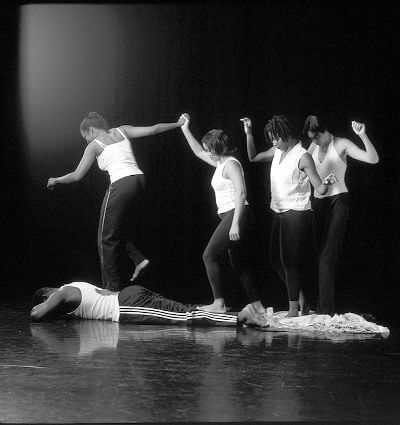

Wilson, Douglas, and Umfolosi celebrate individualism and unity

“Black Burlesque (re-visited),” a joint project of three artist groups from the African Diaspora, celebrates song and dance traditions that have migrated across space, time, and culture. The work was developed over years of experimentation and exchange between New York-based choreographer Reggie Wilson and his Fist and Heel Performance Group, Trinidadian choreographer Noble Douglas and her company, and Thomeki Dube and other members of the Zimbabwean a cappella group, Black Umfolosi.

The performance took place at the Dance Theater Workshop October 22 through November 1.

Southern Africa, the West Indies, and America come together in this ambitious work that earnestly illustrates a shared ancestry through shared customs—clapping, stomping, singing, shouting. The work juxtaposes and integrates circle and line dances, gumboot dancing—a dance invented by South African miners—West Indian dance, ring shouts, and popular dance and music styles. Ritual practices intermingle with presentational entertainment. It is pastiche that in part one the dance is presented, for the most part, by the individual practitioners; in part two the people mix it up, and there is full unison.

The performance is backgrounded by Thabiso Phokompe’s large earth-tone fabric patchwork that shifts color beautifully with Tyler Micoleau’s lighting changes. Two disco balls hang at opposite corners of the stage. House music opens the piece, the disco balls in effect, but only feet are visible in a low shaft of light, moving in a circle. Side strutting, step dancing to old time blues comes next. Greetings recycle in a rotating formation. Everything feels familiar if not ritualistic.

Recorded music gives way to singing performers. Mr. Wilson appears for the first time, shout-singing in a highly stylized fashion, as spine tingling and spiritually commanding as a call to prayer.

Much of the choreography is like moving musical sculptures, with the dancers dressed handsomely in Adrienne McDonald’s costumes, a collage of tie-dye, mud cloth, and other African textiles. The rhythmic boot stomping, body clapping miner dance is performed first as a trio, and it is impossible not to think of step dancing or even tap. Modern dance phrases, all swinging straight arms and straight legs, frame the action. In a quieter sequence that has a ceremonial feeling, three women walk across three white dresses laid out one by one in a circular pattern. Caribbean dance music and emblematic hip-shaking forward movement gets a turn, and then the group reforms into a circle.

An abrupt music change transports the action back to the beginning. A barrage of super fast lighting changes repeats several times. Couples step together. The white dresses reappear in an almost actionless double duet, where wiggling toes seem to say a lot. Rhetta Aleong shimmies across the stage toward a small group playing percussion and singing, as if she is drawn involuntarily by the music.

Part two begins with the ensemble sitting on the floor in a semi-circle with their legs out in front of them, singing and gently swaying. Now black outs are used for transitions, and the next scene starts with a dramatic phrase that evokes working in the fields. With their bodies hanging over and lined up front to back, the group moves across stage stomping and swinging down one arm as they step.

Maxwell’s music works well with a step dance duet and quartet, and from this point, the integration of the various styles pours into the mix. Four dancers continue to step dance while four others move with the weight and focus of modern dance.

Next comes a trio of West Indian dancing. The individuals that were introduced earlier within their own frames of reference are now more obviously part of a larger group. When the cast (less Wilson) does the miner dance together, it is a literally resounding experience––the heaviest tap dance ever, in more ways than one. Movement that includes jumping, spinning, twisting, singing, and rejoicing upwards fittingly concludes the work.