“On A Clear Day You Can See Forever” is a notoriously difficult musical. With a clumsy book and a very mixed score, were it not for Barbra Streisand in the 1970 movie (also a dud), it might be completely forgotten. The original 1965 production did run 280 performances, though the 2011 revival didn’t even reach one-third that number. Still, several of the songs have become enduring cabaret favorites, though others are not so great. So, it seemed like quite the risk for the Irish Repertory Theatre — I still can’t figure out what’s “Irish” about this show — to tackle this particularly problematic piece.

Well, the risk paid off handsomely. Adaptor and director Charlotte Moore has wrestled with the book — and won — cut at least two of the more idiotic songs, and mounted a thoroughly delightful production with a lovely cast and simply glorious singing. She has turned “On A Clear Day” into an intimate chamber musical that fits easily into the small stage at Irish Rep.

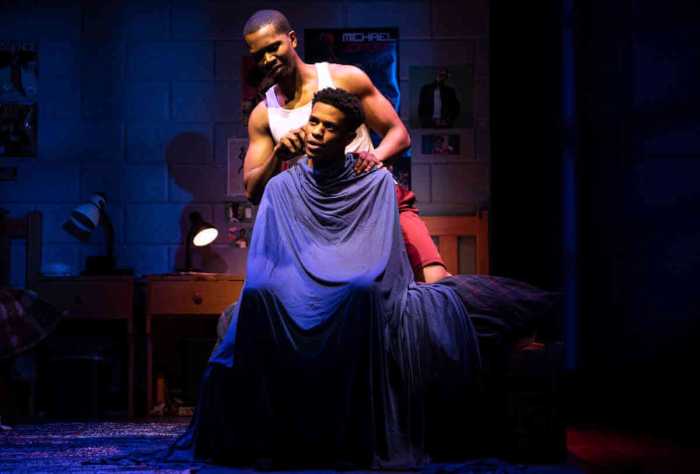

The plot concerns Daisy Gamble who has ESP and can make flowers grow. When Dr. Mark Bruckner hypnotizes her, to help Daisy stop smoking, he discovers that in the 17th century she was Melinda Wells. Reincarnation is real! And we’re off bouncing back and forth between the centuries. Mark falls in love with Daisy. Daisy thinks Mark only loves Melinda, and the time-traveling triangle becomes messy for a while, but it all works out in the end, of course, because Daisy finds herself as a happily, soon-to-be wife. Hey, don’t judge — it’s a musical. From 1965.

Director Moore and choreographer Barry McNabb keep the show moving. It’s a brisk and breezy two hours. Music director John Bell does a great job with the pared-down orchestrations. The ensemble is sensational. Stephen Bogardus as Dr. Bruckner is excellent, and you should see this for no other reason than to hear John Cudia as Edward Montcrief, Melinda’s suitor back in the day. His tenor is sublime. Melissa Errico is Daisy, and she is over-the-top terrific, combining the clear, bell-like soprano of a classic leading lady with outstanding comic chops and impeccable timing. Daisy is a loveable kook in the vein of Gittle Mosca from “Seesaw” or Flora from “Flora, The Red Menace.” In short, she’s a type, but Errico makes her appealing and, yes, loveable.

Moore and her company have done more than just create a delicious production. I’m willing to bet that this will be the version of this show done from now on. That much is clear as day.

Passion and politics go hand-in-hand in “Conflict,” Miles Malleson’s 1925 play now getting a flat-out wonderful revival from the Mint Theater. The play is best described as a drawing room comedy with a sense of purpose, a little lighter than Shaw but no less earnest. Set in London, the plot concerns two school friends who stand for Parliament from the same district. Sir Ronald is a strict conservative, Tory, while his erstwhile chum Tom Smith is a Socialist. Caught between them is Lady Dare Bellingdon.

Dare, as she’s known, never really questioned her politics or her life for that matter. She’s the stereotypical woman between the World Wars, looking to strike out on her own and have an adventure of an indeterminate nature. But when she meets Tom and is exposed to his politics, she finds a voice and a point of view that is new to her and threatening to Ronald and her father, Lord Bellingdon. She may well have found the adventure she is looking for.

The script has plenty of room for political talk, but the characters are so well drawn that it feels natural. We know that this all takes place a very long time ago because one of the key plot points turns on ensuring that the competitors stick to the issues and not descend into personal attacks.

