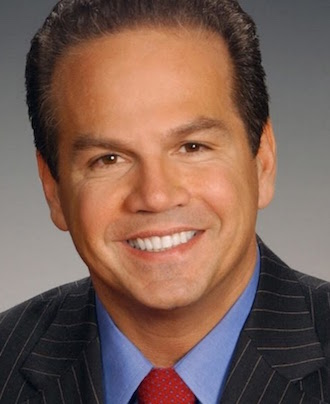

Steve-Shlomo Ashkinazy.

As the 1970s turned into the ‘80s, many Jews experienced a spiritual awakening that brought them closer to the pietistic ways of their grandparents and reinvigorated the Jewish identity. Steve Ashkinazy felt the call and went to Jerusalem for a year.

He returned in 1983, Orthodox but with a difference. He had reconciled his religion with his gayness. Others might disagree, but he knew in his heart his gay life could be pious. Reaching this conclusion was not a surprise to Ashkinazy. In fact, it was perhaps inescapable.

Steve-Shlomo Ashkinazy, as he became known, wasn’t born to the manor but to gay liberation. He came of age in the aftermath of Stonewall and the organized effort to toss off a history of homophobia.

Longtime gay activist applies “bottom up” organizing to challenge Orthodox Jewish dogma

“He has done a lot of front row change work,” said Miryam Kabakov, an activist who works closely with Ashkinazy.

When he began classes toward a social work degree in 1973, he was the first openly gay student in his program and the first to do his fieldwork in a gay setting. He was also the first principal of the Harvey Milk High School and a founding member of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, the nation’s pioneer LGBT lobbying organization.

Ashkinazy worked to counter anti-gay policies in the city’s foster care system and, as a founding board member at the LGBT Community Center, played a critical role in getting the city to agree to a sale of the building it owned on West 13th Street that became the Center’s home. Many of his fellow board members were bitterly opposed to Mayor Ed Koch, whose support was necessary for the sale to go forward. Ashkinazy’s diplomatic skills helped Koch overcome initial reluctance and okay selling off the former high school.

Ashkinazy brings a calm demeanor to his current project reconciling Orthodox Jews and their LGBT coreligionists. His efforts are part of a growing movement within the Orthodox community, and while they haven’t reached the tipping point achieved by the secular gay movement, Ashkinazy and his allies are making steady progress.

He credits the success to date to the central role played by simply coming out. Rather than confronting doctrinal differences, Ashkinazy encourages people to tell their stories. He calls this approach “bottom up” organizing — creating a sense of group solidarity before appointing leaders and seeking institutional changes.

Ashkinazy wears his yarmulke to gay events and is frequently approached by other Jews troubled by the hostility displayed by the Orthodox. The simple gesture of being openly religious, then, is a path to dialogue.

The push to reconcile gay orientation and ties to a traditional religious community is becoming common in the United States. In 2010, Matthew Vines left Harvard after two years of study to persuade evangelicals that their anti-gay interpretation of Leviticus is mistaken. The Bible, he argues, never condemns a loving, committed homosexual relationship. Vines and Ashkinazy share the conviction that their religions are open to moral and compassionate appeals.

Ashkinazy’s chosen vehicle is “the story” — public narratives told by LGBT Jews about growing up in a hostile environment. One man who participated in this storytelling recounted wearing a colorful vest for his high school graduation picture only to be told he was dressed inappropriately and ordered home by the rabbi. This humdrum summary of that episode doesn’t capture the powerful impact of watching the man retell the story years later as he recalls how carefully he dressed for graduation photo day. His story and others are best understood when told by those who lived them. For that, visit youtube.com/watch?v=ytzzq9rwhQA.

Compelling video narratives about Orthodox gays, in fact, preceded the advent of YouTube. Ashkinazy was among those featured in Sandi Simcha Dubowski’s 2001 documentary “Trembling before G-d.” which challenged and countered dogmatic rejection of LGBT lives by having people tell their own stories.

“It was successful,” Ashkinazy said of the film, “because it didn’t propose solutions but identified a problem.”

Steve-Shlomo Ashkinazy with Mayor Ed Koch in 1985.

In 2010, Eshelonline.org was founded to create a web-based community providing support for LGBT Jews living in Orthodox communities. Given the risks of ostracism, the Internet serves as a convenient and safe way for people to meet. Eshel also sponsors retreats, the next one taking place the weekend of August 9 in the Wisconsin Dells. The group facilitated the formulation of a statement of principles for educators and rabbis — with more than 200 signers — that urges the embrace of Jews with same-sex orientations “as full members of the synagogue and school community.”

Another recent event pointed up the powerful potential within the movement. Orthodox parents with LGBT children, who were long isolated from others going through the same experience, met for the first time.

“They felt they were in the closet,” Ashkinazy said.

They couldn’t tell their rabbi for fear their children would be ejected from the congregation and had no way to meet other parents. The gathering was marked by shocks of recognition; two brothers were surprised to run into each other, unaware the other also had a gay child. Giving LGBT Orthodox Jews and their parents a chance to forge broader bonds bodes well for change in this traditional religious community.

For 40 years, Shlomo-Steve Ashkinazy has actively pushed for a city that is welcoming to its LGBT residents.

“His ability to persist is an amazing gift,” said political scientist Ken Sherrill. “Most activists burn out, and he doesn’t.”

Miryam Kabakov, Eshel’s executive director, attributes Ashkinazy’s success to the fact that his work “hasn’t been about him. He is open and committed. He makes change in this lovely way.”

But it would be a mistake to say Ashkinazy makes progress only by employing a soft touch. In 1982, he won a police brutality lawsuit for injuries suffered during a demonstration against the filming of William Friedkin’s movie “Cruising.” Today, he sits on the LGBT Advisory Board to Police Commissioner Ray Kelly.