow, and, of course, the mannered performances, all create a haunting world where the faded star Norma Desmond is trapped between a tragic reality and her delusions.

Or perhaps you don’t need to think about any of that at all. The production stands on its own as powerful and visceral, stripped down to its essence as a raw tragedy of ambition and fame. This is not so much a revival of the 1993 musical, based on the 1950 movie of the same name, as it is a full-scale reimagining of the material.

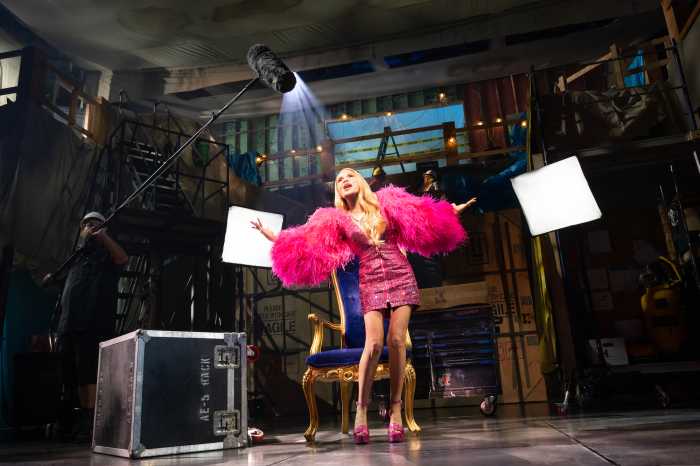

Director Jamie Lloyd has mounted the show on a largely bare stage, dominated by a movie screen where images of what’s going on below often dwarf the performers. Handheld cameras follow the actors (Ivo Van Hove used the same device in “Network” as did Simon Stone in the Met’s new “Lucia di Lammermoor.”) The enormous scale of the movies juxtaposed against the characters’ little lives below is a potent metaphor for the conflict between the supposed glamor of stardom in our culture and the banality and gritty darkness of real life. It’s timely as well, for in our world where personal value can be measured by presence on social media, it’s the fame — and the desperate desire to keep it — that is the paramount concern. Whether it’s Norma’s fan mail or likes on TikTok, the constant need for external validation is a mania.

The story is fairly simple. As the lights come up, Joe Gillis emerges from a body bag and promises to tell the story of how he got there. A failing writer, he ends up in the home of silent movie star Norma Desmond, now largely forgotten and living alone with her servant Max. Norma asks Joe to help her write a script about Salome for her comeback — a word she hates. Joe becomes entwined with Norma, a kept man, and Norma grow increasingly jealous and deranged as her script is rejected and Joe falls in love with fellow writer Betty Schaefer. Furious and jealous, Norma shoots Joe — and we’re back to the body bag.

The plot is overblown and somewhat nonsensical, but that doesn’t matter in the least. As conceived by composer Andrew Lloyd Weber with book writers Don Black and Christopher Hampton, this is really an opera — and no one asks opera plots to make sense, generally. The nearly sung-through piece comprises recitative and arias, and one of the advantages of Lloyd’s stripped-down production is that the music moves to the forefront, and this score is more complex and intelligent than it’s often been considered.

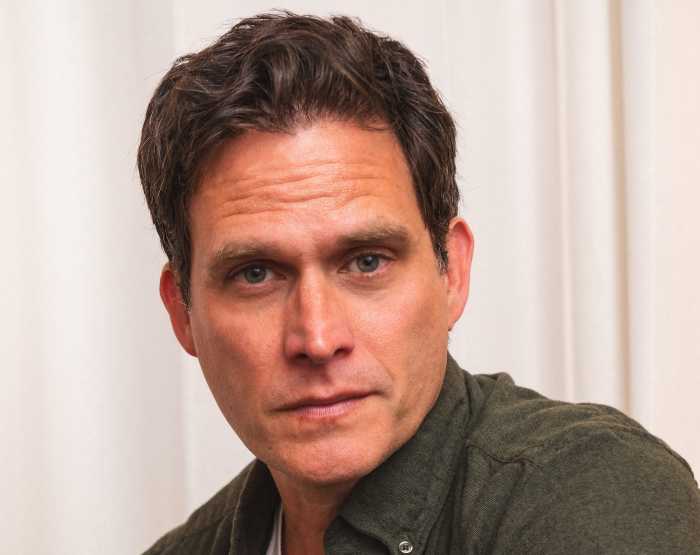

As a director, Lloyd has leaned into the grandeur (and the grand guignol) of the piece’s operatic scale, eliciting marvelously oversized performances from his incredible cast. The four principals have been brought over from the London production. David Thaxton as Max von Mayerling has a magnificent and powerful baritone. Max was Norma’s first director (when she was 17) and has devoted his life to supporting her delusions — and protecting the monster he created. Grace Hodgett Young as Betty, the writer Joe falls in love with as they work on a project together, is splendid. She has a strong voice, and Betty is the conscience of the piece, hopeful for her future and horrified at what Norma, and by extension Joe, become in their hunger for success. Tom Francis as Joe is sensational. He has a powerful voice and, while superficially charming, he plays the character’s dark cynicism beautifully.

The show, however, belongs to Nicole Sherzinger as Norma. She approaches the role with a ferocity and feral abandon that shockingly convey her lust for fame; she has nothing else. Even as her grip on sanity becomes more tenuous, she burns, sometimes coquettish, others rampaging. Sherzinger’s astounding voice and spectacular interpretation stop the show once in each act. Her two arias “With One Look” and “As If We Never Said Goodbye” provoked ovations that stopped the show. Sherzinger has an uncanny way of holding the audience in her hand while horrifying them with the character’s psychosis. She has elevated Norma to the iconic level of the operatic Medea, Lady Macbeth, or the Queen of the Night.

When “Sunset Boulevard” opened in 1993, it was a time of excess and overstuffed musicals where staircases, helicopters, and chandeliers dazzled audiences. Today, “Sunset Blvd.” (note the foreshortening of the title) is harder, harsher, anti-romantic. The starkness of the black-and-white world, thanks to designers Soutra Gilmour (set and costumes) and Jack Knowles (lights), is unabashedly cynical, but the production is pure theatrical genius.

Sunset Blvd. | St. James Theatre | 246 West 44th Street | Tues, Thurs 7 p.m.; Weds, Fri, Sat 8 p.m; Weds, Sat 2 p.m.; Sun 3 p.m. | $59-$450 and up here.