“O, wonderful, wonderful, and most wonderful.” That line of joy and awe from Shakespeare’s “As You Like It” is perhaps the best expression of feeling at being back in Central Park for Shakespeare in the Park, one of the quintessential New York theater experiences.

Closed and refurbished over the past 18 months, and with a reported investment of $85 million, the Delacorte is back. The theater will look largely familiar to regular fans with the great expanse of a Manhattan night smiling down at the revels below, as it has for 64 years. The Delacorte has been a home to world-class stars — and raccoons — and memorable productions, and, as with many things, in its return is the realization of how much it was missed, not just for the shows but for the role the Public Theater takes in demonstrating how theater builds community, which, sadly, has never been more important.

To inaugurate the return of this beloved institution, the Public has mounted a colorful and buoyant new production of one of Shakespeare’s most dependable comedies, “Twelfth Night.” Director Saheem Ali has crafted a fast-paced production that is heavy on gags and often quite lyrical, but in shaving it down to a rapid-fire two hours without intermission, despite all the jollity, something is lost as well.

The convoluted plot concerns Viola, who, shipwrecked and separated from her twin brother Sebastian, lands in Illyria, where, disguised as the boy Cesario, she goes to serve the local count Orsino. Orsino, for his part, is in love with the countess Olivia, who will have none of him. Orsino sends Cesario/Viola to plead his case, whereupon Olivia falls madly in love with the boy, not the count. Cesario/Viola, however, is madly in love with Orsino but can’t reveal that he is a girl. Complications ensue, particularly when the not-drowned Sebastian shows up. Meanwhile, a poor nobleman, Andrew Aguecheek, who has come to woo Olivia for himself, is rejected and falls in love with Olivia’s cousin, the degenerate Sir Toby Belch. Toby and Andrew, whose carousing is excessive, run afoul of Olivia’s steward, Malvolio, and along with Olivia’s maid Maria, hatch a plot to get even with him. Chaos ensues, but of course being a romantic comedy, it all works out in the end, at least for the romantic couples.

While there are plenty of laughs and many opportunities to be charmed, director Ali has often downplayed the more mordant elements of the romantic comedy. Beneath the antic merriment, there is an undercurrent of sadness at the transitory nature of life and inevitable loss and the dark disquiet of unrequited love. In racing through the truncated text, it feels like Ali doesn’t fully trust the material, and the play is ultimately shortchanged of some of its more human depth and nuance in favor of more facile laughs.

That is not to say that there aren’t many pleasures to be had. The comedy often works, even when it feels forced onto the material, such as when Aguecheek and Toby are cavorting in a hot tub with blasting music and blow. There are some wonderful touches, such as having Viola speak in Swahili, which is both beautifully lyrical and shows she is not from Illyria — a stranger in a strange land — which is its own romantic theme. However, one of the larger questions of this production is why Cesario/Viola would fall in love with Orsino. Traditionally, Orsino is played as a lovesick romantic, subject to Olivia’s simple dislike of him. Here, Orsino is a bro who is unquestionably supported by a gang of sycophants and who seem to think Olivia owes him just ’cause he’s so awesome. It may be a timely commentary, but it weakens the play’s mordant observations on the fickleness of love.

Set designer Maruti Evans has left the stage largely bare, with the exception of giant letters upstage that spell out “What You Will,” the play’s subtitle, which sometimes seems like a challenge to the audience to make sense of all the goings on.

Even with these cavils, the cast is a joy to watch. Lupita Nyong’o is Viola/Cesario, and she is consistently charming, particularly as she explores the awkwardness of her own nature and the challenges of her assumed gender. She manages the poetry and the comedy with ease throughout. Her real-life brother, Junior Nyong’o, is an appealing — and rightly befuddled — Sebastian.

Peter Dinklage fully embraces the stiff egoism of Malvolio, who is secretly in love with Olivia, who is tripped up by his own suppressed ego by Toby and Andrew. He manages both to be silly and heartbreaking when the mean-spirited trick is revealed. Olivia at one point tells him, “You are sick of self-love,” and his bad usage is the direct result of that.

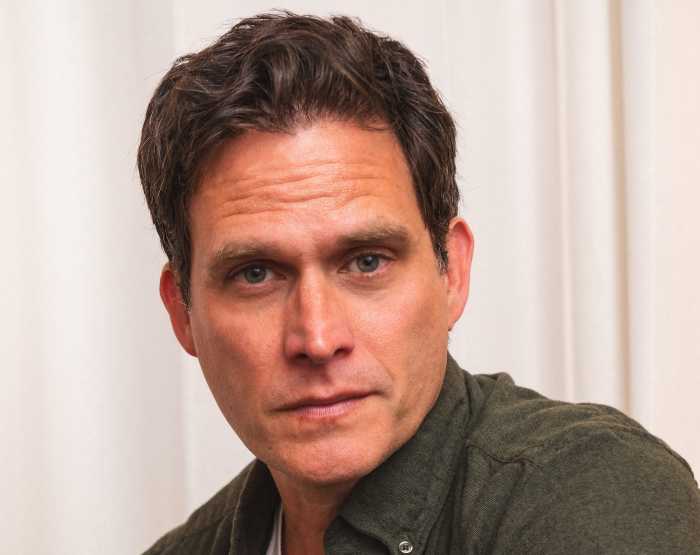

As the comics, John Ellison Conlee as Toby and Jesse Tyler Ferguson as Andrew deliver the gags, but director Ali has skirted around the heart, particularly of Andrew. Ferguson is one of our most dependable comic actors today, and one only wishes he’d been given the chance to show the subtext of sadness in Andrew, who like the other characters who, as Benedick reflects in “Much Ado About Nothing,” “suffers love” as much as experiencing it.

Moses Sumney is excellent as Feste, Olivia’s fool, but the part has been cut down so that the songs that underscore the realizations of the passing of time and life are robbed of their ability to provide the darker counterpoint to human silliness.

Sandra Oh is a dazzling Olivia, both manic and heartfelt, mourning the dead brother that has prompted her to avoid all romantic involvement but awakened to passion in a moment when she sees Cesario/Viola. She is a perfect embodiment of how love can make fools of us all.

The production ends, as Shakespeare often does, with a dance. In this case, there is a not-so-subtle comment that expresses a theme the Bard probably did not consider: Gender merely is a construct, and love will find its way.

We should all be happy that so much love has found its way back to Central Park.