The company is outstanding under the clear-eyed direction of Jenn Thompson. Henry Clarke plays Sir Ronald as a bit of a disconnected prig. He’s quite charming, nonetheless. Jeremy Beck is fiery as Tom, who became a Socialist after experiencing first-hand the privations of being down and out in the post-war years. The contrast between Tom and Ronald is both stark and subtle, which allows both men to be sympathetic, though there can be no question that the playwright’s sympathies are with Tom. Jessie Shelton gives a bright and heartfelt performance as Dare, and Graeme Malcolm is perfectly cast as the older aristocrat Lord Bellingdon.

The lovely, detailed set is by John McDermott, and the period costumes are by Martha Hally. As always, what the Mint can do with an Off-Broadway budget never ceases to impress.

This is the second Malleson play the Mint has presented. Last year, “Unfaithfully Yours” approached the then-controversial concept of fidelity and an open marriage. Malleson’s forthright takes on sex and politics are rational and well-considered. This is theater for adults — and the only place you’ll see a good, clean political fight these days.

Satire can be an unwieldy form. Largely rhetorical, it sits somewhere between comedy and social criticism. When it’s done extremely well, you get a Jonathan Swift, Mark Twain, or the comic strip “Doonesbury.” Satire is the wit’s favorite tool for poking fun at institutions, belief systems, or the follies of humanity and revels in exaggeration, silliness, and sarcasm. Yet because it trades heavily in implication, satire also has a short shelf life. A contemporary audience, for example, would have no idea which Athenian nobles Aristophanes was lampooning, though his audiences did.

Religion has been a fertile inspiration for satire for centuries, partially because it could deliver indirect attacks on the Church in times when direct questioning could land one in jail, or worse. Chaucer and his “Canterbury Tales” are still the benchmark for this form. Given the fervor of the Evangelical Church today in the US, criticism can raise the ire of the faithful easily, though a sharp retort on Twitter is nowhere near as lethal as a stint in the Tower.

“The Saintliness of Margery Kempe,” now at The Duke, wades into our fractious culture with a biting satire of self-aggrandizement, the quest for celebrity, grasping selfishness, and corrupt belief systems. Though the original play is 60 years old, these themes are, woefully, very relevant. The plot concerns Margery, a bored housewife who yearns to be a star. Given that she lives in the 14th century and has no access to Instagram, her only recourse, as she sees it, is to become a saint, which she sets out to do, in the process wreaking havoc on her family, the traveling companions she forces herself on, and the entire city of Jerusalem, claiming the special privileges that come with being chosen by God. Reason and rationality cannot reach her. Her prevailing sentiment, which has a hauntingly contemporary echo, is that when you’re a saint they let you do it. Indeed they do, as Margery is highly adept at making people fear God, and, despite several setbacks, her quest for the Medieval equivalent of ratings will not be thwarted.

This play also points out satire’s shortcomings. For one, it’s too long. Plot points are overly labored, undermining the picaresque nature of the plot and blunting its bite. Clocking in at over two hours, the play could lose 30 minutes and the intermission and be more successful. As directed by Austin Pendleton, the characters often lack affect or speak with a contemporary cadence. Listening to actors in period costumes self-consciously sounding like teens at a modern mall is now so overused it’s become one tired trope.

Andrus Nichols plays Margery as a woman chasing fame with Khardashian-esque ferocity. There’s not much nuance in the role or the performance, but Nichols has a wonderful presence and that works well for her in this. The rest of the cast switch roles, sometimes with dizzying speed. Not much is demanded of them, and they deliver.

For this to have worked as satire, though, the audience should be sitting there saying, “I see what you did there. Go get ‘em.” Instead, the response was a much more blasé, “I get it. Can I go home now?”

____

ON A CLEAR DAY YOU CAN SEE FOREVER | Irish Repertory Theatre, 132 W. 22nd St. | Through Sep. 6: Wed., Fri.-Sat. at 8 p.m.; Thu. at 7 p.m.; Wed., Sat.-Sun. at 3 p.m. | $50-$70 at web.ovationtix.com or 866-811-4111 | Two hrs., with intermission

CONFLICT | Mint Theater Company at the Beckett Theatre, 410 W. 42nd St. | Through Jul. 21: Tue-Sat at 7:30 p.m.; Sat.-Sun. at 2 p.m. | $65 at telecharge.com or 212-239-4200 | Two hrs., 10 mins., with intermission

THE SAINTLINESS OF MARGERY KEMPE | The Duke on 42nd Street, 229 W. 42nd St. | Through Aug. 26: Tue.-Thu. at 7:30 p.m.; Fri, Sat 8 p.m.; Sun. at 7 p.m.; Sat.-Sun. at 2:30 p.m. | $55-$92 at tickets.dukeon42.org or 646-223-3010 | Two hrs., 20 mins., with intermission